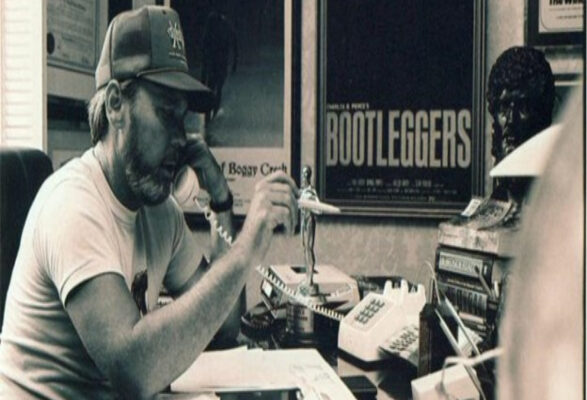

Filmmaker Charles B. Pierce was a man of many talents. During a career that saw its greatest amount of success in the 1970s, he worked in a wide variety of genres, though he was especially drawn to horror, crime, and Westerns. It was in the action genre where he would make his greatest pop cultural impact when working as a story writer on the fourth Dirty Harry movie Sudden Impact. It was Pierce who wrote the iconic line, “Go ahead, make my day” uttered by Clint Eastwood. According to Pierce, the line actually originated with his own father. Pierce, as a teenager of the 1950s, deeply admired the rebellious teen icons of the era like James Dean. His father, though, would have none of this and used that famous line to warn his son of the consequences of not mowing the lawn. But his career is much more than that, as will be examined in this series of articles. This first article will examine his life and general career, as well as the overarching themes present in his work. The second article will examine his most famous film, The Legend of Boggy Creek. The third article will look at his best work, The Town that Dreaded Sundown. The fourth and final article will examine Pierce’s work within the context of the now largely and sadly forgotten regional exploitation filmmakers of the 1960s-1980s.

Though technically born in Indiana, he would move with his family to the small south Arkansas town of Hampton when he was just a few months old, and it was here where he would always call home. His love of this region – north Louisiana/south Arkansas is one of the most notable elements in his body of work. He loves the region – its land, its history, and its people. To him, these are great people with fascinating stories, stories that needed to be told and he was the man to do it. What is even more telling his how much respect he has for his subjects. Unlike many “Hicksploitation” directors, Pierce has a lack of critical Southern stereotypes in his films. For as much as Hollywood has enjoyed trafficking in certain anti-Southern stereotypes, such as hackneyed stupidity, Pierce avoids this tired trope. There are stupid characters for comic relief, but these are the exception. Pierce also stocks his films with intelligent and seriously minded Southerners.

Martin Scorsese has long been noted as the director of ethnic Catholic America, especially Italian-Americans in films such as Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Mean Streets, and Goodfellas. Scorsese loves his people, and he is moved by the Little Italy that molded him. I would compare Pierces use of Dixie, especially Arkansas, to how Scorsese used Little Italy. Both men wanted to tell the stories of the guys they grew up with. But perhaps his daughter said it best, “Arkansas claims him, and he claimed Arkansas.” And he was an Arkansan through and through. He loved his state and her people. He loved the Razorbacks. And though he would often incorporate the neighboring regions of Louisiana and Texas into his work, it is clear that Arkansas holds a special place in his heart.

Pierce’s love of Arkansas is further evident in how long he remained a regional filmmaker. He would stay in his little corner of Dixie for almost all of his career, moving to California only in the mid-1980s when changing market trends killed off the independent theaters that played films by quirky oddballs like him. This is important, because upon watching Pierce’s better films, something that becomes apparent is that he had strong technical skills. His films are lovingly and beautifully shot and watching them now fully restored on Blu-ray further illustrates his technical talents. In other words, he could have easily moved to California earlier on in his career and found work easily, perhaps as a solid journeyman filmmaker, the kind of guy who made enjoyable, if not groundbreaking movies at a steady pace. But Pierce opted to stay in Arkansas where he could tell the stories he wanted about the people he thought mainstream Hollywood cinema was either ignoring or slandering.

Pierce made his last widely seen film in 1985 (Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues) and his last film in 1998 (Chasing the Wind). Although he moved to California in an attempt to continue his career, his move would not pan out, even as he penned one of Harry Callahan’s most famous lines. As talented as he was, he was just not cut out for the low budget cinema of the 1980s. The 1970s were far kinder to him. Despite his late career move, he would die in his beloved South, passing away of natural causes in Tennessee in 2010. He is missed. He was one of the best filmmakers of his ilk of the 1970s, and his films are just begging to be rediscovered. Two of those films will be examined in the next articles of this series.

Excellent article on the unappreciated genius of the 70’s. I fondly remember sitting on the tailgate at the drive-in watching Bootleggers. Another Pierce classic. Watch Boogy Creek at least once a year when the family carries the camper on the road 🙂

Arkansas is a wonderful state to learn living off the grid, it allows it easier than States that have laws making it Difficult.

Something to think about Dixie with the resent power outages!

Folks in mountain areas watch those near by streams with flash flooding.

Stay safe Dixie!

Bootleggers was my favorite.