Readers of the first part of the 1871 essay continued below, will readily recall that our able author, Commodore Matthew Fontaine Maury, had gently carried us from the Revolutionary period of this country’s history, up to that moment in U.S. history at which an act of Congress known to history as the Missouri Compromise was introduced, debated and passed by both houses of that body, and signed into law by the President.

Our continuation of Maury’s essay here begins where we last left it. Namely, at that paragraph in his paper wherein our author begins to explain, with geographical acuity and mathematical precision, the extent to which the piece of legislation in question heavily favored the Northern states, and thereby and at length, played its decisive role in working the destruction of the balance of power which had previously existed between the two sections. It is at that juncture of our author’s paper and his history that we pick back up and offer, for your continued edification, Part II of III of:

A Vindication of Virginia and the South, By Commodore M. F. Maury

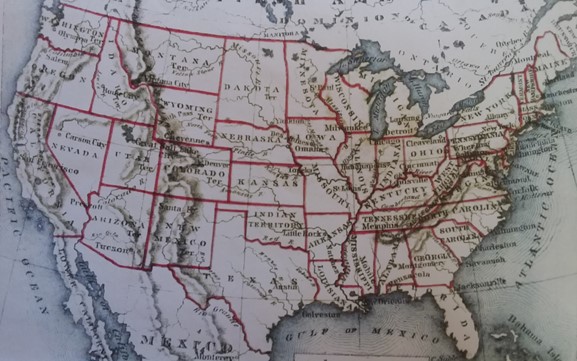

That posterity may fairly appreciate the extent of this exaction by the North, with the sacrifice made by the South to satisfy it, maintain the public faith and preserve the Union, it is necessary to refer to a map of the country, and to remember that at that time neither Texas, New Mexico, California nor Arizona belonged to the United States; that the country west of the Mississippi which fell under that compromise is that which was acquired from France in the purchase of Louisiana, and which includes West Minnesota, the whole of Iowa, Arkansas, the Indian Territory, Kansas, Nebraska, and Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Washington and Oregon, embracing an area of 1,360,000 square miles. Of this the South had the privilege of settling Arkansas alone, or less than four per cent, of the whole.

The sacrifice thus made by the South, for the sake of the Union, will be more fully appreciated when we reflect that under the Constitution Southern gentlemen had as much right, and the same right to go into the Territories with their slaves, that men of the North had to carry with them there their apprentices and servants. Though this arrangement was so prejudicial to the South, though the Supreme Court decided it to be unconstitutional, null and void, the Southern people were still willing to stand by it; but the North would not. Backed by majorities in Congress, she only became more and more aggressive.

Furthermore, the magnificent country given by Virginia to the Union came to be managed in the political interests of the North. It was used for the encouragement of European emigration, and its settlement on her side of that parallel, while the idea was sought to be impressed abroad by false representations that South of 36° 30″ in this country out-door labor is death to the white man, and that throughout the South generally labor was considered degrading. Such was the rush of settlers from abroad to the polar side of 36° 30″ and for the cheap and rich lands of the northwest territory, that the population of the North was rapidly and vastly increased—so vastly that when the war of 1861 commenced, the immigrants and the descendants of immigrants which the two sections had received from the Old World since this grant was made, amounted to not less than 7,000,000 souls more for the North than for the South.

This increase destroyed the balance of power between the sections in Congress, placed the South hopelessly in the minority, and gave the reins of the Government over into the hands of the Northern factions. Thus, the two hundred and seventy millions of acres of the finest land on the continent which Virginia gave to the Government to hold in trust as a common fund, was so managed as greatly to benefit one section and do the other harm. Nor was this all.

Large grants of land, amounting to many millions of acres, were made from this domain to certain Northern States, for their railways and other works of internal improvement, for their schools and corporations; but not an acre to Virginia. In consequence of the Berlin and Milan Decrees, the Orders in Council, the Embargo and the war which followed in 1812, the people of the whole country suffered greatly for the want of manufactured articles, many of which had become necessaries of life.

Moreover, it was at that time against the laws of England for any artisan or piece of machinery used in her workshops to be sent to this country. Under these circumstances it was thought wise to encourage manufacturing in New England, until American labor could be educated for it, and the requisite skill acquired, and Southern statesmen took the lead in the passage of a tariff to encourage and protect our manufacturing industries. But in course of time these restrictive laws in England were repealed, and it then became easier to import than to educate labor and skill.

Nevertheless the protection continued, and was so effectual that the manufacturers of New England began to compete in foreign markets with the manufacturers of Old England. Whereupon the South said, “Enough: the North has free trade with us; the Atlantic ocean rolls between this country and Europe; the expense of freight and transportation across it, with moderate duties for revenue alone, ought to be protection enough for these Northern industries. Therefore let us do away with tariffs for protection. They have not, by reason of geographical law, turned a wheel in the South; moreover, they have proved a grievous burden to our people.”

Northern statesmen did not see the case in that light; but fairness, right and the Constitution were on the side of the South. She pointed to the unfair distribution of the public lands, the unequal dispensation among the States of the Government favor and patronage, and to the fact that the New England manufacturers had gained a firm footing and were flourishing. Moreover, peace, progress and development had, since the end of the French wars, dictated free trade as the true policy of all nations.

Our Senators proceeded to demonstrate by example the hardships of submitting any longer to tariffs for protection. The example was to this effect:—The Northern farmer clips his hundred bales of wool, and the Southern planter picks his hundred bales of cotton. So far they are equal, for the Government affords to each equal protection in person and property. That’s fair, and there is no complaint. But the Government would not stop here. It went further—protected this industry of one section and taxed that of the other; for though it suited the farmer’s interest and convenience to send his wool to a New England mill to have it made into cloth, it also suited in a like degree the Southern planter to send his cotton to Old England to have it made into calico. And now came the injustice and the grievance. They both prefer the Charleston market, and they both, the illustration assumed, arrived by sea the same day and proceeded together, each with his invoice of one hundred bales, to the custom-house.

There the Northern man is told that he may land his one hundred bales duty free; but the Southern man is required to leave forty of his in the custom-house for the privilege of landing the remaining sixty.* It was in vain for the Southerner to protest or to urge, “You make us pay bounties to Northern fishermen under the plea that it is a nursery for seamen. Is not the fetching and carrying of Southern cotton across the sea in Southern ships as much a nursery for seamen as the catching of codfish in Yankee smacks? But instead of allowing us a bounty for this, you exact taxes and require protection for our Northern fellow-citizens at the “expense of Southern industry and enterprise.”

The complaints against the tariff were at the end of ten or twelve years followed by another compromise in the shape of a modified tariff, by which the South again gained nothing and the North everything. The effect was simply to lessen, not to abolish, the tribute money exacted for the benefit of Northern industries. Fifteen years before the war it was stated officially from the Treasury Department in Washington, that under the tariff then in force the self-sustaining industry of the country was taxed in this indirect way in the sum of $80,000,000 annually, none of which went into the coffers of the Government, but all into the pocket of the protected manufacturer.

The South, moreover, complained of the unequal distribution of the public expenditures; of unfairness in protecting, buoying, lighting and surveying the coasts, and laid her complaints on grounds like these: for every mile of sea-front in the North there are four in the South, yet there were four well equipped dockyards in the North to one in the South; large sums of money had been expended for Northern, small for Southern defences; navigation of the Southern coast was far more difficult and dangerous than that of the Northern, yet the latter was better lighted; and the Southern coast was not surveyed by the Government until it had first furnished Northern ship-owners with good charts for navigating their waters and entering their harbors.

The tariff at that time was forty per cent. Thus dealt by, there was cumulative dissatisfaction in the Southern mind towards the Federal Government, and Southern men began to ask each other, “Should we not be better off out of the Union than we are in it ?”—nay, the public discontent rose to such a pitch in consequence of the tariff, that nullification was threatened, and the existence of the Union was again seriously imperiled, and dissolution might have ensued had not Virginia stepped in with her wise counsels. She poured oil upon the festering sores in the Southern mind, and did what she could in the interests of peace; but the wound could not be entirely healed; Northern archers had hit too deep.

The Washington Government was fast drifting towards centralization, and the result of all this Federal partiality, of this unequal protection and encouragement, was that New England and the North flourished and prospered as no people have ever done in modern times. Scenes enacted in the Old World, twenty-eight hundred years ago, seemed now on the eve of repetition in the new. About the year 915 B. C., the twelve tribes conceived the idea of making themselves a great nation by centralization. They established a government which, in three generations, by reason of similar burdens upon the people, ended in permanent separation. Solomon taxed heavily to build the temple and dazzle the nation with the splendor of his capital; his expenditures were profuse, and he made his name and kingdom fill the world with their renown. He died one hundred years after Saul was anointed, and then Jerusalem and the temple being finished, the ten tribes— supposing the necessity of further taxation had ceased—petitioned Jeroboam for a reduction of taxes, a repeal of the tariff. Their petition was scorned, and the world knows the result. The ten tribe seceded in a body, and there was war; so thus there remained to the house of David only the tribes of Benjamin and Judah. They, like the North, had received the benefit of this taxation. The chief part of the enormous expenditures’ was made within their borders, and they, like New England, flourished and prospered at the expense of their brethren.

By the Constitution, a citizen of the South had a right to pursue his fugitive slave into any of the States, apprehend and bring him back; but so unfriendly had the North become towards the South, and so regardless of her duties under the Constitution, that Southern citizens, in pursuing and attempting to apprehend runaway Negroes in the North, were thrown into jail, maltreated and insulted despite of their rights. Northern people loaded the mails for the South with inflammatory publications inciting the Negroes to revolt, and encouraging them to rise up, in servile insurrection, and murder their owners.

Like tampering with the Negroes was one among the causes which led Virginia into her original proposition to the other colonists, that they should all, for the common good and common safety, separate themselves from Great Britain and strike for independent existence. In a resolution unanimously adopted in convention for a declaration of such independence, it is urged that the King’s representative in Virginia was “tempting our slaves by every artifice to resort to him, and training and employing them against their masters.”‘

To be continued in Part III.

Another fine installment from an earnest Christian man whose belief in the authority of scripture led him to discover ocean currents (‘paths in the sea’) as stated in Psalm 8:8, and made him a father of modern oceanography. So much for the Yankee talk about ‘ignorant Southern rubes.’

It was out and out treachery on the part of the North to subjugate the Southern states into the status of colonies, but that’s exactly what they did. A few of them even admitted as much.

Hello, German Confederate.

Allow me to first say that, your comments are “sweet music” to these ears. You might be interested in learning that a part of your first paragraph above is a main theme in a chapter (ch. II) of my book, From Ordinary to Extraordinary – The Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury, Pathfinder of the Seas. I have extracted the relevant passages from same, and post them below for your edification:

Recall as well that Mr. Maury didn’t just discover ocean currents, but also winds at sea at various places and times of year, that also contributed to his “Winds and Currents” charts. Among other things.

I cannot possibly do the extent and importance of Maury’s work justice in a combox, which is why I’ve written, and submitted for future publication, several more articles/essays on point. I have even submitted an essay dealing with the point you make in your second paragraph. Stay tuned and alert for its future publication at this site.

Thanks so much for ‘making my day’ with your comments!

P.S.: My eldest son & I were in a conference call just a few nights ago, wherein my son mentioned to me that he has taken to answering ill-informed prejudices against the intelligence of our Southern forbears by sending his interlocutors to volume I of Dr. Dabney’s “Discussions,” with the recommendation to “get back to me on the point once you’ve read it in entirety.” As you iterate, Yankee accusations of Southern illiteracy are laughable at best. At worst, they are really just projections of their own lack of real intelligence and failings, projected onto Southrons to cover up the same.

P.S.S.: Maury isn’t merely a father of modern oceanography; he is THE Father of modern Oceanography. But anyway…

Thanks again for the comments!

Thank you for the extended reply. I can see we’re ‘on the same page’ on many fronts. I first learned about Matthew Fontaine Maury from a biography segment talk at a “Great Revival in the Southern Armies Conference” in Virginia some years ago now.

Your son could also point his critics to Palmer, Thornwell, Girardeau and others. The North had no theologians to compare with the sound, incisive, biblical exegesis of such men!