Author’s Note: This is the fourth entry in a multipart series examining the decline of the American Empire and what it means for the world on a regional basis. This article will focus on Iran.

Iran is an interesting case. In many ways, Iran represents the erosion of American power in the Middle East similar to the possible bolting of Turkey from NATO (which was discussed in the previous essay). However, there are also some unique aspects regarding Iran that can grant some insight into what a post-America Middle East might look like. The first thing that must be understood about Iran is the role Shia Islam plays in the understanding of itself. As the only majority Shia nation in the Middle East, Iran considers itself as the leader of Shia Islam. And in the minds of Iranians, they are the defenders of orthodox Islam, something that can be compared to how Russia developed its own Orthodox-centric concept after the Fall of Constantinople.

This is why Iran cannot break from Shia Islam, Shia Islam unites the nation. Iran is an ethnically diverse nation, only around 60% of Iran is ethnic Persian (Farsi speakers), but it is almost entirely Shia. The current Islamist government may one day fall, but Iran cannot become secular, especially not in the modern Western sense, or even become something like Jordan; any attempt to do so will break the country.

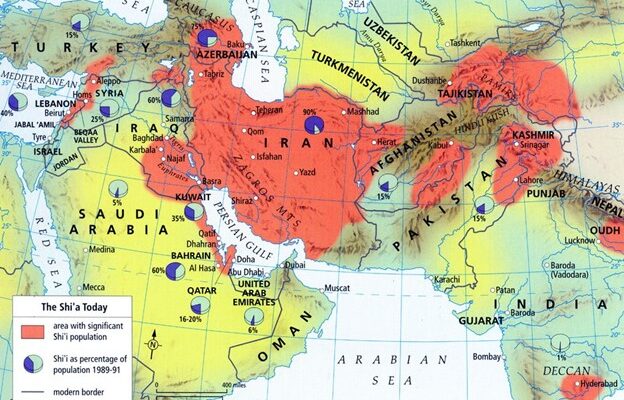

In The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Samuel P. Huntington’s thesis is that Iran is set to become a regional power, primarily due because of its large and young population, but cannot do so because it is a Shia “island” in a Sunni “sea.” As such, its ability to exercise power over the rest of the Islamic world is limited. I do not want to completely dismiss Huntington here, but he overlooks a major point. Though Iran is the only majority Shia nation, Shia Muslims do typically form a large minority in most Sunni countries. And, they look to Iran as their leader and protector. The more radical Sunni view Shia Muslims as heretics, if not idolaters, something that puts them in a dangerous position. There is always a chance that they will be targeted by Sunni violence and Iran can (and does) act against that threat.

While Iran’s embrace of Shia Islam may mean it cannot exercise full control over the Sunni world, it has captured the hearts and minds of Muslim populations that are not overwhelmingly Sunni. Syria is a great example of this, as is Iraq. While the Iraq War was dying down, the idea was floated around of splitting the country up into three parts – between the northern Sunni Kurd, central Sunni Arab, and southern Shia Arab sections. After all, as it was pointed out, the three ethnic groups clearly hate one another; the Ottomans, recognizing this, split the region up when they ruled it. “Iraq” was the creation of Anglo-French diplomacy. Part of why this proposed partition never happened was because of Turkey. There was a legitimate fear that an independent Kurdistan, in what is/was northern Iraq, would destabilize Turkey, which has its own sizable Kurdish population. But beyond that, there was a very clear reason why this was not done, an independent Sunni Arab state would become an Iranian satellite almost overnight and American leadership did not want that to happen. But even as one nation, Iran still projects a great deal of power over Iraq, thanks to the support they receive from the Shia population.

But perhaps the most fascinating country where this phenomenon plays out is in that old bastion of Sunni Wahabi radicalism – Saudi Arabia. The area in Saudi Arabia, particularly along the Persian Gulf coast, is Shia and supports Iran. There have been two uprisings, within living memory, that the Saudi military has had to put down. One was in 1979, during the Iranian Revolution. The second was in 2003, during the early days of the Iraq War. Keep in mind that Saudi Arabia was largely able to put down the uprisings because of support from the U.S. But, with declining American power in the Middle East, it is far from clear that they could suppress a future one. In the post-America Middle East, this largely hidden power of Iran can now be unleashed: any nation with a sizable Shia population must be careful in their dealings with Iran. What Huntington, perhaps correctly, saw as the factor preventing Iran from becoming a regional hegemon will still give it the power over a significant segment of the population of most Muslim nations, something that cannot be ignored by these countries.

U.S. power has allowed Sunni nations to keep Iran’s informal influence subdued, but the Empire cannot keep doing this forever. And when that happens, the U.S. will be largely dismissed from the Middle East. Rather than America keeping the Middle East stable enough to keep the oil flowing, the Middle East will either have a Middle Eastern nation as the region’s hegemon, as has been the case for the vast majority of the region’s history, or a bipolar Middle East will develop with two nations completing for control over the region, likely Turkey as the leader of the Sunni world and Iran as the leader of the Shia world. Neither of these nations are Arab though, and that could lead to Arab Nationalism making a comeback in a more distant future. As of right now, religion, rather than ethnicity, is the center of identity in the Middle East and a Turkish-Iranian rivalry would fit into this very well. In turn, this would allow the region to further marginalize the U.S., creating a major blow to the economic power of the Empire.

Another advantage Iran has it that, typically, Middle Eastern “group loyalty” is U-shaped: there is a great deal of loyalty to one’s tribe and to greater Islamic civilization, but comparably little for the nation-state. Iran, however, is ancient and has developed its own unique identity, something enforced further by the special role Shia Islam plays into Iranian identity. This gives Iran a built-in stability that will easily allow it to become a hegemon, there is a greater amount of homegrown loyalty to Iran than there is in places like Yemen or Saudi Arabia.

But even beyond ideology, Iran also has a large population, and unlike the majority of Europe, it is young, something that is highly important for an up-and-coming nation. All of these factors combine into a vibrant Iran capable of exerting power over the Middle East, especially when the U.S. no longer has the allies to counter it. Much has been predicted on the possible erosion of American power in the Balkans and the Black Sea. And in that scenario, it is hard to imagine the Empire’s power in the eastern Mediterranean not further decimated. Greece and Israel, as the remaining exceptions, would remain as “strong” American allies. Unlike the potential loss of the Black Sea and the Balkans that would reduce the Empire’s sphere of influence to pre-1991 levels, an emerging Iran, paired with diminished American control of the Middle East, would signal a rapid collapse of global Pax Americana.