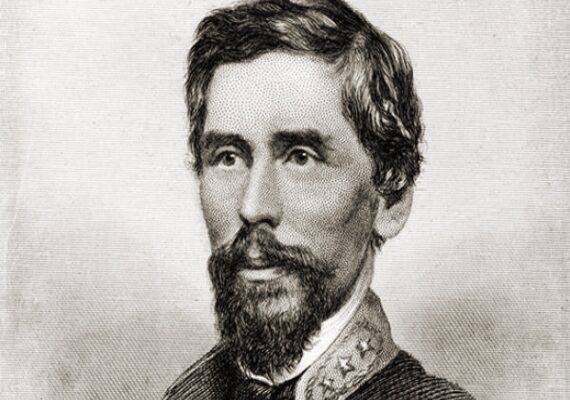

The following is a four-part series on the life of Major General Patrick Cleburne, C.S.A. It derives heavily from two sources, “Cleburne and His Command,” by Captain Irving A. Buck, C.S.A., (1908), and “Stonewall of the West: Patrick Cleburne & the Civil War,” by Professor Craig L. Symonds, Lieutenant U.S.N.R., (1997). For the sake of brevity in a blog article, citations will refer to last name and page reference.

Introduction

Iad siúd a fhaigheann bás ar son a muintire, ní fhaigheann siad bás ar chor ar bith [Those who die for their people never die at all] ~ extracted from an old Irish Story

For many reasons, Major General Patrick Cleburne speaks to me personally, nearly one-hundred-sixty years after his death. To begin, we are both of Irish extraction. Major-General Cleburne was born in the same county as my Irish grandfather, County Cork, also known as Ireland’s “Rebel County.” He was born approximately forty-five minutes from the birthplace of my distant cousin, Michael Collins. As such, there was no lineal reason for Cleburne to surrender his comforts and life to fight and die for the South. Most of his family settled in the North and served the Union army admirably, albeit undistinguishably. His younger half-brother, Christopher Cleburne, was the only other child in his family to emigrate to America and serve Dixie. He became a Captain in the Second Kentucky Calvary and was killed in action at the Battle of Cloyd’s Farm, Dublin, Virginia, May 1864, six months before Patrick Cleburne met his own terminal fate. What drove this Irishman to give everything he had to a South that he loved is crucial for me, as well.

I, too, was not born in the South. My Southern roots are thin, at best. I was raised most of my childhood in my Irish grandmother’s care in Ocala, Florida. Herself not Southern, the introduction of Southern culture was provided to me by my school-aged friends, teachers at Blessed Trinity, older male mentors, and then reinforced when I joined the Marine Corps at seventeen-years-old. The irony was that my Southern grandmother, Virginia, was never really in my life, so I did not learn from her that which endeared me so much to the South. Her family has been in Virginia since the middle of the 17th Century. She married a man, my American grandfather, whose mother was also from Virginia. He, too, had little to say about the South.

For those who doubt blood memory, I promised myself I would get a degree from the College of William & Mary the first time I visited that campus. I did just that, only to find out years later that I had ancestors who also attended the College of William & Mary dating back to the 18th and 19th Centuries – facts never before disclosed to me. Virginia will always be important to me in ways I may not even know.

My stepfather, a Yankee, with origin roots both in Plymouth and Jamestown, was most responsible for putting the South in perspective when I was young. As a Civil War buff, he was a great admirer of the Confederacy – both ideologically and militarily. His library was filled with nearly every biography available on Southern history and military leadership – from John C. Calhoun to Stonewall Jackson to Kirby Smith. “Many of the issues we face today are due to Lincoln’s invasion.” That was said in the late 1980s.

I made my way back to the South as soon as I could, after the Marine Corps, college, and graduate school. My wife hails from a multigenerational Southern family, rooted in Georgia and Alabama. Her ancestors fought for the Confederacy, primarily serving the 10th Alabama and the 14th Georgia Regiments. Our children are all born in the South. My home is in the South. Despite the strength of my Irish identity, the South is my great love. I assume Patrick Cleburne felt the same way.

Returning to the Major General, he and I share some similarities and some differences. Beyond being Irish, we were both young, enlisted infantryman. We both hated garrison life. He was raised an elite Anglo-Irish Anglican; I was raised a poor Irish-Catholic. We both found the Presbyterian faith later in life as having the closest theological grounding to our own sense of faith, while neither of us joined a Presbyterian church for similar reasons. He was incredibly shy. No one would ever accuse me of being shy. We are both tall, with dark hair and blue eyes, characteristics of our Irish DNA. One last similarity is this: both of us would sacrifice everything for the South – it is our home; his country Arkansas, my country Florida.

As I write this four-part series on Cleburne, I will touch upon various stages of the Major-General’s life. This first article will cover the making of Cleburne, from Irishman to Arkansas resident. Second, I will describe the making of a commander, including his rise in Arkansas politics and his failures at Shiloh that would profoundly mold Cleburne as a leader. The third installment will attempt to show Major-General Cleburne as the strategist, tactician, and warrior who would become the “Stonewall of the West.” Finally, I will cover the death of Cleburne, the controversies surrounding him, to include an obscure invitation by fellow Irish-Protestant and Cork-born General, the Union’s “Fighting Tom” Sweeny, to join in a Fenian “army” of Irish national liberation after the war.

One other element I hope to add to the study of Mr. Patrick Cleburne, the man, not the soldier, is one related to personal insight. Most American authors divorced from Irish culture likely cannot grasp the peculiar cultural paradigm of 19th Century Anglo-Irish elite society and the Protestant minority in the South of Ireland. Although I was raised Catholic, I had a Presbyterian father, and I was never raised to view Irish-Protestants as “less” or “enemies.” Rather, like most things cultural, there is nuance and balance that history rarely pierces. This is the tragic limitation of studying the works of the past that fail to convey emotion. I hope to give context to Cleburne’s unique cultural upbringing which likely played a key role in his devotion to his beloved South.

Cork, Ireland

Patrick Ronayne Cleburne was born the day before St, Patrick’s Day, March 16, 1828, to Dr. Joseph and Mary Ann Cleburne, formerly Ronayne. Cleburne was born into a unique class of Ireland – that of the Anglo-Irish Anglican elite social station. Whereas there appears to be no in-depth study as to Patrick Cleburne’s roots, his mother’s name is an Anglicized version of O’Ronan, a name from Cork dating well back to the 12th Century. The last name “Cleburne” derives from Cumbria, a county in Northwest England, on the Scottish border. The name is interesting, because it is Anglo-Saxon versus Anglo-Norman. In Ireland, older Norman families had settled shortly after their successful invasion of Ireland in 1171 and largely intermixed with the original Gaelic inhabitants, eventually becoming “more Irish than the Irish themselves.” Consequently, it can be deduced that Patrick Cleburne hailed from a family of relatively recent Anglo origins on his paternal side (within the preceding 200 years) and high born, Gaelic stock that converted to the Church of Ireland (Anglicanism) at some point on his mother’s side.

Cleburne’s maternal grandfather, Patrick Ronayne, for whom he was named (Buck P.6), held the title of “Esquire.” which unlike the American affiliation with a legal background, was a title conferred to honored men in the 18th and 19th Century United Kingdom. As a rank above “Gentleman,” but below “Knight,” it was a rank reserved for candidates of knighthood, usually due to some exemplary service on behalf of the Crown. Whereas we do not know exactly what his grandfather did to earn this title, it would indicate Cleburne’s mother was the higher of the two in terms of social status. In essence, this would mean Cleburne was born into a family not quite wealthy enough to enjoy all of the monetary privileges of title or landed gentry class (as with other Anglo-Irish), but an economic and social station far higher than the repressed Catholics around whom he would have found himself. In fact, his mother came to the union with a six-hundred-pound sterling dowry (Symonds P.10), a substantial sum at the time.

As a graduate of the University of London and the Royal College of Surgery in Dublin, his father was clearly an educated man who enjoyed a noble profession, but one that was not nearly the wealth generator that it would become in the 20th Century. In effect, Cleburne was born to a comfortable household of good station, on the margins of aristocracy, but not actually aristocratic. He would be best described as very high middle-class.

A clue as to the origins of Patrick Cleburne’s sense of justice and honor were the actions of his father while Patrick was not yet one. Catholic emancipation was a hot button topic in Ireland in the early-1800s. The issue divided the Anglo-Irish community, with many believing the elevation of Irish-Catholics to equal status would lead to the displacement of the Anglo-Irish, while others believed that personal conscience was a fundamental right. Voting records of Joseph Cleburne indicate that he sided with the latter. Author Symonds writes “[Patrick Cleburne’s] father’s public declaration of sympathy for the cause of Catholic Emancipation suggests that while the Cleburne home was one of relative comfort and privilege, the family was at least sensitive, if not actively sympathetic, to the lot of the downtrodden and disenfranchised.” (Symonds P.12)

Further indications seem to reinforce this narrative. Whereas the Anglo-Irish were generally despised by many of the Catholics in the South of Ireland, Cork was especially a growing hotbed of discontent, the Cleburnes were generally well regarded. As a doctor, Joseph Cleburne apparently built a reputation of fair costs, sympathetic bartering, and care for even his poorest patients. When Patrick’s mother died in childbirth before he turned two years old, his father employed and later married a governess, Isabella Jane Stuart, who was more than half Joseph’s age. The family grew quickly, necessitating a larger home. When Dr. Cleburne secured a much larger home through a one-hundred-year lease, he was elevated to landed gentry, becoming an Esquire himself.

The process seems a bit awkward by American standards, but it gives insight into Patrick Cleburne’s early formation. Large landowners of Ireland were generally absentee members of the British aristocracy. They would effectively parcel their land and rent the land to members of the lower elite classes – these were called middlemen or the middle class. The middlemen would take the land and occupy the well apportioned homes while further leasing other portions of the land to poor tenant farmers. The tenant farmers would pay for their parcel of land back to the middleman in either pound sterling or equitable agricultural yields, and the middlemen would pay the absentee landowner. This effectively ensured that middlemen would live rent free and often earn enough to become comfortable. During economic hardships, with no abatement coming from the Crown regarding taxes, nor payment relief from the landowners, middlemen often resorted to harsh punishments for non-payment, including eviction and asset seizure. During the good times, this was rare; during times of a drought or a blight, eviction meant a death sentence – especially since British policy did not allow the Irish to eat that which they grew on their land (it was the property of the middlemen). This is what made the Potato Famine so brutal – the inability of the Irish to source other foods due to the long reach of Crown policy into the tenant-middleman-land owner relationship.

Joseph, however, did not do that. Rather, Dr. Cleburne sub-leased two parcels that provided for ninety-pounds of income to offset his two-hundred-thirty-pounds annual payment (Symonds P.13). The rest, however, he paid through his own meager agricultural crops and his medical practice. He neither took advantage of the poor tenant families nor profited from their exploitation. His request was considered fair. Unfortunately, for his family, and fortunately for Arkansas, this led to a family exodus at a later date.

As was customary of an Anglo-Irish son of means, Patrick Cleburne went to a boarding school led by an Anglican Reverend. His schooling, however, took place in Cork, Ireland, yet another indication that he was higher class than most in his area, but not economically elite enough to go to boarding school in England or Dublin. Still, young Patrick received a rigorous education. The Reverend William S. Spedding was a noted disciplinarian, very strict and reserved, imparting upon the young boys a certain sense of “terror.” (Buck P.8) Regrettably, Rev. Spedding focused on practical skills – mathematics, science, English language, decorum, history, etc. – and chose not to focus on Latin or Greek (Symonds P.15-17). This is something that would prove yet another misfortune for the family, but a benefit for Cleburne’s future home.

At age fifteen, Dr. Joseph Cleburne died, leaving a wife, eight children, and a massive rental payment. An orphan with family obligations, his older brother, William, left the elite Trinity University to manage the estate while Patrick chose to leave school to accept an apothecary apprenticeship (in some sense, a combination pharmacist-nurse). The apprenticeship was established with Dr. Thomas Justice, yet another indication of the universal respect held for the former Dr. Cleburne.

This effectively brought one man back into the home (William), saved the family any costs related to university expenses, and eliminated the need to feed another young man or pay for his continued education (Patrick). By 1845, William appears to have stabilized the estate and actually added productive land to the property (Symonds P.19-21) while Patrick did very well as an apprentice. In fact, Patrick did so well that his new mentor, Dr. Justice, allowed his seventeen-year-old apprentice perform house calls on his own. Soon, however, those house calls would increase in size and severity. In the winter of 1845, the first signs of the potato blight began to emerge in Ireland thanks to the crop swap, that provided the Irish with diseased potatoes originating from the United States, while the British took the good Irish yields for their own consumption and the needs of their military.

Throughout this time, the promising young apprentice studied and attempted to earn admission into Trinity College, like his older brother. Unlike his older brother, he sought to attend the prestigious Apothecaries’ Hall (essentially, the medical chemists school). Unfortunately, the strict examination required proficiency in Latin and Greek – skills that, as previously mentioned, were not taught by Rev. Spedding. Denied entry into the school on account of this weakness, “the sense of disgrace overwhelmed the boy” and Cleburne “immediately enlisted without communication with his friends and became a solider in the Forty-First Regiment of Infantry” (Buck P.8).

To enlist, Patrick Cleburne lied about his age when he was seventeen-years-old (Symonds P.21), a few weeks shy of his eighteenth birthday. Furthermore, so ashamed for his family name by his failure, Patrick listed his profession as “laborer” (Symonds P21). His stepmother, whom he adored, and his family did not find out about his enlistment or even his whereabouts for nearly a year-and-a-half. The only reason anyone learned of his enlistment was a fluke. A family friend, an Anglo-Irish officer in the 41st, told his stepmother while making a simple call to the family while traveling past their home on the way to his own, assumed the young boy told his family. This, too, became a sign of things to come, benefiting the Confederacy.

For his part, Cleburne was initially under the impression that the 41st Regiment would take him to Madras and he would serve the British Army in India. Unfortunately for Cleburne, the 41st was held at home at the last moment, due to the growing instability of that which would be called the Potato Famine. His tasks were largely relegated to evictions at the behest of middlemen, marching in force to show British dominance on Irish soil, and constant military training and drill for an inevitable deployment to the tropics. Speed, discipline, orders of alignment, battlefield commands – all of this was taught and according to all counts, well absorbed by the young Cleburne. In fact, Cleburne excelled so well, that in three years, at the age of twenty, he was elevated to a corporal in the British Army, a distinction for its time. Still, he hated the Army, and when he received his inheritance at the age of 21, he paid his way out of service (Symonds P.24).

An interesting foretelling of Cleburne’s military capacity came in the form of Captain Robert Pratt, the same officer who called on his stepmother and accidentally informed her of Cleburne’s whereabouts. Captain Pratt pleaded with Cleburne not to leave the Army and believed that Cleburne would undoubtedly get a commission in Her Majesty Queen Victoria’s military (Buck P.9). For an officer to take such a liking to an enlisted man in the stratified British Army meant something. However, it means even more when one learns that Captain Pratt would go-on to become British General Robert T. Pratt who would serve with distinction during the Crimean War, the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and later, the conquest of the Māori. In later years, General Pratt read of Major General Patrick Cleburne’s exploits on American soil.

Having purchased his freedom from enlistment, the family still had a small amount of inheritance saved, just as Ireland was effectively collapsing by the weight of the famine. The land became too difficult for William to manage, as failing crops and either emigration or death eliminated reliable Irish laborers. The children of Dr. Joseph Cleburne’s first marriage – William, Patrick, Anne, and Joseph – all left for America in 1849, hopeful to build a new life and send home the means to care for their loving stepmother. William was provided an introductory letter to a company in New Orleans (Buck P9; a job that fell through). The others would simply carve out their own path.

Unlike the mass of Irish that generally boarded ships bound for the bigger Eastern harbors, the Cleburne’s traveled in respectable quarters. Furthermore, they took a path that, until the mid-1850s, was generally less traveled by the Irish: New Orleans and the Mississippi River. William would eventually find work in Wisconsin, Patrick and his siblings worked in Ohio. As fate would have it, Patrick got a job at an apothecary and having done exceedingly well at his work, was provided an introductory letter by the former owner of a Helena, Arkansas apothecary in need of professional management. In just a few short months in Cincinnati, Ohio, Patrick Cleburne left for Helena, Arkansas, to meet Dr. Charles Nash and his business partner, Dr. Hector Grant (Symonds P.27-28).

Cleburne Arrives in Helena, Arkansas

Helena in 1850 was very much a Western town at the time of Cleburne’s arrival. It was also very new to both the settlers who were entering Helena nearly daily and Patrick Cleburne. For his part, Cleburne experienced some of the anti-Irish sentiment of the time, but not to the same degree that would have been experienced in Boston or New York in the 1850s. It would have been impossible for most Americans to distinguish between the poor rabble of masses entering New York’s Five Points from the elite Anglo-Irish, with the exception of manner, dignity, and customs Cleburne no doubt displayed as a gentleman. Still, he had a brogue and the name Patrick – “Paddy,” the subject of most mid-19th Century Irish jokes.

Symonds’ retells one incident in which Patrick came to learn Southern humor. Never having seen a watermelon before, Cleburne marveled at the size of the fruit. A young apprentice at the apothecary told Cleburne that the only way to eat watermelon was to cut it into pieces and boil it – which Patrick did. The apprentice continued the joke by telling Cleburne that the way to serve watermelon, after it was boiled, was to dish out the hot watermelon in bowls with spoons. When the doctors returned to the apothecary, Cleburne was proud to serve them bowls of boiled watermelon. The men could not hide their disgust and told Cleburne he was the butt of a joke. The apprentice ran out of the store laughing with Cleburne “hard on his heels” (Symonds P.29).

Embarrassing as that might be, Southerners, for their part, were not like the disengaged Yankees he had met in Cincinnati. In Ohio, Cleburne left work to eat and sleep in a boarding house with other poor Irish workers. In Helena, friendships were growing. While he would take occasional ribbing from his Southern colleagues, he was also quickly earning their trust as a man who was serious and hardworking. This contrast of acceptance would earn Cleburne’s love for the people and his admiration by them.

Within a year and a half of arriving to Helena, Dr. Grant indicated his desire to sell his share of the pharmacy. Heretofore, Cleburne operated the store like it was his own – grateful for the opportunity provided to him and desperate never to disappoint those who placed their trust in him. In fact, Cleburne appears to have had a driving fear of disappointing those who placed their faith and confidence in him – another facet that would mark him later as a military commander. Dr. Nash was so impressed with Cleburne that he implored Cleburne to buy Grant’s share of the business. He did so, with $350 and the remaining $1,150 (a total of $1,500) would be paid over twelve months (Symonds P.30). In effect, in 1852, Cleburne became a sweat-equity partner until he could pay off the balance of the loan, which according to all accounts, drove him to work even harder.

Soon, with ownership, hard work, good humor, and a dignified demeanor, Cleburne joined the Helena Masonic Lodge. He became a member of the Episcopal Church upon arrival. In both, he attended meetings and services regularly and rose through the social ranks of Helena Society. In 1853, Albert Pike conferred upon Cleburne “the sublime degree of Royal Arch Mason” (Symonds P.32). In less than four years, Patrick Cleburne went from a Corporal in Her Majesty’s Army to an established and successful citizen of Helena, Arkansas – and that was only the beginning. The South was now Cleburne’s home and Arkansas, not Ireland, was his country.

In the next installment, I will retell the incidents that led Cleburne from a respected citizen to a local leader, the formation of the 1st Arkansas (later renamed the 15th), and his early experiences as a commander for the Confederacy.

The son of a recent Irish immigrant and another with roots to Virginia since 1670. I love both my Irish and Southern Nations with a passion. Florida will always be my country. Dissident support here: Padraig Martin is Dixie on the Rocks (buymeacoffee.com)

Fascinating! I eagerly look forward to the next installment.

My ancestry also hale from Cork, Ireland. My great grandfather was a dentist. Unfortunately, I have yet to explore his history.

What a great read! Thank you.

“The good man leaves something for his childrens children.” Remember that verse? I’m sure someday there’ll be a lot of writings about Padraig Martin … CSA II’s first President and what a hero he was. His name will be common in every southern classroom.

People will say, “Imagine living back then!”