“No other general in the war commanded more respect and admiration from his men than George McClellan.”

John Cannan, The Antietam Campaign

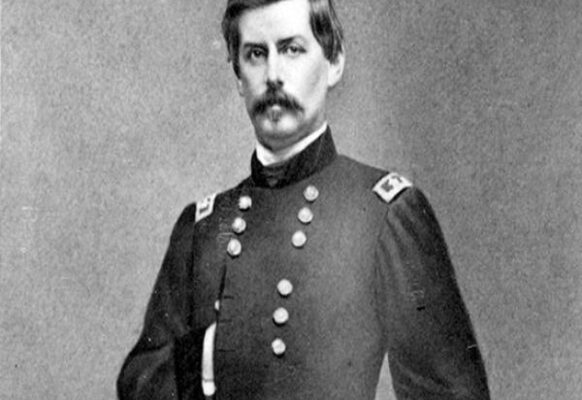

I believe General George B. McClellan was the most underrated army commander of the Civil War. While I do not consider him to be a great general or military genius, I think the common portrayal of him as a terrible commander is unjust. No other Northern general, people say, exemplifies the stereotype of an incompetent and timid leader as McClellan does. This is an unwarranted perception.

“Remember that your only foes are the armed traitors, – and show mercy even to them when they are in your power, for many of them are misguided” and later “Bear in mind that you are in the country of friends, not of enemies, – that you are here to protect, not to destroy.”

George B McClellan, May 26, 1861, and June 25, 1861

Northern Democrats did not see the South as the spawn of Satan but rather as fellow Americans who, in fact, had produced most of the Union leaders up to that point. General McClellan, a Democrat, held tolerant views of the South and sought to avoid needless bloodshed. These perspectives stand in contrast to those of many modern historians and the Republicans of the time, who shaped the narrative to justify the massacres that would follow, as well as the total warfare of 1864 and 1865.

West Virginia and Promotion

“Hardley six weeks had elapsed… and in that time he had actually created an army and began the first campaign.”

George B. McClellan, Commanding General U.S Army, May 26, 1861

–

George B. McClellan, nicknamed “Young Napoleon” or “Little Mac,” graduated second in his class of 59 at the U.S. Military Academy in 1846. His class included 20 future full-rank generals, and he later returned to West Point as an instructor.

After the war began, he excelled at organizing militia from three states into a cohesive fighting force and saw his first action as a commander of Union forces in what is now West Virginia. This was a departure from his later reputation as a slow-moving, timid general. During a successful campaign in the mountainous region he launched aggressive attacks, dislodged Confederate forces, and captured key positions. He forced the retreat of Confederate troops fortified in the mountain terrain, all while taking minimal losses and securing large supply bases and many prisoners. This success helped preserve the future West Virginia for the Union and prevented the destruction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. President Lincoln was very impressed, which led to McClellan’s appointment to replace McDowell after the latter’s defeat in the Battle of First Manassas[1], and later as the commander of all Union forces.

Organization of the Army of the Potomac

“In a very real sense, McClellan rescued the Union in these early days from dependency and fear. Someone had to rebuild the army and show the country that there was great hope for the future.”

S.C. Gwynne, Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson

The nonmilitary press and President Abraham Lincoln, who was pressured for political reasons, wanted quick action and a fast end to the war. Part of what fueled this was the North’s inability (even after First Manassas) to see how determined the South was. They thought this would be a quick, easy conflict. They underestimated the South’s resolve to fight and ability to wage war. So, while the press and Lincoln called on Mac for fast action, as a military man, Mac understood that the demoralized citizen army needed discipline, training, and organization. He provided these, got rid of poorly performing generals and instilled spirit and pride in the soldiers while increasing their morale. He came to be loved and revered by his men.

One thing even those who are critical of him admit is that he was a first-rate organizer of the army. Mac took a defeated militia force and turned it into a professional army.

“McClellan had started with… a collection of undisciplined, ill-officered, and un-instructed men, who were, as a rule, much demoralized by defeat and ready to run at the first shot. He ended with the finest army ever seen on the North American continent.”

James V. Murfin, Battlefields of the Civil War

Had the North attacked before they were ready, as Lincoln and the press called for, the result would likely have been further defeats and a shattering blow to national morale. As General Sherman stated, Napoleon took three years to build an army, yet “here it’s expected in ninety days, and Bull Run is the consequence.”

Mac’s offensive plan, as called for by many in the North, was to mass a large army, some said up to 200,000 to march on Richmond and end the war. The Northern people wanted no mistakes after First Manassas. This was Mac’s general plan; one that would take time and preparation. Mac also constructed large fortifications around D.C., which had been left almost entirely unguarded by McDowell, including 48 forts and 480 guns. Given that Mac had to train, organize, recruit, and supply a massive citizen army and transform it into a world-class professional army, the time he took to do so was entirely reasonable.

“When I was placed in command of the armies of the United States, I turned my attention to the whole field of operations, regarding the army of the Potomac as only one, while the most important, of the masses under my command.”

George B. McClellan, 1861

Further, Mac was commander of all armies and planned for a simultaneous synchronized attack across the Confederacy, which would take further time to plan and put in motion. On August 4th, 1861, in a letter to Lincoln, he laid out his plan that included the main attack to be against Richmond but also simultaneously pushing into Missouri and down the Mississippi, and after Kentucky joined the Union, to push into Tennessee, seizing Nashville, and also begin capturing coastal cities such as New Orleans, Savannah and Mobile, then move onto Montgomery and Pensacola. Mac wanted one massive assault to wipe out the South and not a prolonged war; this would take time to prepare. In February 1862, he wrote to Secretary of War Stanton, saying “I have ever regarded our true policy as being that of fully preparing ourselves and then seeking for the most decisive results; – I do not wish to waste life in useless battles, but prefer to strike at the heart.” He did not want years of bloodshed to wear down the South, but brief, decisive action to end the war quickly.

Demotion by Lincoln

Just when Mac felt his army was ready, winter had started in, and Mac was bedridden for three weeks around Christmas. Lincoln wanted action now, despite the impassable roads (he would not demand Grant move this early in ‘64) and Mac was accused of being timid. This offensive action was attempted in the winter of ‘62 by Burnside, and the results were Fredericksburg and the “mud march,” which ended in Burnside’s removal. Grant, in ‘64, would start his spring offensive in April, later than Mac would his Peninsula Campaign. As Grant said, the roads in Virginia would not allow large movements of troops before then, leading William Swinton in Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac to write, “It was inevitable that the first leaders should be sacrificed to the nation’s ignorance of war.”

So, Mac started at the average time for spring offensives. No other Union army was campaigning during this winter. Yet, because of Lincoln’s urgency and what he saw as a too-cautious McClellan, he demoted Mac to simply commander of the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln also forced corps commanders he had chosen on the Army of the Potomac. Mac wanted to wait to promote generals until he had seen them in battle. This was not the last time a politician interfered with Mac’s plans.

Peninsula Campaign Begins

“Reduced my force by 1/3, after (bless and do not curse) task had been assigned, its operations planned… it frustrated all my plans… it left me incapable of continuing operations which had been begun. It made rapid and brilliant operations impossible.”

George B. McClellan

“Let me tell you that if your government had supported General McClellan in the field as it should have done, your war would have been ended two years sooner than it was.”

General Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of Staff of the Prussian Army and one of the leading military experts of the 19th Century

The Peninsula Campaign began with McClellan’s strategic plan for an amphibious operation. Leveraging the North’s naval superiority to transport and supply his army, he ultimately aimed for Richmond. Mac anticipated having over 150,000 men for the campaign as he set out for the Peninsula. However, once he landed, Lincoln would significantly reduce his army with the other troops spread around the Valley, D.C., and the Manassas region.

Mac had wanted more men for the offensive, but Lincoln wanted him to hold men back to guard D.C. Lincoln forced Mac to leave McDowell’s I Corps in D.C. along with the garrison already available. Lincoln now had a garrison of around 20,000 in D.C. and up to 74,000 as far as N.Y. that could be shipped/railed/marched to D.C. if it were attacked. Plus, McClellan had set up world-class fortifications. McClellan, McDowell, Winfield Scott, and every corps commander believed this was more than enough men to guard D.C. and supported McClellan’s plan to bring more men, but Lincoln would not allow it for fear of D.C. being attacked. Perhaps out of fear of Stonewall Jackson, it was Lincoln, not the general, who, in this instance, was being overly cautious. In Life and Campaigns of George B. McClellan (1864), author George Stillman Hillard wrote, “From the moment the Army of the Potomac landed upon the Peninsula an uneasy sense of insecurity took possession of the minds of the President, the Cabinet, and the members of Congress.”

So, Mac landed the army, which was slow-moving because it was massive and carried heavy siege equipment. He faced the largest army the South would field during the war, 88,000 (Grant faced 65,000 in ’64, with a more significant force under him than Mac enjoyed). Once his army landed, he was notified that Stanton had closed all the recruiting depots in the Union. His army would now have to do without either replacements or reinforcements during a major campaign.

This was a massive shock to Mac and the generals in the army. He then was told that McDowell’s 40,000 men near Manassas could not be used but must help defend against any possible action towards D.C., despite the fact that Confederates showed no signs of attacking and even burned the bridges south of Manassas as they retreated to defend Richmond. McDowell told McClellan this decision (McDowell protested it) was “Intended [as] a blow to you.” Then, McClellan was told the garrison of 10,000 men at Fort Monroe would also be withheld. Even critics of McClellan, like General Heintzelman, said it was a “great outrage” to withhold his army from his command. General Wells said it was the Radical Republicans trying to get Mac to resign. Harper’s Weekly stated, “It is impossible to exaggerate the mischief which has been done by division of counsels and civilian interference with military movements.” Once more, Mac was aggressive, Lincoln and the politicians conservative.

“In General McClellan’s opinion, the way to defend Washington was to attack Richmond; and the greater the force thrown against the rebel capital, the greater the security of our own.”

George Stillman Hillard, Life and Campaigns of George B McClellan

Mac was now forced to revise his plans because of Lincoln’s caution. In the revised plan, McDowell would advance on Richmond from the north with his 40,000 men and better protect against an attack by Confederate General Joe Johnston if he went north to Washington. However, as Mac argued, the attack on Richmond would force the Confederate army to defend their capital rather than launch a desperate attack on D.C. This disagreement delayed the start of the campaign, with Lincoln getting his way.

“Notwithstanding all that has been said and written upon this subject, I have no hesitation in expressing the opinion, that had not the President and his advisors stood in such ungrounded fear for the safety of Washington, and had not withheld McDowell’s forces at a time when their absence was a most serious blow to the plans of General McClellan, the close of the year would have seen the Rebellion crushed, and the war ended.”

Allan Pinkerton, Chief of the Union Intelligence Service, 1861-1862

Yorktown

Mac moved up the Peninsula towards Richmond and was promised McDowell’s men if D.C was free of threat. His army’s first encounter was with Confederate General John Magruder and a small Confederate force at Yorktown. Magruder skillfully deceived Mac into believing his force was larger than it actually was. He accomplished this by repositioning the same troops in various locations, acting aggressively, continuously moving small units, using ammunition freely, and setting up dummy defensive positions. This convinced Mac that the Confederate force was more significant than it truly was, prompting him to settle in for a siege while he awaited the arrival of his heavy artillery. Mac was concerned that his inexperienced troops might fail in an assault during the first battle of the campaign, which could damage their morale. Mac eventually captured Yorktown and 80 heavy guns without losses, but the delay gave the Confederates time to organize troops to defend Richmond.

[1] The two battles at the same site were referred to as First and Second Manassas by the Confederacy, First and Second Bull Run by the Union. I will stick to Manassas throughout, except that where quotations from the Union side refer to Bull Run this will be left unchanged.

Jeb Smith is the author of four books, the most recent being Missing Monarchy: Correcting Misconceptions About The Middle Ages, Medieval Kingship, Democracy, And Liberty. Before that, he published The Road Goes Ever On and On: A New Perspective on J. R. R. Tolkien and Middle-earth and also authored Defending Dixie’s Land: What Every American Should Know About The South And The Civil War, written under the name Isaac C. Bishop. Smith has authored dozens of articles in various publications, including History is Now Magazine, The Postil Magazine, Medieval History, Medieval Magazine, and Fellowship & Fairydust and featured on various podcasts including The Lepanto Institute.

Love the von Moltke quote!

Interestingly, Lee also said, when asked, that he thought McClellan was the most capable of the Union commanders he faced.

Yes, indeed, a great quote. I use it in part 2!

Pinkerton was one reason for McClellan’s cautiousness. He consistently overestimated the numbers of Confederates facing the Union Army. Sometimes greatly. For his part Pinkerton was probably thinking that should he underestimate them, and the North lose the battle, he’d be held accountable.

I’ve long believed that McClellan simply did not view the subjecation of the South as a desirable end to the war or for the future of the country or countries. He may well have believed the war should never have been prosecuted. In my old age I agree. In their old age, Henry Adams and both his Union gerenal uncles and the ambassador the the UK believed all were worse off for the war. Nothing good had been accomplished, and Leviathan had been unleashed from the chains of Republic.

Bought a full size brand new Confederate Flag today !

Proud to represent Dixie hanging it in my Office!

Nice Article looking forward to more,

Thankyou Sir.

Thank you! If I had known, I would have sold you mine. I have a collection of a half dozen or so flags I am looking to unload to someone who will fly them.

“Retreat’n” Joe Johnston, who could never hold a line. would have scuttled out of Richmond and rather promptly lost the war before he actually did. The serendipitous wounding of Old Joe and replacement with Lee gave the CSA a fighting chance. Davis and his favorite incompetent’s, Bragg and Joe Johnston costs the CSA its existence. McClellan was probably not as malicious as Sherman, Grant and Lincoln, he could have defeated Bragg and Johnston rather easily, but knew to be wary of Gen Lee !

And he also stated Jackson terrified him!

I guess Lincoln needed a general with a lot more blood lust. This article continues to reinforce my theory that he/his handlers wanted to shed as much Southern blood as possible. The carnage of Grant and Sherman were exactly what he wanted.

Lincoln absolutely saw victory from bloodletting and a war of attrition. He considered the war as a matter of mathematics.

Lincoln calculated following the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, 1862, that if the same battle was fought every day for a week, the Army of Northern Virginia would be wiped out, while the Army of the Potomac’s casualties could be covered from a reserve of other Federal armies, draftees and immigrants.