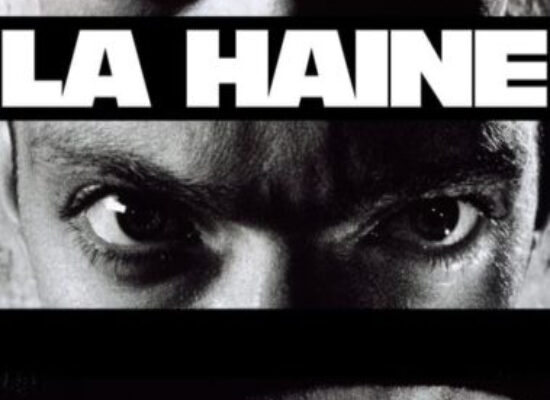

2022 marks the 27th anniversary of the cinematic release of the French movie La Haine (“Hate”), a “day in the life” picture of three young immigrants in the banlieue (public housing projects) on the outskirts of Paris. The three young men represent different strands of French immigration: Vinz is from an East European Jewish family, Saïd is Arab, and Hubert is African. The local atmosphere is charged, in the immediate aftermath of riots, and a young beur (French immigrant of North African origin) named Abdel is fighting for his life in hospital, while nervous police patrol the streets. Vinz vows to avenge Abdel if he dies, by killing a policemen with the police revolver he grabbed during the riots. The camera follows the three characters around through their different, often violent, escapades to a bloody denouement.

The film was a huge and controversial success when it came out. Shot in grainy black and white, in an almost documentary style, it portrayed the life of France’s “ghetto” and social problems as never before. It sparked tremendous debate in France. Alain Juppé, then-Prime Minister, ordered a private screening for his cabinet. At the 1995 Cannes film festival, police pointedly turned their backs on French-Jewish director Mathieu Kassovitz, perceiving the film to be denigrating them (several scenes of police brutality are featured). Riots took place the following month in Noisy-le-Grand, east of Paris, after the death of a young immigrant who crashed his motorbike while being chased by police; these were partially blamed on the film – “life imitating art” – but would probably have taken place anyway. France in 1995 saw riots, bombings and the first stirrings of Islamic fundamentalism among the disaffected banlieue youth.

The movie is worth watching again. And it begs the question: what – if anything – has changed?

La Haine feels like it was shot yesterday. It does not have the dated feel of other 1990s movies, instead seeming urgent and contemporary. We remember the riots of 2005, and the continuing chaos in France since then. The immigrant youth are still angry, the police still crack down, and native French Whites are either appeasers or else pivot to Marine Le Pen (who received a significant 33% of the vote in 2017) or Éric Zemmour. However, if anything, the crisis depicted in the movie has deepened. An estimated 15% of France’s population are now non-White. Unemployment in 2021 was officially 8.1 percent, well above dynamic economies in Germany and Britain. In the last decade, we have seen radical Islamic ideology penetrate the banlieue, to the extent that mosques across France have been closed by the government, horrendous terrorist attacks have been committed in places like Nice and the Bataclan theater, and hundreds (perhaps even thousands) of French Muslim youth have travelled to Syria to join ISIS. Whites have also taken to the streets in the form of Gilets Jaunes. COVID-19 may have been a gift to President Macron and the elites he represents, in terms of clamping down on the populace and buying time, but as the economy reopens serious unrest may ensue, particularly if even more millions remain out of work. A bloody confrontation between rioting immigrants and the Gilets Jaunes could be the spark that lights the powder keg, as could a successful Zemmour bid for the presidency.

For all the chatter swirling around La Haine at the time, it is clear that the prophecies and warnings hinted at in the movie have not been heeded. Lessons have not been learned. The ugly world it displays has not been ameliorated. One is struck by the bleakness, boredom, and blankness of it all. The actors speak a joyless, debased form of French slang called verlan (literally “backwards” – l’envers – backwards; words are inverted, thus femme (woman) becomes meuf, arabe becomes beur, français is céfran) which lacks the bright charm of other argots such as Cockney rhyming slang, instead furnishing a linguistic symbol of destructive revolt against the dominant order. Nobody has a job; scene after scene shows bored young men hanging around, smoking cannabis, and conversing aimlessly. Nobody appears to have any imagination or will to positively change things; they are stick-in the-mud urban bumpkins, going nowhere as the same French State that feeds and houses them is cripplingly unable to foster the conditions for opportunity and business creation.

The State is also the father figure that they all seem to lack. They rebel against a brutal, faceless faux-paternal authority, while no real fathers are to be seen. In this sense, the film could have been set in a black neighborhood in South Chicago, or a Glasgow tower block estate. The emerging Western welfare state and jettisoning of sexual morality since the 1960s have spawned generations of young men without older male role models, with wretched results. Men incapable of self-discipline, or fatherly discipline and guidance when they beget their own children. Without the vital channeling of restless male energies into building a family, polity and civilization, men lapse into violence and destructive urges.

Civilization and polity are in short supply in La Haine. An incongruous mural of Baudelaire glares down at the threesome late in the film, as if somehow this portrait is expected to atone for the brutalist Bauhaus architecture of a human zoo. It is hard not to feel sorry for Vinz, Saïd and Hubert as men cut off from tribe and culture. Apart from a brief glimpse of a small menorah in Vinz’s mother’s apartment early on, there is no indication that any of the youths are connected to their racial roots in Africa or the Middle East. Alien to the White racial culture of their adopted country, they take solace in soulless Hollywood movies and American hip-hop, which only emphasizes their deracination.

Yet the boys are still yobs, unable to talk to women or act in a civil and gracious manner. There is one telling scene where they go to a night showing in an art gallery. Greedily helping themselves to food and wine, their attempt to chat up a pair of arty French girls degenerates into an aggressive stand-off. And the art itself is the epitome of decadent, meaningless, post-modernist nonsense. “Awful! Awful!” exclaims Saïd in bewilderment at one piece – which appears to be some kind of toy plastic dog glued to a blank canvas. It is as if the snobbish Le Corbusier types who created the banlieue are as morally bankrupt as the petty criminal youths they end up ejected from their gallery, and as disconnected from their own racial, cultural and religious history.

Religion is nowhere in La Haine. There is no redeeming Christ, nor any rabbi in Vinz’s life. This is the triumph of the French secular state; but it has left a void, which as we know is presently being filled in the banlieue by fundamentalist Islam. The burning of Notre Dame in 2019 was a fitting symbol of what France has become – and perhaps a glimpse of the way out. As the country seems to be careering headlong towards another revolutionary cycle, rejection of the prevailing atheistic orthodoxy and a rediscovery of France’s traditional faith and roots may be the only way to avert catastrophe and the dire dystopia envisioned by Kassovitz.

Towards the end of the movie, the protagonists walk past a billboard featuring the Earth in space and the slogan “Le Monde est à vous” (The World is Yours). Saïd crosses out the “v” and writes an “N” above: now “The World is Ours.”

Is it too late for a deeply divided France to prevent this from becoming reality?

-By Paddy

O I’m a good old rebel, now that’s just what I am. For this “fair land of freedom” I do not care at all. I’m glad I fit against it, I only wish we’d won, And I don’t want no pardon for anything I done.

L’envers is exactly what the left leaning cultural marxist of America cling to. Every and all degenerate trends adopted by low IQ cultures are consistently adopted as norms as they are inserted into the life styles of the most current generations of youths. Tattoos on display, public twerking and eubonic speech seem to codify the necessary indicators whereby these groups promote their baseless life philosophies. Rewriting established standards of acceptance to include loosers, dopers and villans seems to broaden some grip on security for those who have achieved basically nothing. In a battle theatre, these miscreants are sumarily schrapped out of concern for the function of the unit as a whole. Hope no war breaks out!