April is Confederate History Month. As such, it is incumbent upon us at this site, in recognition and reverent observance of this current year’s occasion, to share with our readers some few pieces of Confederate History that, perhaps, some number of you or other have heretofore been unaware of and deprived. To that end, we offer below our first edition of Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury’s 1871 essay, A Vindication of Virginia and the South, divided into three parts.

Be it known that the original manuscript was written as a single essay consisting of over 5,100 words. It was later (1876) published as such in Volume I of the Southern Historical Society Papers. We have divided it into nearly equal parts consisting of roughly 1,700 words each, and have also added relevant hyperlinks and images, as well as having inserted additional paragraph breaks to help facilitate ease of readability. Otherwise, the essay appears as originally published. The bracketed “note” heading our Part I below was included to head the Paper’s appearance in the volume of the Historical Society Papers collection above-mentioned. Without further ado, we give you Part I of III of,

A Vindication of Virginia and the South, By Commodore M. F. Maury.

[Note.—The following paper is not the production of a partisan or a politician, but of a great scientist whose fame is world-wide, and whose utterances will have weight among the nations and in the ages to come. This able vindication will derive additional interest and value from the statement that it was not written amid the storms of the war, but in his quiet mountain home, in May, 1871, not long before the world was deprived of his priceless services. It was, in fact, the last thing he ever prepared for the press (the manuscript bears the marks of his final revision), and should go on the record as the dying testimony of one whose character was above reproach, and whose conspicuous services to the cause of science and humanity entitle him to a hearing.]

One hundred years ago we were thirteen British Colonies, remonstrating and disputing with the mother country in discontent. After some years spent in fruitless complaints against the policy of the British Government towards us, the Colonies resolved to sever their connection with Great Britain, that they might be first independent, and then proceed to govern themselves in their own way. At the same time they took counsel together and made common cause. They declared certain truths to be self-evident, and proclaimed the right of every people to alter or amend their forms of government as to them may seem fit. They pronounced this right an inalienable right, and declared “that when a long train of abuses and usurpations evinces a design the part of the Government to reduce a people to absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government.” In support of these declarations the people of that day, in the persons of their representatives, pledging themselves, their fortunes and their sacred honor, went to war, and in the support of their cause appealed to Divine Providence for protection.

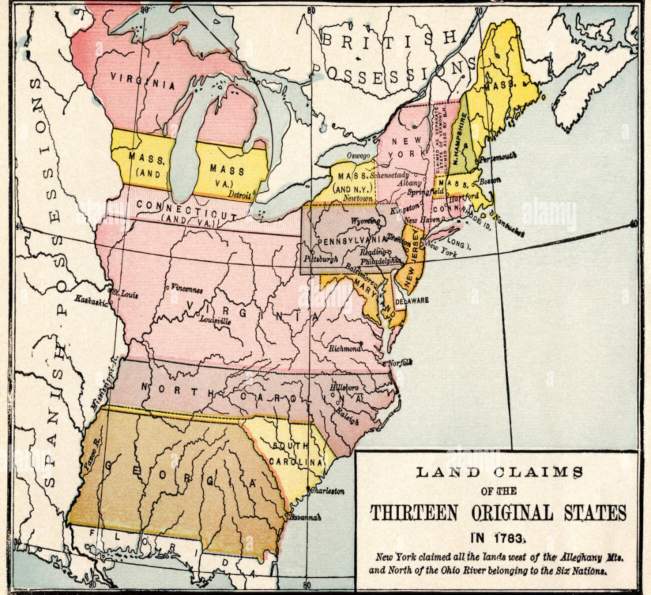

Under these doctrines we and our fathers grew up, and we were taught to regard them with a reverence almost holy, and to believe in them with quite a religious belief. In the war that ensued, the Colonies triumphed; and in the treaty of peace, Great Britain acknowledged each one of her revolted Colonies to be a nation, endowed with all the attributes of sovereignty, independent of her, of each other and of all other temporal powers whatsoever. These new-born nations were New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia—thirteen in all.

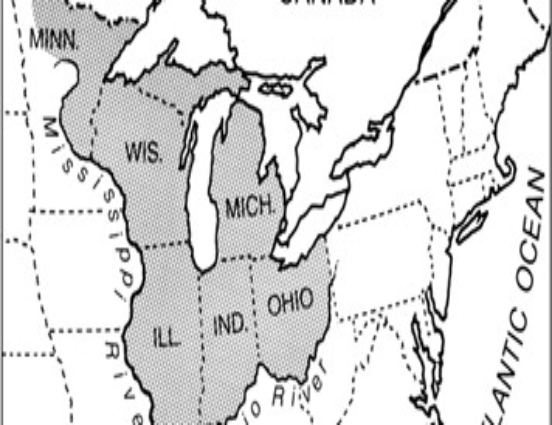

At that time all the country west of the Allegheny mountains was a wilderness. All that part of it which lies north of the Ohio river and east of the Mississippi, called the Northwest Territory, and out of which the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and a part of Minnesota have since been carved, belonged to Virginia. She exercised dominion over it, and in her resided the rights of undisputed sovereignty. These thirteen powers, which were then as independent of each other as France is of Spain, or Brazil is of Peru, or as any other nation can be of another, concluded to unite and form a compact, called the Constitution, the main objects of which were to establish justice, secure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, and promote the general welfare.

To this end they established a vicarious government, and named it the United States. This instrument had for its corner-stone the aforementioned inalienable rights. With the assertion of these precious rights—which are so dear to the hearts of all true Virginians—fresh upon their lips, each one of these thirteen States, signatories to this compact, delegated to this new Government so much of her own sovereign powers as were deemed necessary for the accomplishment of its objects, reserving to herself all the powers, prerogatives and attributes not specifically granted or specially enumerated.

Nevertheless, Virginia, through abundant caution, when she fixed her seal to this Constitution, did so with the express declaration, in behalf of her people, that the powers granted under it might be resumed by them whenever the same should be perverted to their injury or oppression; that “no right, of any denomination, can be canceled, abridged, restrained or modified by the Congress, by the Senate or House of Representatives, acting in any capacity, by the President, or any department, or officer of the United States, except in those instances in which power is given by the Constitution for those purposes.”[*] With this agreement, with a solemn appeal to the “Searcher of all hearts” for the purity of their intentions, our delegates, in the name and in behalf of the people of Virginia, proceeded to accept and to ratify the Constitution for the Government of the United States.”

Thus the Government at Washington was created. But it did not go into operation until the other States—parties to the contract—had accepted by their act of signature and tacit agreement the conditions which Virginia required to be understood as the terms on which she accepted the Constitution and agreed to become one of the United States. Thus these conditions became, to all intents and purposes, a part of that instrument itself; for it is a rule of law and a principle of right laid down, well understood and universally acknowledged, that if, in a compact between several parties, any one of them be permitted to enter into it on a condition, that condition inures alike to the benefit of all.

Notwithstanding the purity of motive and singleness of purpose which moved Virginia to become one of the United States, sectional interests were developed, and the seeds of faction, strife and discord appeared in the very convention which adopted the Constitution. At that time African Negroes were bought and sold, and held in slavery in all the States. They had been brought here by the Crown and forced upon Virginia when she was in the colonial state, in spite of her oft-repeated petitions and remonstrances against it; and now since she, with others, were independent and masters of themselves, they desired to put an end forthwith to this traffic. To this the North objected, on the ground that her people were extensively engaged in kidnapping in Africa and transporting slaves thence for sale to Southern planters. They had, it was added, such interests at stake in this business that twenty years would be required to wind it up.

At that time the political balance between the sections was equal; and the South, to pacify the North, agreed that the new Government should have no power, until after twenty years should have elapsed, to restrict their traffic; and thus the North gained a lease and a right to fetch slaves from Africa into the South till 1808. That year, one of Virginia’s own sons being President of the United States, an act was passed forbidding a continuance of the traffic, and declaring the further prosecution of it piracy.

Virginia was the leader in the war of the Revolution, and her sons were the master-spirits of it, both in the field and in the cabinet. For an entire generation after the establishment of the Government under the Constitution, four of her sons—with an interregnum of only four years—were called, one after the other, to preside, each for a period of eight years, over the affairs of the young Republic and to shape its policy. In the meantime Virginia gave to the new Government the whole of her Northwest Territory, to be held by it in trust for the benefit of all the States alike. Under the wise rule of her illustrious sons in the Presidential chair, the Republic grew and its citizens flourished and prospered as no people had ever done. [*] Proceeding of the Virginia Convention, p. 28. Code of Virginia, 1860.

During this time, the African slave-trade having ceased, the price of Negroes rose in the South; then the Northern people discovered that it would be better to sell their slaves to the South than to hold them, whereupon acts of so-called emancipation were passed in the North. They were prospective, and were to come in force after the lapse, generally, of twenty years,[*] which allowed the slaveholders among them ample time to fetch their Negroes down and sell them to our people. This many of them did, and the North got rid of her slaves, not so much by emancipation or any sympathy for the blacks as by sale, and in consequence of her greed.

About this time also Missouri—into which the earlier settlers had carried their slaves—applied for admission into the Union as a State. The North opposed it, on the ground that slavery existed there. The South appealed to the Constitution, called for the charter which created the Federal Government, and asked for the clause which gave Congress the power to interfere with the domestic institutions of any State or with any of her affairs, further than to see that her organic law insured a Republican form of Government to her people. Nay, she appealed to the force of treaty obligations; and reminded the North that in the treaty with France for the acquisition of Louisiana, of which Missouri was a part, the public faith was pledged to protect the French settlers there, and their descendants, in their rights of property, which includes slaves.

The public mind became excited, sectional feelings ran high, and the Union was in danger of being broken up through Northern aggression and Congressional usurpations at that early day. To quiet the storm, a son of Virginia came forward as peace-maker, and carried through Congress a bill that is known as “The Missouri Compromise.” So the danger was averted. This bill, however, was a concession, simple and pure, to the North on the part of the South, with no equivalent whatever, except the gratification of a patriotic desire to live in harmony with her sister States and preserve the Union.

This compromise was to the effect that the Southern people should thereafter waive their right to go with their slaves into any part of the common territory north of the parallel of 36° 30’. Thus was surrendered up to the North for settlement, at her own time and in her own way, more than two-thirds of the entire public domain, with equal rights with the South in the remainder.

[•] Slavery did not cease in New York till 1827.

To be continued in Part II.

Alas, what a mistake. These territories should have never been ceded to the general government. To appeal later to gratitude, generosity, and fairness is futile in the face of humanity’s sinful greed. The operative admonition should always be to ‘be wise as serpents’ while being ‘harmless as doves.’

Agreed on your first point; it was a colossal mistake in hindsight. But, hindsight is always 20/20, as you know.

I hope you’re not implying, in your second point, that correcting Yankee revisionist history is worthless and futile. I don’t think Commander Maury (et al) was trying to convince the Yankees in any case. And their posterity need to know who were the good faith actors, and who were not, in all of this drama. One should do all in his power to correct the perverted history of those events we’re all bombarded with by Yankees and their malevolent institutions from cradle to grave. Or so I for one firmly believe.

Thanks for the comments.

I completely agree with you, and look forward to subsequent installments. It’s just that (while reading Commander Maury) some lines from a Knight of the Holy Roman Empire on hindsight came to mind, whose autobiography I just finished:

“All the misfortune I had to endure for so long only came from me trusting too much in our agreements. Yes should mean yes, and no should mean no. … I always believed this, built all my relationships upon this, and hoped others would act the same. It was through being too trusting that I got into all my misfortunes.” p. 107.

Gotz von Berlichingen (1480-1562), ‘Autobiography’, trans. Julius Moritz

Excellent (and relevant) quotation, sir. Thank you for adding it! I had hoped you wouldn’t take my reply to your initial comment as some sort of an indictment. The next installments should be shortly forthcoming; I sent the three parts to our worthy editors as such. They (our editors) tend to do their job very well.