The reasons for the defeat of the CSA in the War of Northern Aggression are still hotly contested to this day. It is without a doubt, however, that recognition of the CSA by Britain and France and material support in both supplies and military arms could have made for a starkly different outcome. It was, after all, a serious issue for the CSA that they lacked the manufacturing base and resources to contend with the behemoth that was the Union. The Confederacy made early overtures to remedy this deficiency by trying to draw in Britain and France on the side of the Confederacy.

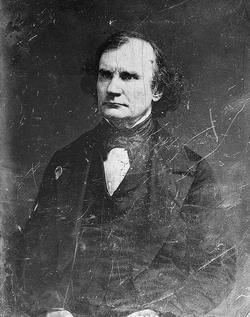

Secretary of State Robert Toombs tasked the fire-eater William Yancey with these diplomatic efforts on March 16, 1861. He was to convince the British of the righteousness of the cause and of the importance of the cotton trade on which British textiles depended. Yancey was only able to get an informal meeting with then Secretary of State Lord John Russell, the result of which was the recognition of the Confederacy as a belligerent. During this meeting, Yancey was specifially asked whether they intended to re-open the African slave trade. British policy was stauchly against the slave trade, having abolished slavery in Britain in 1833. Yancey denied that the Confederacy had any intentions to do so.

The result of this attempted diplomacy was a far cry from what Jefferson Davis had hoped for. He was convinced, like many Southern leaders, that the blockade of Southern ports was actually a positive since it would put pressure on Britain to take the Confederacy’s side in order to keep the cotton flowing into British textile mills. Before abdicating his position, Yancey made one further attempt to garner British and French support following the victory at First Manassas. Lord Russell insisted the communication be made in writing and again rebuffed Yancey, declaring that Britain would remain neutral. Yancey was disheartened by the failure, and he stated “Anti-slavery sentiment is universal. Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been read and believed.”

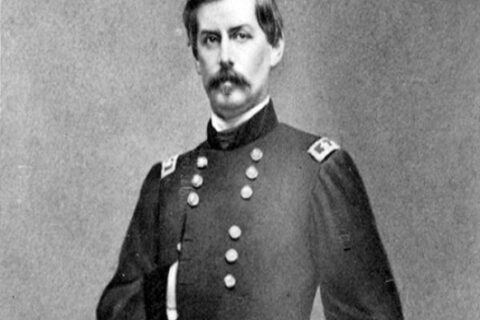

The hope of foreign intervention was dubious when William Yancey was replaced in his diplomatic capacity by the duo of James Mason and John Slidell. Mason was a respected senator from Virginia who had drafted the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and been chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Slidell was a lawyer and state politician from New Orleans who was appointed as negotiator at the end of the Mexican-American war. He would be the envoy to France where it was hoped that his command of the French language would prove more efficacious in cajoling Edouard Thouvenal and his master Napoleon III. The pair set out for Britain on the British packet ship the RMS Trent only to be pursued by Charles Wilkes of the USS San Jacinto. The Trent was stopped on November 8, 1861 and despite the protestations of its captain, the two were taken prisoner by Wilkes.

The immediate reactions to the event were varied among the major players involved. The Confederacy was elated that the Union had made what looked like a grave error. One of their officers had stopped, by force, the ship of a proud sovereign nation and molested its passengers. The Confederacy believed this would lead to recognition by the British and military support. The British were furious at this outrage. The Prime Minister Lord Palmerston was particularly livid. He was intent on delivering an ultimatum to Secretary of State William Seward. The ultimatum demanded the release of the prisoners and an apology. Relations between Seward and the British government were already stretched thin. The British ambassador to the United States, Lord Richard Lyons, had warned that Seward would threaten war to attain political capital. In a more humorous quote on Seward, Lord Clarendon said that Seward was “trying to provoke us into a quarrel and finding that it could not be affected at Washington, he was determined to compass it at sea.”

Indeed, Seward had drafted a letter to Charles Adams, Union ambassador to Britain, to be shared with the British. The letter threatened war if the British formally recognized the Confederacy. Lincoln had Adams soften the words in the letter. Like with this letter, Prince Albert softened Palmerstons ultimatum. It now only asked for an apology and that the captives be set free. Despite most citizens of the Union heartily approving of Wilkes’ actions, Seward and Lincoln acquiesced to the request. The apology was issued, and they disavowed the actions of Wilkes, saying he acted without consent. Mason and Slidell were set free and allowed to continue on their diplomatic mission.

The Trent Affair would be the closest the Confederacy ever got to obtaining help from Britain or France. All the momentum towards the intercession was finally and forever lost in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam. It was a strategic loss for the Confederacy and was followed up with the Emancipation Proclamation. The complexion of the conflict was now being conflated with a war for the abolition of slavery. The anti-slavery sentiment that Yancey had lamented had come home to roost. The Quakers’ anti-slavery propaganda had inundated the minds of the British people for years now. The Somerset Case and the writings of Anthony Benezet had fundamentally changed how the British populace viewed the issue. The Quakers, more than any group, were responsible for the failure of Confederate diplomacy.

-By Dixie Anon

O I’m a good old rebel, now that’s just what I am. For this “fair land of freedom” I do not care at all. I’m glad I fit against it, I only wish we’d won, And I don’t want no pardon for anything I done.