I love the South, you have to in order to write for Identity Dixie. But, I also love movies and have been fond of horror films for as long as I can remember. With that in mind, I decided to combine two of my great loves to present to our readers a series of 13 horror films that deal with distinctly Southern themes. There will be no Deliverance or The Texas Chain Saw Massacre on this list. Don’t get me wrong, I love both films, and think that they should be required viewing for any Yankee thinking about moving to Dixie, but both are also well known and popular. Even people who have never seen Deliverance know what “squeal like a pig” means and people who have never seen The Texas Chain Saw Massacre know of Leatherface. Instead, I will focus on lesser-known films. Also, I will prioritize low budget films – i.e. hixplotation (hick exploitation), as this is what I’ve historically gravitated towards. Some of these are legitimately good movies, others are so bad they are good, but they’re all movies I love. The films listed here are in chronological order.

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964)

Two Thousand Maniacs! is the film that more or less invented the “Don’t Go Down to Dixie” movie trope, films about Yankees coming to the rural South and having a run-in with the locals that doesn’t end well. Two Thousand Maniacs! tells the story of Pleasant Valley, a town destroyed during the War by a group of Yankee soldiers. As it turns out, the town is cursed and every hundred years ghostly vengeance returns to lure unexpecting Yankees to their very gory and imaginative deaths.

Now, watching “Don’t Go Down to Dixie” films has always been a little cathartic for people like me, but what makes Two Thousand Maniacs! stand out is how demented it all is, almost as if it’s inviting the audience to join in on the festivities, which is odd considering the film’s director hailed from Chicago. Two Thousand Maniacs! is not a good film by any conventional metric. The acting is terrible, even for the budget, and while the gore is plentiful, the special effects are so terrible it renders it more of a comedy. Still, it is a great film to gather some friends together (with some beers) and watch Yankees buy the farm. Plus, it was filmed in the South – St. Cloud, Florida, specifically, and even casts the locals as extras (and do they ever get excited about the possibility of gettin’ some Yankees). Of course, the theme song can’t be beat.

The South’s Gonna Rise Again! Yeee-ha!

The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972)

Charles B. Pierce was a director, mostly active during the 1970s, that stands as one of the more fascinating regional filmmakers of the era. Southern Arkansas and northern Louisiana is to him something like what Little Italy in New York is for Martin Scorsese, it’s where his people come from and he delights in telling their stories. His debut film, The Legend of Boggy Creek, is built around the real-life legend of the Fouke Monster, a bigfoot variation that is said to inhabit the woods around Fouke, Arkansas. The movie helped jump start a mini-craze of bigfoot movies in the 1970s, but, at least in retrospect, its biggest impact has not been in its material, but rather in its style, as the film structures itself as a documentary, complete with grainy footage, interviews with people who claim to have seen the monster, and reenactments.

The film is the forerunner of the “found footage” movie theme – the makers of The Blair Witch Project have admitted as much, so take that as you will (I still say that is one of the worst films I have ever seen). It was a staple of late-night showings for decades throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and is still a creepy and effective film. The Legend of Boggy Creek is a great example of the old adage “less is more,” as Pierce is far more interested in building mood and showcasing an area and people he clearly loves more than depicting violence. It was even rated “G” back when it was first released.

Stanley (1972)

If Martin Scorsese had Little Italy and Charles B. Pierce represents south Arkansas and northern Louisiana, then William Grefé is south Florida – it was where he was from and was drawn to the local stories. Coming out a year after Willard, Stanley is admittedly a cash-in of that earlier film, but is still works. Replacing rats with snakes, Stanley tells another story of a misfit who uses animals to get revenge on his enemies. Although, this time there is a heavy environmentalist and anti-development message, which is interesting because this was around the time that south Florida was transforming from a land of hardscrabble Dixians and Seminoles, both eking out a meager existence in the swamps, to a land of Yankee retirees and Cubans.

The film is a lot better acted than one would expect, I especially liked Alex Rocco (Moe Greene from The Godfather). Stanley certainly isn’t Willard, but it is a lot of fun and the message works better than it should. Grefé’s fascination with “old” south Florida goes a long way to make this more enjoyable, it’s easy to see his passion. Born in Miami in 1930, he saw that transformation first hand, and he doesn’t see it as the march of progress but rather the loss of something we will never get back. Still, it is better with a few friends and a few more beers.

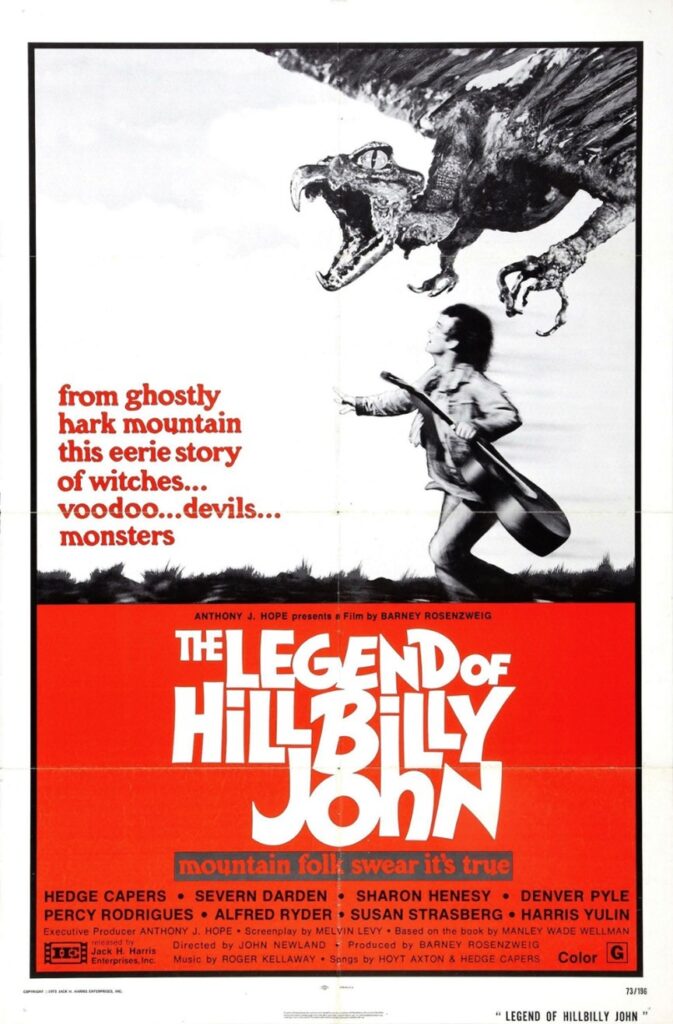

The Legend of Hillbilly John (1972)

One reason I have always been drawn to 1970s cinema, especially low budget 1970s cinema, is that I love the risk-taking aspect of it. They were made by people who were trying to break new ground and were willing to throw anything at the wall to see if it would stick. Such a mentality is going to produce its fair share of bad films, and a few so terrible that they’re actually enjoyable, but its still going to create something really impressive. And, I would rather watch a “bad” movie from someone who is putting his heart and soul into a truly bizarre idea than a by-the-numbers snooze fest from Marvel. The Legend of Hillbilly John is one of the best examples of the “let’s see if this works” mentality of 1970s cinema.

The plot is a mere excuse for its visuals, as an Appalachian ballad singer encounters various forms of the devil, all in the shape of monsters in his travels. It almost feels like a cross between “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” and Ray Harryhausen. Much like The Legend of Boggy Creek, it has a genuine love and fascination with the various local legends that permeate throughout Dixie and its wonderful to see those brought to life with far better special effects than I expected. It’s an exercise in style, for sure, but few films have done as great of a job at bringing the legends I remember from my childhood to life.

Race with the Devil (1975)

Taking elements from two staples of 1970s drive-in cinema, the road film and the Satanic cult film, Race with the Devil is a wonderful example of both, and having one foot in both genres. It’s the story of two motorcycle salesmen and their wives on the run from a Satanic cult in their RV. At the heart of what makes this work as well as it does, is the relationship between Peter Fonda and Warren Oates. The single biggest reason why “opposites attract” films fail is because viewers can’t believe that the characters could actually be friends. However, Fonda and Oates play off each other very well in the movie. Fonda is every bit as bold and brash as one would expect, and Oakes is much wearier, a man deeply cynical about the world, the type of character he excelled in portraying in his career, but they have great chemistry. Their friendship feels authentic and they compliment each other.

The movie was filmed in Texas (back in the 1970s the Texas government was giving tax breaks to filmmakers who would come there) and it makes wonderful use of the Texas landscape. Ultimately, the film is the product of the post-Watergate era paranoia, a time when distrust in the government was seen as normal and not a sign of needing to be on a watch list. The film still holds up today.

The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976)

Charles B. Pierce is back with another film about a local legend in southwest Arkansas that utilizes documentary elements to tell its story. This time the subject is the Texarkana Phantom, a still unknown killer who terrorized the city in early 1946 (the move takes place mostly on the Arkansas side of the border). The movie is not accurate in the least, but I still like it. The Legend of Boggy Creek is Pierce’s first and most well known movie, but The Town that Dreaded Sundown is his best work. It stands as an example of the voice over done well, as it helps enhance the documentary feel of the story. All historical inaccuracies aside, its somber and matter of fact tone make it feel like a true crime documentary and the results are fascinating. I enjoyed seeing how Pierce developed as a filmmaker since Boggy Creek using similar material.

Once again, his love of the land and its people comes through. Ben Johnson (from The Wild Bunch and Junior Bonner) is here and does a wonderful job, elevating the material nicely and giving it a sense of gravitas I was not expecting. As a bit of trivia, this is where Jason’s bag mask from Friday the 13th, Part II came from, before he donned his famous hockey mask. The film is still publicly shown in Texarkana around Halloween. It was also followed by a meta-sequel/remake of the same name in 2014, which was far better than I anticipated.

Squirm (1976)

Squirm is, without a doubt, the best killer earthworm movie ever made. Alright, all kidding aside, this was yet another late night staple on cable, and one I remember very well. Set in the fictional town of Fly Creek, Georgia, a bad storm downs an electric line that turns the earthworms into carnivores with a distinct taste for human flesh. It’s one of the dozens of films that came out in the wake of Jaws and is, along with the admittedly superior Grizzly, one of the first of those types of films. Squirm is another example of the “throw it at the wall and see if it will stick” mentality that makes 1970s low budget cinema so fascinating.

But, what is also great about this film is how sincere it is. This is not a parody or a deliberate attempt to make a Mystery Science Theater 3000 type movie, a show that I hate (Squirm did wind up on an episode). Nope, this was made by people who thought a movie about killer earthworms would genuinely work, and the strange thing is it does. As with several other films on this list, this is a movie to get some friends together with a case of beer and marvel at a lost era of filmmaking, one that actually took risks and where ideas like this were put on film. It’s the sort of experience that must come organically, no synthetic attempt to create something like this, like Sharknado, can ever top the real thing.

Eaten Alive (1976)

Tobe Hooper followed up his classic The Texas Chain Saw Massacre with Eaten Alive, a movie that takes elements of his earlier film, but makes it even more Psycho-like while also throwing in a bit of Jaws for good measure. I tend to think Hooper is an underrated filmmaker anyway; he has the reputation for only making one good film, but this shows he was far better than that. Once again set in Texas, it’s about a murderous hotel owner who feeds his victims to his pet crocodile – like I said, Psycho meets Jaws meets The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is the best way to describe this movie. It’s a much more polished film than Hooper’s most famous one, at least on a technical level, and while that does mean it lacks the punch of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, even if it lacks the simplicity of that film, it still works as a gritty horror film.

For as much as it borrows from those other films, it never feels like a rip off, mostly thanks to the madcap feel Hooper creates that makes this feel fresher than it should. This is certainly not a film for the squeamish, but this is still the closest Hooper ever came to recapturing the feel of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, even as I remain a fan of his work, at least up until the late 1980s. Also, worth checking out for the chance to see Robert Englund, sans the Freddy Kruger make-up.

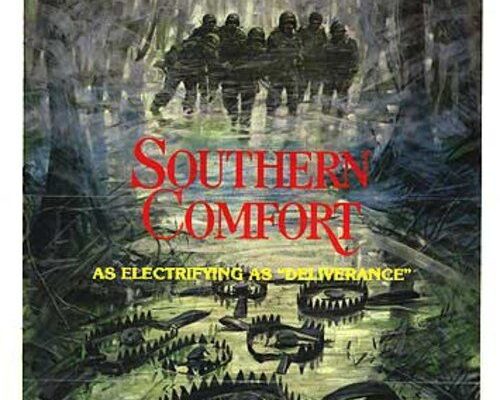

Southern Comfort (1981)

Southern Comfort is an important film for me because it’s the film I wanted to make. Years ago, back when I watched stuff like Deliverance, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and Two Thousand Maniacs!, I came up with an idea to take the basic structure of these films, but put the audience on the side of the hicks: obnoxious Yankees (oh, but I repeat myself) come to the South, do something horrible, and get killed by the rural natives. Then, I saw Southern Comfort and realized that the idea had been done 25 years earlier. Set in Cajun country, Southern Comfort is about a group of national guardsmen, who while on maneuvers, steal a boat from the Cajuns, and, as a joke, fire blanks at them. In turn, this causes them to be hunted down by the locals.

It’s a tense and downright frightening film. Walter Hill is best known for The Warriors and 48 Hrs. but he shows a real knack for directing horror here. He does a wonderful job crafting a sense of paranoia that allows the audience to be placed in the midst of soldiers trying to fight guerilla war. Needless to say, Southern Comfort is a film very much inspired by the Vietnam War, but it also works because of how it takes a fairly familiar formula, and turns it on its head. These are not merely misguided weekend campers out of their element, as in Deliverance, but rather soldiers who have no idea how to act in someone else’s home.

Dark Night of the Scarecrow (1981)

Dark Night of the Scarecrow is the most anti-Southern film on this list, as it portrays us as narrow-minded and violent vigilantes. Race is not the subject here, but rather mental deficiencies – as Larry Drake plays a retarded man who befriends a young girl, and the majority of the town distrusts the friendship. The girl is attacked by a dog and is saved by Drake, but the townsfolk blame him. His mother hides him in a cornfield, disguised as a scarecrow, but he’s found and killed. After he is murdered, the vigilantes find out what really happened and cover it up. They are then killed themselves, one by one, by a scarecrow.

The movie may be anti-Southern, but its still a good film, mostly because of how it demonstrates the importance of restraint. This came out in 1981, during the peak of the slasher film, and while so many other films were trying to one-up Friday the 13th, Dark Night of the Scarecrow, though it can be loosely described as a slasher film, will have none of that. In fact, this was made for television and thus has minimal explicit violence. It feels very much like a Twilight Zone episode. Yet, it is far more frightening than the vast majority of its contemporaries that were trying to piggyback off Friday the 13th. If you have seen Dr. Giggles, you know Drake is the only reason this film is even watchable, and with good material Drake manages to shine.

They Don’t Cut the Grass Anymore (1985)

The common thread that connects the “Don’t Go Down to Dixie” genre is simply that a group of outsiders travel to rural Dixie where they are killed off due to some transgression towards the locals. They Don’t Cut the Grass Anymore is essentially the “Don’t Go Down to Dixie” film in reverse – two Texas gardeners decide they’ve had enough of Yankees and travel to Long Island to take the fight to them. “Fight them over there or fight them over here” is apparently their motto. What makes this film stand out is its attitude. As with Two Thousand Maniacs!, They Don’t Cut the Grass Anymore was made by a Northerner but is bizarrely sympathetic to the gardeners. Nathan Schiff is a native of Long Island, but he apparently thinks New York yuppies are so terrible he’s siding with the Texans (I have at least one friend up there that agrees).

Needless to say, this is not high-brow cinema, but it has an infectious sense of enthusiasm that makes it a lot of fun. As with Two Thousand Maniacs!, the gore is plentiful, but the poor special effects render it more comical than gross, let alone scary, which works well for the overall tone of the film. A film about a couple of Texans killing New York yuppies, where the Yankee director is on the side of the Texans, is going to work better with a less serious tone.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986)

I know I said I wasn’t going to discuss The Texas Chain Saw Massacre because it is too well known, but its first sequel is still underappreciated decades after it came out. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is a perfect example of how to make a sequel to a classic film – don’t try and redo what was done before. Aliens would have likely failed had it tried to recreate the slow burn and atmospheric tone of the original, but by being an action film, it became a classic in its own right. Are there exceptions? Sure, The Godfather, Part II is one of them, but the vast majority of the time it is a far better idea to try and do something different.

Such is the case with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. The tense and serious survival horror tone of the original film, one that relished in its minimalism, is replaced with a film that revels in its 1980s excess, a film fully willing to introduce comedy, and while it certainly is not as good as the original (which is my favorite horror film), it still stands strong in its own right. It also has a highly unusual soundtrack for a horror film. Unlike the original that used industrial sounds, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 uses an electric collection of alternative rock and new wave rather than something that sounds more like a traditional horror film score, like Halloween. It’s one of my favorite soundtracks of the 1980s, and not just horror.

Hunter’s Blood (1986)

During the 1970s and 1980s, the first generation of suburbanites reached middle age, an important event as it meant that now those in charge of the nation were people who had no real connection to the land. But, the instincts cultivated over generations of rural living would not go away. And, as such, there was a rather large group of men that were trying to scratch that itch. Thus, the weekend warrior was born – men who longed for adventure because they lived in a world that was based on safety. The main problem was, more often than not, that these men were well out of their element. Deliverance certainly touches upon this, Burt Reynold’s character is the only one of the bunch that has any real idea what he’s doing. However, Hunter’s Blood, released over a decade later, furthers that idea by bringing it to the forefront of the film.

It’s a horrifying and tense film and a great example of the “redskins to rednecks” thesis – the idea that films like this one are Westerns, but with rednecks taking in the traditional role of “redskins,” after the traditional depiction of American Indians as savages was deemed politically incorrect by the late 1960s. The men in this movie, men on a deer hunting trip, are trying to scratch an itch and come across rednecks who actually know the land. What they see as a fun weekend, others see as a way of life, and to see the clash between them gives the film its strength.

Happy Halloween!

Great list man

Really appreciate the list, haven’t heard of a number of them until now!

Many don’t care for MST3k, however there are many movies I never new existed without their program, “Squirm” & “Boggy Creek II: The Legend Continues” among them. After seeing them on their related episodes, I found the unedited versions.

While not exactly a horror movie, “The Enchanted” (1983) is strange and has some great depictions of rural Florida, related folk stories.

Gotta love “Maximum Overdrive” too.

Excellent list. If you’re going to watch ‘The Legend of Boggy Creek’ then you may as well make an evening of it to watch ‘Return to Boggy Creek’ and the somewhat oddly titled third film, ‘Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues’. The odd naming convention may be due to the fact that Pierce was only involved in the first and third movies, but that’s only a guess.

Don’t forget one of Charles Pearce (Hampton, Ark) was also a talented screenwriter responsible for one of the most memorable lines in the movies.

“Go ahead. Make my day!”

Pearce admitted that he did not originate Dirty Harry’s iconic line, but that he copied it from something his father said to him back when he was a rebellious teen.

Squirm is a great movie. I love the characters. The young man, the girl he is interested in and the younger sister, good writing, good acting. I saw Boggy Creek as a kid and the documentary style messed with my little head. I am going to hunt the others down. I had no idea there were more Boggy Creeks.

Thanks man. Also, love the terminology of hixplotation, I will use it for reference next time I’m harping about not updating our terminology in the South. Nice list and thanks for sharing. Now where to find them…..