In 1879, Pope Leo XIII issued the encyclical Aeterni Patris in which Thomism, the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, was to be set as the centre point of Catholic thought. In this same year, the Apparitions of the Blessed Virgin in Knock in Co. Mayo, Ireland occurred. Catholicism in Ireland took on a deeply devotional and mystical character, diverging (once again) from the mainstream in Rome. This Irish Catholicism crowded out and prevented Thomism from taking hold to any significant degree in Ireland. 1879 was also the year of Patrick Pearse’s birth.

Last Christmas season, an interesting article was published on Identity Dixie about Patrick Pearse. I circulated it to Irish Nationalists to positive reception. I would like in this piece to add some resolution to one aspect of that article – Pearse’s alleged homosexuality, and in so doing, expand out on something its explanation points to.

During the Provisional Irish Republican Army’s campaign in the 1970s-90s, many Irish academics, journalists and intellectuals set about delegitimising the IRA’s claims and narratives about the history of armed independence struggles in Ireland by attacking its ideological roots and foundations. Deconstructing and demythologising Pearse was one cornerstone of this effort. The liberal intelligentsia in Ireland regard him as maniac obsessed with blood sacrifice and a fanatical reactionary. A biography of Robert Emmet by Marianne Elliot makes the claim that Pearse had necrophilic fantasies about the quartered corpse of Emmet. In her 1977 biography, Ruth Dudley Edwards first raised the stink of insinuation that Pearse may have been a pederast (1977 was a time when such a thing might be considered a character flaw.) The evidence presented is Pearse’s poem ‘The lad of the tricks’. The poem indeed will delight the eye of the queer theoretician, but the stickiness of the slur depends for its traction on the same enigma of Pearse that it intends to sully. Not enough is known about him to say so for sure. But the arrow of evidence points in the other direction.

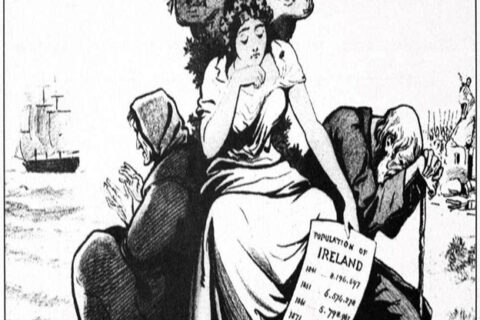

Pearse was for certain a romantic and an adherent of the Victorian cult of boyhood. He opened a boarding school for boys in 1908 with the slogan ‘an educational adventure’. He set out his ideas for root and branch educational reform in his essay ‘The murder machine’ in which he heavily criticized the English education system. It seems implausible that he would seek to institute the English public schooling’s signature feature in his own. In his essay ‘To the boys of Ireland’ he promised one day soon to arm and train Na Fianna Éireann, the Irish nationalist youth movement of which he was the leader. His writings on the romance of Robert Emmet and Sarah Curran, though chaste and innocent, are none the less red-blooded. As remarkable as it may seem, Irish Catholics – men and women – in the decades after the Famine were known for unimpeachable chastity. Births out of wedlock and marital infidelity were very uncommon. Genteel ladies of the house in America and England accordingly sought out Irish girls as domestic servants. A celibate, unmarried man was not an odd thing and the oddness of it is in the eye of the modern. Pearse, a devout Catholic, was a volcel.

To the reader familiar with what Pearse’s contemporaries had to say about him, ‘The lad of the tricks’ is immediately recognizable for what it is. In short, Pearse was neuro-atypical. Colleagues remarked on his social awkwardness, ill-judged pranks, immaturity and given to delight in pointlessly annoying and upsetting others. The poem is deliberate cringe posting to wind people up. In their book Unstoppable Brilliance, authors Michael Fitzgerald and Antoinette Walker lay out a persuasive case that Pearse had Asperger’s syndrome. Whatever its nature, this neuro-atypicality also afforded him an unusual and particular power of insight.

The Irish literary revival in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries brought about a very vibrant and important theatre scene that cross pollinated with the Gaelic revival, nationalism and a new national consciousness. The stage of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin was a forge for a new assertion of identity and early twentieth century Irish nationalism was strongly influenced not just by the content of the plays buy by dramatic structure itself.

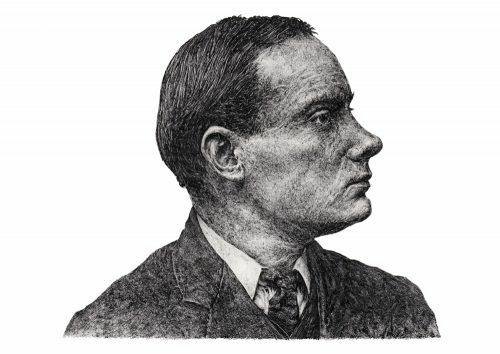

In 1915, Pearse, himself a playwright, delivered a famous oration at the funeral in Dublin of the Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. In the picture above, Pearse can be seen in his Irish National Volunteers uniform and carrying his officer’s sabre, priming the public for its theatrical surrender, which he already had in mind.

The Easter Rising of 1916 was a plot hatched by members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, including Pearse, who had taken over leadership positions in the Irish National Volunteers. The IRB expected military failure but Pearse had designed it as a kind of live ammunition street theatre with the General Post Office in Dublin, an indefensible position, as its stage as a way to win independence metapolitically. It was in part a passion play, a medieval mystery play, and an Aisling poem. A one act drama with a narrative structure and memetic and archetypal content that paralleled Catholicism so structured as to activate the ‘risen people’ that Pearse warned of. In his writings, echoed in the Proclamation of the Republic he read out as the Volunteers occupied the General Post Office, he likens the tradition of armed uprisings in Ireland handed down from the United Irishmen in 1798 to Robert Emmet in 1803, the Young Irelanders in 1848 to the Fenian Uprising of 1867 to Apostolic succession. He invoked the imagery of the Resurrection for national independence. Pearse appears to have grasped something of the idea of the archetype two decades before it was described by Jung. He identified the archetypal structure of the Irish psyche and coded a program to run on it. Or, the Irish Catholic psyche at least.

In 1916, Irish mothers were receiving letters informing them of the deaths of their sons in France, Belgium and elsewhere. Fathers scoured newspapers for casualty notices. There was no conscription in Ireland for the British Army during World War I. When Pearse, Clarke, Connolly and the Volunteers and members of the Irish Citizens Army, disarmed of their German rifles, were marched away following the surrender, the people of Dublin spat at them (and then proceeded to loot everything in the city but the bookshops). They were resented for causing the British to impose martial law and reducing Dublin’s main thoroughfare and its environs to rubble. As foreseen by Pearse, public opinion shifted as soon as the signatories of the proclamation were court martialled and shot by firing squad. Things then changed, changed utterly in the words of W.B. Yeats when James Connolly, IRB member, Labour Party founder and leader of the Irish Citizens Army (essentially, the Labour Party’s militia), mortally wounded in the fighting, was ambulanced away from his hospital bed, tied to a chair and shot by firing squad. Connolly was probably the most publicly well-known of the Rising’s leaders. Is it too much to speculate that Pearse factored his death into his scheme?

Pearse the man had no theory of republican government. He had no great insights into economics or international relations or social policy. He was a modest educator and writer who would otherwise have no great role to play in the future he envisaged. In becoming Pearse the myth, it is not too much to say that he changed future.

-By Irish Anon

O I’m a good old rebel, now that’s just what I am. For this “fair land of freedom” I do not care at all. I’m glad I fit against it, I only wish we’d won, And I don’t want no pardon for anything I done.

thanks for some insight into a little known figure

Not little known in Ireland.

The Irish understand this, the (((Norman))) not so much: http://www.occidentaldissent.com/2020/07/15/what-is-critical-theory/

Enjoyable read, thank you.