I have a long-time, on again-off again, love affair with aviation that I inherited from my father. I haven’t been in the cockpit of an airplane in a number of years now, but at one time in the not-too-distant past, flying was a favorite pastime of mine that I indulged as often as I could, and enjoyed immensely. I’ve been seriously considering getting back into it and getting current again.

When I was about fifteen or sixteen years-old, my dad purchased a used hang-glider he found for sale in one of those old auto-trader magazines that were popular before Al Gore invented the internet. For several months afterward, my dad and I (along with a couple of my elder cousins on several occasions) would occupy a portion of our free time learning to fly and maneuver our newly-acquired craft. We started out simple and small, running it down pond dams and gradual inclines on hilly country roads, that sort of thing. There were a number of minor mishaps involved, but the better we got at maneuvering our craft, the more emboldened we became to test our skills on higher hills and steeper grades.

One of my now deceased uncles owned property that connects to the north bank of the Red River. Perhaps a half of a mile north of the river is a natural, almost vertical bluff (“The Bluff”) overlooking bottom land that we call the pecan bottom. The bluff is perhaps 125-150 ft in height, and it was our goal, from day one, to fly the hang-glider off the edge of the bluff, and maneuver it safely to the ground at some point at the edge of the pecan bottom. This was my particular desire; my dad, not s’much.

I literally begged my dad on several occasions to let me fulfill that goal, but he never felt comfortable with the idea, and therefore would not consent to it. My dad rightly understood that, to ready ourselves for the dynamics we would be experiencing by virtue of flying off of a vertical cliff vs. gaining a little air down a gently sloping hillside, we would need to put more distance between us and the ground, and learn thereby to better control the glider in extended periods of actual flight. In order to gain that invaluable experience, my dad got the ingenious idea to procure 200 ft of rope and the assistance of half a dozen grown men.

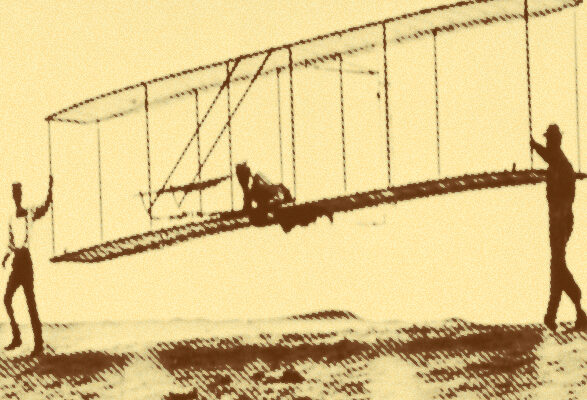

This was real Wilbur & Orville Wright stuff we were up to. Difference being that we weren’t in Kitty Hawk, NC conducting our trials, nor had my dad and I bothered to gain any real insight into the basic principles of flying, nor of flight dynamics. We were just “winging it,” in a manner of speaking, and literally “flying by the seats of our pants.”

My dad took the first ride behind the rope, and, to this day, I have never personally witnessed a more perfectly executed flight, from 0 to roughly 30’ agl, and back to the ground in a straight line of flight. Next was my turn, and my dad’s previous success was all I needed to vanquish any and all doubts I might have previously entertained of my ride ending badly. However, we all agreed that 30 ft agl was only a third of the altitude we needed to achieve for our purposes, so we quickly devised a plan for making up the deficit.

Instead of a half a dozen men supplying the “motive power” at the other end of the rope, we decided it would be better and more efficient all around to put the horses under the hood of my dad’s pickup to the task. The scheme agreed to was that my dad would operate the pickup, while another man would establish a firm seat in its bed holding the rope. It was understood that either of us could let go of his end of the rope at any time during the flight. Here is where this entire scheme of ours began to go horribly wrong.

When the ready signal was given by yours truly, a couple of unexpected things occurred in rapid succession: first, my dad inadvertently accelerated too suddenly, and, secondly, nature determined to throw a gust of wind in our faces at that exact moment. Those two factors resulted in a higher angle of attack than I had originally put the nose of the glider into, resulting in a much swifter climb rate and gain in altitude than anyone expected. The glider literally went from 0 to 150 ft, almost at the zenith of my dad’s pickup, in a matter of about three second’s time. This caused the guy in the bed of the pickup to panic and let go of his end of the rope, which instantly countermanded my attempts to get the nose down and threw the glider into a stall. What followed for the next few seconds would be nothing more than a fuzzy memory for all, had there not been a level-headed witness and fellow aviation enthusiast named Ray Porterfield on the ground who later described the whole incident in minute detail, start to finish.

I have a good friend I’ve known for many years who, at one time, shared my interest in airplanes and flying, although he’d never ridden in a single-engine airplane. One day, I invited my friend to go flying with me, which invitation he eagerly accepted. I picked a day forecast to be clear and calm simply because I desperately wanted my friend to have a pleasant first experience in a single engine airplane.

When we took off, the day was clear and calm as expected; however, an hour and a half later when we got into the landing pattern at our local airport, the wind had picked up to around 12 knots, direct crosswind. Nothing to be alarmed by or anything, but the wind conditions did force me to put the airplane into a slip-to-land maneuver on final approach to keep our glide path aligned with the centerline of the runway. I could tell the configuration I had the plane in was unnerving for my friend to say the least, so I kept reassuring him that this was just normal stuff in such conditions, and that I would get us on the ground safely.

Not only did I get us down safely, but I performed what you might say was a textbook example of a slip-to-land maneuver in that instance. I was actually quite proud of my performance, but my friend was not in the least impressed and demanded of me to, “let me out of this bleeper bleeper right bleeping now!” So I taxied off the runway and let him out, then went back to perform a few touch and gos, since the conditions were perfect to safely practice the maneuver, and it was a maneuver I never missed an opportunity to practice, for the simple reason that I understood that being proficient at performing it under worse conditions would likely save my ass, as well as the airplane, later down the road. A lesson I’d learned the hard way as a fifteen year-old.

I saw my friend above-mentioned for the first time in several years a few months ago. Among other things we talked about in that reunion, was the flying incident now roughly twenty years behind us. I asked my friend how much flying, if any, he had done in the meantime, and his answer came as a bit of a surprise to me. He said that his “flying days” ended at the moment the wheels touched down the one and only time he rode with me way back when. I’d heard about stuff like that before; my flight instructor once told me of an incident when a former student of his was on his first solo flight to another airport sixty miles distant. He miscorrected for ground effect on landing, which resulted in something of a “hard landing.” Hard enough to give him a good jolt, but not hard enough to damage the airplane. Whereupon, he nervously taxied the airplane to the terminal, buckled it down, and called a family member to come pick him up, later informing his instructor that he would never fly again due to that incident.

When I was taking flying lessons, it rapidly became crystal clear to me what had gone wrong during my flight of the phoenix as a fifteen year-old, some twenty-plus years earlier. Practicing stall recoveries is a requirement in private pilot training. Practicing secondary stalls is another requirement, but I’m pretty sure the time spent on secondary stall recovery is less than that required for primary stalls.

Anyway, secondary stalls are far more violent and require a higher degree of piloting skill to recover from than primary stalls. Secondary stalls result from overcorrecting in the immediate aftermath of a primary stall, and this is precisely what happened, according to Ray Porterfield’s account of the hang gliding incident mentioned above. I initially overcorrected for the primary stall, thrusting the glider into a secondary stall situation, and immediately thereafter into an irrecoverable spiral to the ground.

The glider and I hit the ground with such force that the triangular aluminum bar on the craft was bent at a ninety degree angle just below where my hands had tightly grasped it throughout the flight. The impact “knocked me silly” initially, and I distinctly remember coming to moments later, thinking to myself that I must be dead, that I could not have possibly survived this crash. Within a matter of seconds, reality set in and I knew I had in fact survived. The pain from my injuries incurred was the first clue I was in fact alive. When all was said and done, neither the pain, nor the injuries themselves, were terribly serious, miraculously. My nose was busted and bleeding profusely, and there were some pretty deep scrapes and gouges on my hands and legs, as well as a lot of deep bruising and soreness that came afterward, but that was about it.

During the reunion with my old friend, I was showing him photos on my phone of some of my battle scars I had received a week or so before in a paintball war between all but two of my kids and me and members of a few of their families equally divided into two opposing teams. My friend looked upon those wounds in horror, pronouncing that that was the very reason he had never, nor ever would, do the paintball thing. This came as a disappointment to me, since we had already decided to play again a month later, and I wanted my friend to participate with us. I went ahead and asked, but he flatly refused, citing his low tolerance for pain and the fear it instills in him.

Don’t get me wrong, y’all, I’m no thrill-seeker, and I’m certainly not in the habit of knowingly putting myself or anyone else in precarious situations that have a high probability of resulting in life altering consequences or even death. When the word “phobia” and its derivatives actually described irrational fear of a thing or things that is nonetheless real, I might have applied the term to my friend’s fear of flying and of the pain associated with being hit with a paintball coming in at high velocity. As it stands now, however, the term is rendered mostly meaningless by virtue of the fact that it’s been hijacked by the Left and their lunatic ideas.

If Doug White had succumbed to the fear-inducing situation fate suddenly thrust him into on Easter Sunday, 2009, he and his family would not be here today to inspire us with their story. Nor, I daresay, would Mr. White himself now be the man that he is in the eyes of his family and his broader circle of admirers had he not cast aside fear and focused like a laser beam on the daunting task before him on that fateful day. I believe that if Mr. White were to read this article, he would gladly second me in proclaiming that living in fear is no way to live.

God bless the Southland.

I share your love of flying, though not all your wonderful experiences! I grew up during Project Mercury and of course wanted to be an astronaut. I’m too old today for skydiving or hang-gliding (a man’s got to know his limitations … and the diminished flexibility in his bones), but love reading the accounts of famous aviators like ‘Inside the Baron’ and Rudel’s ‘Stuka Pilot’.

Great story Mr. Morris.

I too, had grown up with a Southern pilot Father, I was with him In a Cessna when he stalled the aircraft right over pearl harbor! Unannounced to me, straight down, I grabbed the passenger steering with all my 5 year old might, I don’t know how he leveled it off.

Ashamed to say, I ended my flying career with chicken wings first class, even though I flew with him on many more Cessna’s and gliders after that.

He later took us to kittyhawk, I have walked those dunes.

God Bless You Sir, and God Bless the Southland.

I love this!

Interesting story. Glad you lived to tell it!