When I was a boy, my brother and I would finish our chores as quickly as possible on a Saturday morning. By 9 AM, we would walk about a mile to a large grass field in front of an old, dilapidated motel off of Maricamp Road (RT 464) in Central Florida. In my hand was a football that was too big for me. It was my Christmas gift from the preceding year – the only thing on my Christmas list that year. In June, school was out in Florida. The temperature was in the mid-nineties by late morning. You could smell the humidity. We didn’t care.

At the field of battle, we would meet about a dozen other boys from the area – all of whom had done the same as we did. Our scrawny nine year old bodies in tee shirts and shorts would select two team captains. I was usually one of them and as such, I felt compelled to pick my little brother, even if he sucked. After all, we were there to win but he was kin.

Among the thickets and crickets, we played tackle football. We did not use pads. Two boys formed the offensive line. They faced off against two other boys, one of whom counted five seconds before they made their attack. “One Mississippi… two Mississippi… three…” – the count could be heard through the echo of the ruins of a 1950s motel. We hit each other. We shoved each other. We got cut up and compared war wounds.

Girls would eventually show up, but they did not play. They just stood on the sidelines, giggling and looking stupid. After all, they were girls and we were playing a man’s game.

Once we reached some arbitrary number that meant the first game was concluded, we ran across the busy road to some old lady’s house and raided her water hose. We would all take a swallow before she’d come out yelling at us. No one knew what a bottle of water even was.

By about noon, the black boys would show up. We did not know them personally. They went to different schools, different churches, and different restaurants. This was the very early 80s. We were only a generation removed from segregation and back then, the majority of the South still self-segregated. Yet, here we were and they would challenge us to a game. Challenge accepted.

We played for pride. We hit them a little harder. They hit us back a little harder. We took chances, broke tackles, threw the ball further, and played our hearts out. Sometimes they would win. Sometimes we would win. One thing was certain: when it came time to raid a water hose, they did not go near the old white lady’s home.

When Fall came around, we played football throughout the year in the same way until the mid-80s when Pop Warner finally made its way to us. In Florida, football was not just a passion; it was a way into college. We all knew our role as players. The speedy black boys were running backs and wide receivers. The receivers, who couldn’t catch, were safeties and corners. Meanwhile, the big white boys – such as myself – were on the line. The other white boys were quarterbacks, fullbacks, or middle linebackers. None of us could care less. We just wanted to play and we played hard.

When I was thirteen years old and moved to Queens, New York, I quickly learned the difference between the South and the North playing football. At my first practice as a linebacker, I broke the quarterback’s nose and rendered him unconscious. I never seen such soft line play in my life. The QB was a Jewish boy with an exceedingly large nose and a perfectly coiffed afro. His mother was on the sidelines at practice with a professional photographer (an oddity to me). I had never met a Jewish boy prior to moving to Queens. More importantly, I had never met a Jewish mother. She screamed and hollered at the coach, an Italian-American gym teacher. How dare you let my son get hurt like that… it is just a game! I was tossed off the team for being too aggressive, although I think her threat of a lawsuit played a factor.

I played again in my sophomore year, but it wasn’t the same. Two-hand touch was a popular game up North; such a peculiar people. By the time I was sixteen years old, I discovered girls were not so stupid after all. Yankee football was. After my junior year, I stopped playing until I went into the Marine Corps.

Still, I loved the game.

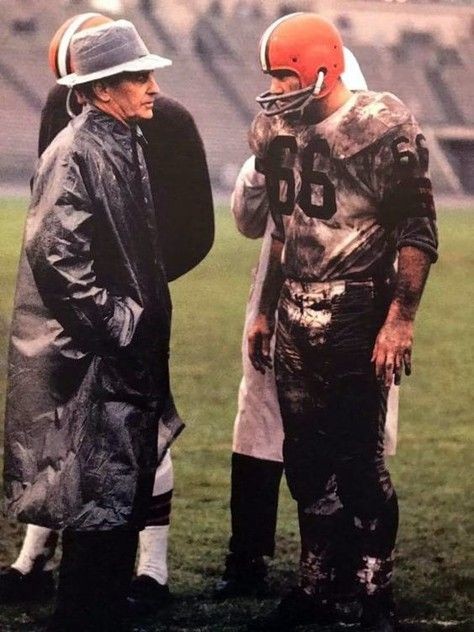

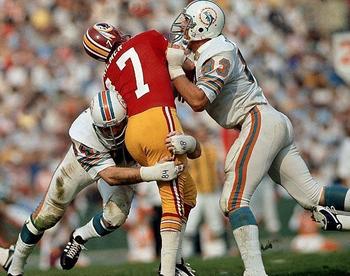

I loved the strategy of the sport. The tests of masculine strength, enduring bitter cold temperatures, torrential rain, and intense pain. I watched games for the subtle clues on a play. I watched for the thrill of a last second field goal or a Hail Mary pass. Football was a battle between men led by generals.

The music and drama behind NFL Films were always exciting to watch. There was a militancy about them. Drums would play in the background and exciting music would lead the viewer into the story line. John Facenda’s voice was masculine and dramatic. Steve Sabol’s films captured the billowing steams of breath from the sidelines. Men with broken bones, bloody faces, and missing teeth were depicted leaving the field, often on a stretcher. Other men replaced them, like soldiers moving in to replace lost comrades in the trenches.

College football was just as exciting, but different. It was a faster sport. There was almost a whimsical feeling about college football, with their smoking hot cheerleaders and entire schools doing a Gator chop, a “Dawgs” bark, or whatever the Carolina Cocks do. Watching an entire stadium sing “Rocky Top” while decked out in orange is an indescribable moment of unity for a people.

For years I watched football religiously; perhaps too religiously. When the NFL kneeling protests began, I was not so much upset with disrespecting the anthem, per se. By then, I had lost my taste for the Empire. Rather, it was a signal to the world: the relationship between employee and employer flipped, as did Black and White. As a life-long customer of football, this player was not only kneeling out of some pathetic Marxist perspective on justifiable police shootings, he was telling me I was bad for being White. Worse, he was telling his employers that he did not have to respect their clients – the predominantly conservative, White male viewer.

When fellow White men tried to justify kneeling as a “first amendment right,” I had to frequently remind them that no employee has the right to protest during work. The mental gymnastics required by White men to justify Black ball players protesting a flag and an anthem was a massive wake up call. These White men cared nothing for the Nation they had built, as long as a someone could run really fast. One fellow veteran on a VFW thread wrote, “I fought two tours in Vietnam for his right to protest!” As if the Vietcong would have denied a coddled ballplayer the right to protest America on Marxist grounds.

It was a clear sign as to how far we had fallen.

Even after losing fans and revenue, the NFL continued to justify the behavior of arrogant and disrespectful football players. At the time, the NFL’s response – allow them to keep protesting – shocked me, but it should not have. Like many former football fans, I failed to see the warning signs.

Female viewership was all too important, so the game was getting less violent. Breast cancer awareness, although a worthy cause, seemed an odd choice when nearly twenty-five percent of the NFL’s viewership were statistically likely to suffer from prostate cancer. The shift to female fans coincided with a series of lawsuits aimed at concussions. This led to rules changes ostensibly for safety reasons.

Personally, I think the soft shift to attract females is a mistake, decided upon by soy boy marketing teams in New York. Women are genetically attracted to acts of masculine strength and grit. But I digress.

If you watched the 1991 Super Bowl with jets flying overhead while men (me among them) headed off to the Gulf War, you would see how different the sport has become. It was all about Americana. Whitney Houston sang a stunning rendition of the Star Spangled Banner. Lee Greenwood sang “God Bless the USA” at the halftime show. Less than thirty years ago the NFL was the epitome of masculine militancy. Last year, the halftime show was about transgender rights and Black power.

The NFL has become a pathetic shell of its former glorious, militant self.

Because I know how far the NFL has fallen, I no longer watch the sport. I reckon it would be much like watching your son turn gay. You love the boy, but you sure do not support that sinful nonsense – it makes you sad to watch. It is a tragic reminder of the degraded condition of the United States.

Anyway, thank God the South still has college football. There is perhaps no other sport that is so dominated by the South as much as college football. Long after the NFL transitions to a two hand touch league, Southern teams will continue playing the sport I love.

Auburn and Alabama will still divide families on a Saturday in Birmingham. Gator fans and Georgia fans will drink their faces off in Jacksonville on the final weekend of October. LSU fans will wax philosophical about the sport, but no one will understand what the hell their Coonasses are saying. Ole Miss will still have the hottest cheerleaders in the country, even if they cannot win a game.

Just like religion: long after the Yankees have abandoned the institution, it will remain strong in the South.

Go Dawgs!

The son of a recent Irish immigrant and another with roots to Virginia since 1670. I love both my Irish and Southern Nations with a passion. Florida will always be my country. Dissident support here: Padraig Martin is Dixie on the Rocks (buymeacoffee.com)

I stopped watching NFL games years ago as I find the players don’t much look like me. Too many LaDarian’s and Daquans…

I have always been, and remain to this day, an avid H.S. football fan. I began playing “backyard” tackle football as a little boy of only eight or nine years old. I signed up to play peewee football as a fourth grader, and played every year afterward through H.S. I have always said that football was the only thing that kept me in school after my freshman year, since I could see little benefit to what I was being taught in my public school thereinafter. The “brotherhood” and comaradarie developed as a member of our football team was the best thing I ever received from attending public school, and of course it kept me in tip-top shape as well since I was not an especially talented athlete but was extremely conscientious about being the best player and biggest asset to my team I possibly could be; and those relationships developed with my teammates so long ago have for the most part withstood the test of time.

As far as professional and college football goes, with BRPeterson above, I gave up on Pro Football many moons ago, back in the early ’90s. I could see where the sport was headed and lost interest shortly thereafter, and have never looked back. It took me a little longer to essentially abandon college football; I still watch a game now and again, but not very often. I just have no real interest in it other than that I know a few major college players and their families. But on Friday nights from late August to early December I and my boys are easy to find if you’re looking for us. Ha!

Ah yes, high school ball, the unadulterated sport, truly nothing is more fulfilling than watching your son playing at the Friday night game or your daughter in the cheer squad!