“I don’t like cars buzzing around. I don’t even want a piece of concrete in my town.”

“Country Boy,” Ronnie Van Zant

Well intended ideas more often than not become perverted temptations. There are countless examples.

On the individual level, a 15 minute DMT trip can deliver a profound, life-altering “spiritual” experience aping what normally was something only few attained, if ever, after a lifetime of patient practice, mediation, and humility. Pursuit of intimate communion with God is good. Short-cutting it with bio/chemical hacks provides undeserved and ill-prepared for contact with at best things one is not ready to handle, at worse diabolical invasion.

On a macro level, the public facing internet as a way to communicate quickly and to share information at scale is a fine idea. Its current ubiquitous and commercialized application that makes it possible for any person, anywhere, to have anything accessed or delivered on demand…now if possible…is a disaster. The internet has freakishly enhanced the worse elements of QVC and deformed humanity into tape-worms with unquenchable appetites demanding immediate gratification. Not too long ago acquiring knowledge and goods required additional cost, thought, effort, and reflection. I remember vividly the workplace before and after the internet was installed. You are coping and you are an addict if you believe life is better now with limitless access to goods, information, and entertainment than before.

But of all the things that will provoke my Neo-Luddite ire, few are on par with the devastating and irreversible impact on traditional life, social stability, and the long-term happiness for mankind as the modern interstate highway system.

Surely You’re Not Saying…?

The cowboy once symbolized the essence of American personal freedom, a man assessing opportunities at the edge of the frontier, adventure just beyond if he dared. But it was understood you had to work your way to get to the vista the Marlboro man was enjoying and it was not for everyone. A cheap version of this was made possible by the car but became democratized and commoditized by the interstate highway system.

Yes, there is something irresistible about being called to the open highway, windows down, the landscape flying by, the music loud, excited about “going somewhere.”

And that’s the point, it really is irresistible. The highway system too easily satisfies a primal itch to seek new lands and adventure but without the effort and the necessary but enjoyable hardship that filtered out the mildly curious and lazy. The state and rural roads were slower, less direct and thus were a barrier for many which in turn preserved the actual frontier. Importantly, it preserved the idea that a frontier even existed and was something to long for…maybe someday you’d be worthy to make a real journey.

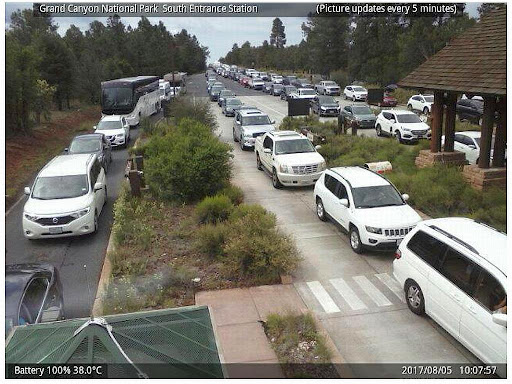

Visit Yellowstone or Grand Canyon National Park and thoughts of rampaging grizzlies and a violent Navajo revolt will soon fill your imagination. Exits off I-90 and I-40 made these frontiers as easy to get to as Six Flags.

The high-speed interstate highway system dangerously over-delivered. Like the good that the internet could have been had we the ability to be creatures of moderation, we overdosed on highways. We can’t handle the freedom they offer any more than we can handle an unearned encounter with the spirit world of DMT and whatever imposter god is there waiting to greet you on the other side.

Yes, it would be hard to imagine not having access to the open highway now and the “freedom” to smoothly traverse a continent in a few days.

But at what price? Is this easy ability to travel and uproot actually a benefit once the costs are fully accounted for?

I suggest that the interstate highway system took the good of local roads to a scale and scope that is now a force of evil and the uglification of the world.

Bait and Switch

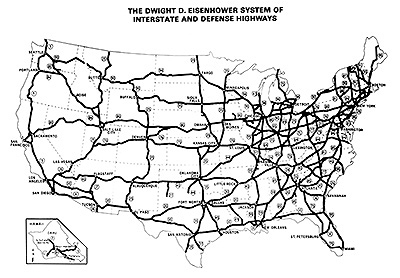

The case to fund the 41,000+ miles of limited-access national highways was made in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 (called the Interstate Highway Act).

It was summarized in four points:

- To safely connect major metropolitan areas

- To decrease congestion around major cities and revitalize them

- To improve the economy (bad roads and traffic congestion diminished effective transportation of manufactured goods)

- To provide a system for defense

It was supposed to take ten years to complete and cost $25 billion. It took 65 years and the final price tag was $41 billion with the average cost per mile being $639,000 in rural areas and $3,658,000 in urban areas. When state and other monies are actually factored over time, the real cost is estimated to be north of $420 billion.

In spite of the manipulative rhetoric selling the idea to the people including national defense and the need to be able to transport military and supplies and evacuate cities in the event of a nuclear attack, the real purpose, going back as far as the 1930s was always a fundamentally economic one: to connect cities and towns throughout the country in order to lubricate the business of doing business and super charge consumption.

Initial public enthusiasm fell off almost immediately once the work began in earnest in 1957.

The Interstate Highway Act brought tremendous changes to the country in ways we can hardly appreciate now having grown up with it, again not unlike those of us who remember life before the internet and the degraded experience post its deployment.

The superhighways chopped up cities and especially poor areas and ethnic neighborhoods. In New Jersey, the interstate going through the Oranges bisected a massive cemetery. From San Francisco, to the French Quarter in New Orleans, to D.C. and Baltimore, people revolted when they understood the scale of the deformity being planned.

Towns that once had healthy local businesses dependent on state road traffic were isolated and died overnight. Their local economies being ruined, people—and especially the young—were forced to leave home and follow the black top to new opportunities.

It wasn’t just the rural areas that were forever changed. Rather than improving cities as promised, their populations declined as those who could flee the city left and chose to commute instead, taking their tax dollars along with them.

From Florida to California, I-10 turned some of the nation’s fastest-growing and historic cities (Pensacola, New Orleans, Houston, San Antonio, Tucson, Phoenix) into car-dependent, sprawling hideous metropolitan areas with hollowed out city centers.

And the cost of the millions of cumulative hours spent commuting is a very real cost indeed one that includes far more than just spent fuel and pollution.

I Want a White Picket Fence With A Dog in the Back and a Two Car Garage As a Matter of Fact

Commuting on the new superhighways made the birth of the suburb’s isolating faux communal existence possible. Suburbia atomized the population and transformed culture in profoundly negative ways. Countless books, movies, sociological studies, and for those who can remember, our own lived experience, have tried to express and contrast the downgraded life of suburbia with that of the small town and the established city neighborhood.

Levittown, NY (on Long Island) was the first planned American suburb. It became the model for suburban sprawl with the interstate being an essential ingredient for them to exist and for men to be able to leave home, their children to be bussed, and for a generation of wives to find ways to self-medicate and perfect the mid-morning cocktail as they tried to understand the emptiness.

A Syllabus of Errors

The list of interstate highway negatives is a long one, but a few things stand out for me:

- They have made huge parts of urban areas ugly garbage strewn dead zones. Outside the city, highways are often banked so high you can’t actually see the landscape and are stuck in a monotonous tunnel.

- A mile away, the highway still roars like an unvarying ocean. There is never peace.

- The very idea of Place is gone and has been replaced by the rootless cosmopolitan lifestyle and mindset.

- The colonization of rural America by transient people and rent seekers with outside developers building suburbs that forever ruin the land and local culture.

- The fracturing of families, as it is now accepted that children will simply leave and pursue the siren song to go anywhere. They are not to blame for wanting to go as suburbia or their broken small town offers almost nothing worth staying for.

- In conjunction with mass entertainment, interstates helped flatten regional cultures into an indistinct blob that mixes and dilutes races, regions, and local cultures.

- Appalachia and the endless hollers were preserved by being inaccessible. Bob Childress’ autobiography, The Man Who Moved a Mountain chronicles the fiercely independent wild communities of Virginia’s Blue Ridge that, in spite of all their occasional dysfunction, were worthy of preservation. I-81 and 1-77 helped spoil this entire region.

- Mega malls and franchise driven highway-exit culture blandly dominate. There is literally no difference worth noting between places in the country within miles of an interstate.

- And on and on.

The interstate system has made the world too accessible, too small, too common, too ugly. We were made for the human scale…not this.

Edward Abbey, American author, iconoclast, and all around loose cannon, created a character named Hayduke who in the Monkey Wrench Gang has a recurring refrain about the damage done to the countryside in general and by the highway system in particular. Hayduke says, Beautify America and burn a billboard down.

But the damage is done, Hayduke. Lamentations only. It is important, however, to remember that we have suffered a loss and that it wasn’t meant to be this way.

The road to hell isn’t paved with good intentions, it is simply paved.

‘Cause down in Alabama, you can run, but you sure can’t hide.

Good article sir., and it is a trend I have noticed in others, the longing for borders again, the feeling of existing disconnected from people you despise and the ability to grow upright instead of on the artifcial trellises they lay out for our communities.

The interstate was many things, foremost a governmental boondoggle for political gains and faux job creation, but its primary purpose was to break down our borders and connect us to be we were best to not be connected to in the first place.

There can be no sanctity when anyone can just drive back and forth across your home on a whim, to plop down where they please, rub the magic dirt on themselves and begin telling you who “we” are. The interstate is just another example of the evil that is only made possible by a Federal Government that should have never been.

Excellent! Very strong closer👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

Building away from cities, limiting size through strict zoning, and controlling everything as a corporate entity ( like Disney) is a plausible future for preserving our culture and people.

Ever notice that the people complaining about life in small towns because “everybody knows your business” are usually women. In my experience, 100% have been women. What would they like to do, and hide, one wonders. The highway system gave them the ability to freely travel from megalopolis to megalopolis, and live in relative anonymity.