Post-Redemption Dixie, and greater America, experienced a significant shift in politics as well as the means through which laymen asserted their will. Jeffersonian Idealism permeated primarily within the Southern United States and tended to assert itself in more agrarian regions. Lasting in its truest form until the Presidential Election of 1896, the philosophy ended with quite a loud roar, instead of a whimper. Defining much of Southern and agrarian political thought during much of the 19th century, Jeffersonian Democracy experienced a period of repeated attacks against it politically and physically as well as a later revival which culminated in the alliance of various political movements. Instead of defining Jeffersonian beliefs themselves, this essay will detail the final moments of the philosophy in the mainstream, addressing the War Between the States and its aftermath as well as the various populist movements, called the Farmers’ Movement, which culminated in the eventful election of 1896.

The War for Southern Independence, at its core, addressed the feud between the republican Jeffersionian ideals of the First Republic and that of the memetic descendant of the combined Northern philosophies such as Puritanism, Fourty-Eighter German socialist idealism, industrialism, and Hamiltonianism. The society which adopted this method of thinking was utterly obliterated by the War and had to rebuild itself. The Redeemers of the South, as they were called, consisted of the former wealthy Planters who tended to hold moderate Bourbon Democrat views and displayed little interest in addressing the woes of poor farmers, with the exception of the issues which would bestow these Bourbons additional political capital. Many even endorsed the urban economic idealism of the New South.

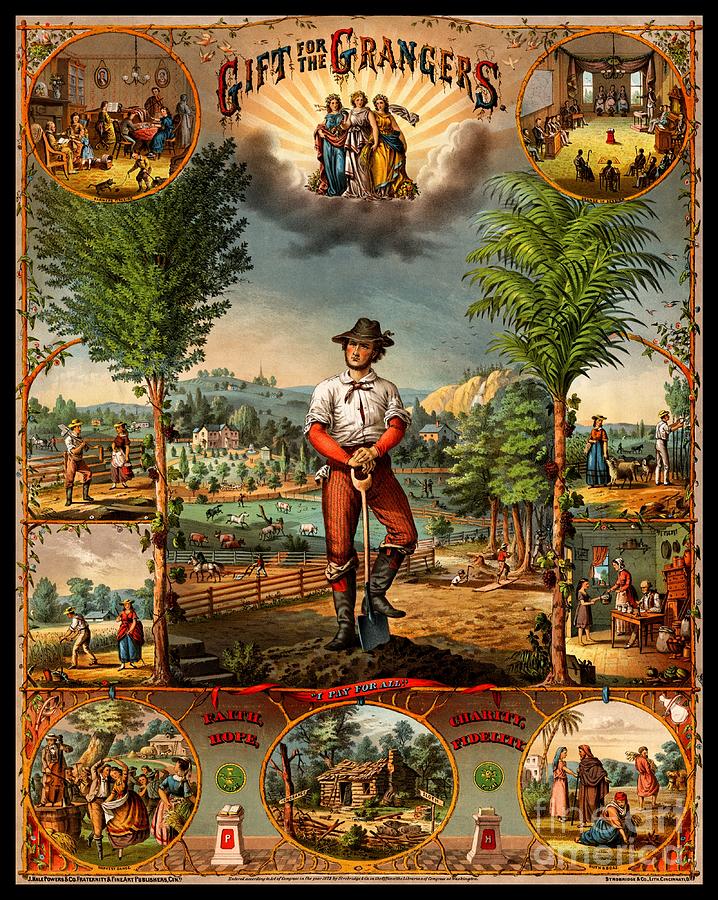

As a reaction against this, farmers very early in Reconstruction began forming means of organizing against neglect. The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry formed in 1867 and sought to represent these poor folk during Reconstruction. This began a slow wave of agrarian political activism among the lower classes which grew rapidly during the 1870’s and 1880’s. The Grangers managed to achieve a great deal of success and grew to a large size across the South and Midwest and even achieved the goal of having the Granger Laws passed.

The Farmers’ Alliance, much like The Grange, formed a large political movement intent on supporting poor farmers. Unlike The Grange, the movement consisted of a coalition of alliances in different regions of the country which organized relative to the socio-cultural aspects of their respective societies, instead of a single fraternal group. There were 3 major regional groups which formed the movement: the National Farmers’ Alliance, the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union, and the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Cooperative Union.

In 1877, a group of Grangers in New York state founded the National Farmers’ Alliance, more commonly known as the Northern Alliance. This group ultimately failed in its ambitions but did experience a revival of sorts in 1880 in Chicago when a new group was established by newspaper editor Milton George. George utilized his newpaper, Western Rural, to great effect in spreading the Alliance’s message and attracting members. The Alliance proved popular in the western half of the Midwest; whereas the more prosperous states of Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan gave little support. Rapid expansion and the population explosion of the western parts of the country defined the group’s motives. This Alliance sought to protect farmers from monopolies, pass various tax laws, regulate interstate commerce, and abolish free travel passes to public officials. Despite initial attendance success, prosperity returned to agriculture in 1883 which rendered the organization totally moribund. Attendance and activism reignited in 1884 due to a collapse in wheat and livestock prices. During this time, the group continued spreading west, employed a system of dues to fund the organization, and held a 5th Convention in 1886. Additionally, its attitudes and beliefs became more radical and left-wing. Support for Free Silver, government ownership of intercontinental railroads, and an alliance with the industrial labor union group Knights of Labor came to light. The increased enthusiasm and membership drove a growing desire to assert the group’s interest through a definitive political organization.

In 1875 within Lampasas County, TX, Texas ranchers organized to prevent cattle theft, purchase large stores of supplies as a group, and round up stray animals, laying the early framework of what would later become the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union and known as the Southern Alliance. Continuing to grow in operation, the alliance nearly collapsed in 1878 due to hostile factions of the Democratic and Greenback Parties. The alliance reestablished itself in 1879 in Parker County and incorporated into the Farmers’ State Alliance in 1880, following the methods and constitution of the Northern Alliance and exploding in popularity. In 1886, Charles Macune was elected to Chairman of the Executive Committee and quickly managed to quell a fracturing of the organization by endorsing the goal of separating the alliance from its northern counterpart. In the following years, the Southern Alliance continued to expanded via mergers with other Southern organizations including the Louisiana Farmers’ Union and the Agricultural Wheel. Pursuing a similar set of demands to the Northern Alliance, the Southern Alliance supported abolition of national banks and monopolies, Free Silver, fiat money, land loans, creation of sub-treasuries, establishment of income taxes, and tariff reform. At the 1889 Convention in St. Louis, the group finally changed its name to National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union.

Despite the general lack of racialist sentiments among populists at the time, Negroes faced deliberate exclusion from the Southern Alliance. Seeking membership, blacks established their own Colored Farmers National Alliance and Cooperative Union in 1886 in Texas. Following a similar amount of demands to the other alliances, the primary focus of this group involved the downtrodden nature of poor black farmers and applied methods espoused by Booker Washington. The alliance met its demise in the early 1890’s upon aggressive pursuance of having black sharecroppers’ wages raised from 50 cents to $1 per hundred pounds of cotton. Staunch resistance to this demand led to the group’s downfall.

Synchronous to the Farmers’ Alliance and Grangers, a more direct form of political activism took place in the left-wing Greenback Party. Formed in 1874, the Greenback Party initially developed a left-wing political outlook which favored farmers in the Midwest. It also held many similarities to the Grangers and even allied with them. However, it allied with industrial labor movements as the party continued to develop. In 1889, the party had totally dissolved.

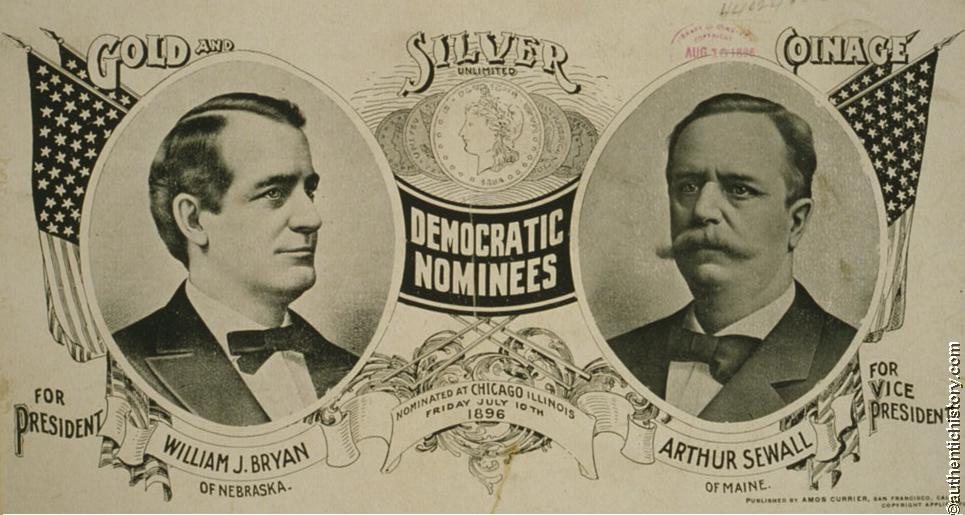

These pre-existing, and in some cases declining, movements congregated together to form the People’s Party, also known as the Populist Party, in 1892. The party amalgamated the beliefs of previous organizations and added additional stances to its platform. Generally encompassing previous positions mentioned in this essay, two notable additions to the Platform included its support of bimetallism and its calling for an amendment which allowed for the direct election of senators. Despite its widespread success for a third party, it totally collapsed following the 1896 presidential election and its nomination support of William Jennings Bryan. The party dissolved in 1908.

White Southerners rarely broke with party loyalty. As a result, the People’s Party and other major organizations involved in the populism of the time never effectively penetrated the South even though they found a decent amount of success, mostly being relegated to Appalachia. However, a concurrent populist movement infiltrated the Democratic Party in the South. Establishing a precedent for the 1896 Presidential Election, the Farmers’ Alliance and later People’s Party worked diligently to elect Democrats to public positions. The greatest success these movements achieved took place in South Carolina and led to the election of Ben Tillman to the Governorship in 1890 and later to US Senate in 1895. Though he generally worked to support the lowly farmer, he gradually moved away from his populist base with time. Additionally, successes the Southern populists secured solidified with the passage, enforcement, and expansion of Jim Crow Laws and segregation, as many poor whites tended to harbor malicious attitudes for freedmen as opposed to the more moderate former plantation masters. Generally, populism experienced a great amount of success in the South in spite of the lack of third party support.

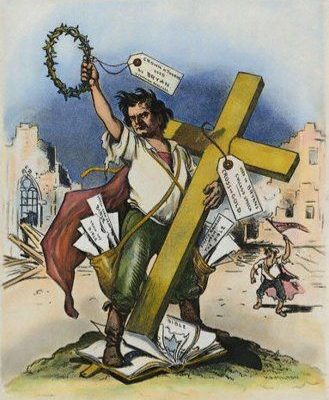

Despite the successes of the 1892 election and previous litigation, the various factions of the Populist Party and the greater movement experienced a period of infighting and discussion on the methods of proceeding forward. Utilizing the Democratic Party in the Presidential Election of 1896, twilight began to set on the days of Jeffersonian Idealism. The hotly contested election resulted in the populists nominating William Jennings Bryan to the Democratic ticket, much to the chagrin of the business friendly and wealthy Bourbon Democrats. The Bourbons long stood in opposition to the growing populism of the underclasses, and many of them split to form their own parties. Bryan’s support for agrarianism and bimetallism as well as a few other key issues received widespread acclaim in the South, Midwest, and Mountain West. William McKinley, the Republican nominee, managed to forge a coalition of businessmen, wealthy farmers, skilled factory workers, and professionals who lacked sympathy for the working classes or agrarian ideals and managed to win the intensely contested election. The outcome of the election obliterated the remains of the populist movement, but the populists continued to hold power over the Democratic Party until the 1920’s, having successfully taken power away from the Bourbons.

With that, the ideals of Jeffersonian Democracy finally ended. Agrarian populism never found the same momentum again after the election and has yet to even within contemporary politics. Though the Democratic Party housed many of these Populists after the election, the Progressives and various other political figures like Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson vehemently opposed them. The Farmers’ Movement, being constituted of the Grangers, Farmers’ Alliance, and the Populist Party, represented the final gasps of a defining piece of the Old Republic. Though a number of populist movements made attempts to assert themselves, they were memetic descendants and not truly Jeffersonian. With the adoption of fiat currency long ago and the displacement of poor farmers with Big Agriculture and third world immigrants, the days of such idealism no longer permeate within political thought, and any attempts to revive it would most certainly end with stark resistance and ultimately failure.

“The White people of the South are the greatest minority in this nation. They deserve consideration and understanding instead of the persecution of twisted propaganda.” –Strom Thurmond