Broadly speaking, and at the risk of some oversimplification, American exploitation filmmakers from the early 1950s to the early 1990s can be placed in three categories based on geography:

- Southern California: generally defined by bigger budgets, most of the actors are recognizable by fans.

- New York City: the budgets are significantly smaller, and the films typically have a far grittier look. A few of the actors may be recognizable, but for the most part the actors are unknown.

- Everything else, the regional scene: these films almost exist in their own world, the budgets are all significantly smaller, and with certain rare exceptions, the cast is almost completely unknown with the director employing his friends and locals being commonplace.

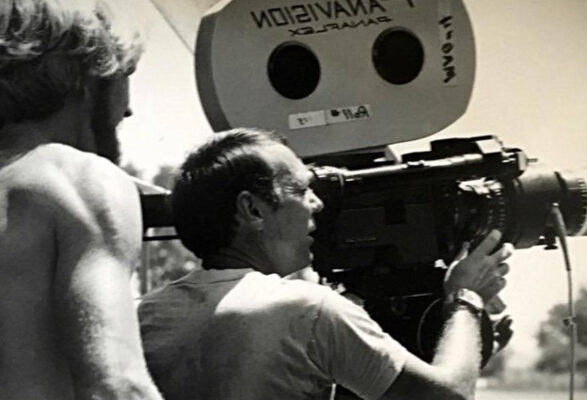

As a tradeoff for the smaller budgets, the regional scene tends to be dominated by mavericks with far stranger visions, and, because of that, their films almost exist in their own universe. They have the topics their interested in, and they are determined to present them on film, being more than willing to work well outside any kind of studio system for this level of artistic freedom. Charles B. Pierce clearly fits well within this regional tradition of filmmaking. He loved Arkansas and wanted to tell Arkansan stories, to tell these stories he was willing to take a sever pay cut, and for that I admire him. The man had technical skill, even when working with a micro-budget. He could have gone to California earlier in his career and become a stable, reliable workhorse. But he never did that, until he was all but forced to, because Arkansas meant more to him.

Sadly, Pierce would be one of the last of the regional exploitation filmmakers. When he started his career in the early 1970s, most movie theaters, and especially the drive-ins in which his films thrived, were independently and locally owned and could be geared more toward local tastes. But by the mid-1980s, this was quickly drying up. Gone were the local theaters, they were being replaced with multiplexes run by giant corporations, and, as such, local tastes were taken less and less into account. For someone embedded in his region, as Pierce was, this was a deathblow. Big budget movies, now opening nationally rather than hitting a few regions at a time, became the standard and Pierce, and those like him, could not compete.

While many of his likeminded filmmakers were able to gain a new career thanks to home video, at least temporarily, Pierce was unable to do that. The Legend of Boggy Creek, though widely available, was also plagued by the vast majority of copies being of incredibly poor quality. The Town That Dreaded Sundown would only see limited releases on video. And those were two of his most widely seen films during the video era – two of his other best films, Bootleggers and The Evictors, were even more rarely seen. But, in the end, even had he been able to transition to the video era more successfully, it would have only been temporarily, as the same forces that destroyed the local theaters were also consuming local video stores that gave some of his fellow travelers a new lease on life. In the 1980s, video stores had been independently owned and would cater to more offbeat tastes; by the mid-1990s, Blockbuster had taken over, and much like the similar corporate takeover of the theaters a decade earlier, the offerings became much more gentrified. There was simply no longer a place for someone like Pierce.

Although hardly a household name, save for the Texarkana area, Charles B. Pierce left a profound mark on the art of cinema that far too few appreciate. His pseudo-documentary style helped anticipate an entire style of filmmaking that has made a major impact on the medium, especially in the past 30 years. But more than that, his love of Arkansas should be remembered, especially by Dixian Nationalists. It’s clear he loved his land and her people, and wanted to tell their stories in a manner Hollywood would not do. There will never be anything like the daring landscape of 1970s cinema, it’s far too sanitized and risk-adverse now, with Hollywood preferring to tell the umpteenth Marvel movie rather than to take the risks common back then. And there will never be someone like Charles B. Pierce again, and for the world of cinema, and especially Dixie, we’re worse off because of it.

Let’s add music to film!

The French band Asylum Party: The song Julia !

Art Rock with Dixie!

Never say never; one does not know what God’s Grace in cooperation with man’s good will holds in store.

Nice series of Articles!

Thanks staff at I.D.