One of my favorite pastimes for several years running has been doing serious genealogical work up and down my family (surname) lines. It might be the most important work I’ve ever done, in point of fact. I’ve literally written scores (perhaps even hundreds) of articles for my children and a select group of our broader family concerning the subject that you will never see published at our little oasis here at Identity Dixie, simply because my work in these veins is mostly private, family stuff. But there is stuff I’ve learned in the process that I am perfectly willing – and indeed, eager – to share with the broader ID readership and beyond. One of which is spelled out in the title of this article.

I first learned of this about eight months ago, or thereabouts, while deep in the process of trying to nail down my 2nd great-grandfather up the Stewart line to his family of origin. One of our sons – our eldest – has indicated to me that he thinks I should take the test necessary to become a professional or accredited genealogist. He says my work on the Morris side of things alone is, in and of itself, sufficient work enough to secure the sought-after status. He also thinks doing so will lend credibility to my work that some would consider lacking without it. He might be right, but I don’t know; and my genealogical work, as our son well knows, is certainly not limited to the Morris side of things in any case. Whether or not I have earned the qualifications to become an accredited “professional genealogist” is of little to no importance or consequence to this article or its subject matter in any event.

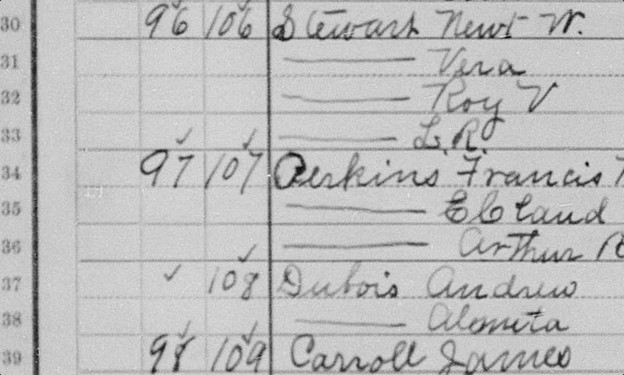

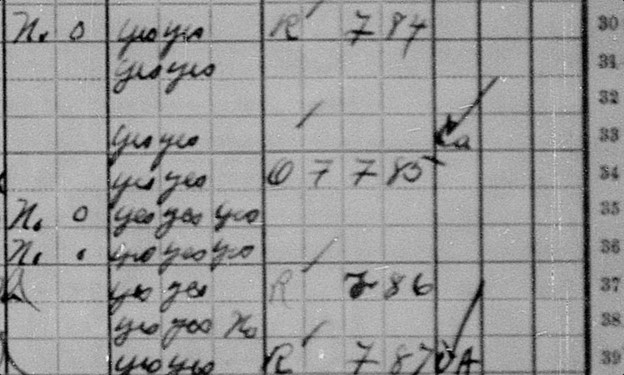

There is something unique about the 1910 Federal Census of which most of you are almost certainly unaware. Namely, that it contains a column that doesn’t appear on any Federal Census before (1900 or earlier), nor after (1920 or later) it. The column in question is numbered 30 on the list of 32 on that document, and its purpose was to document whether or not the person in question was “a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy.” For those who were yet living in 1910 to whom the column in question applied, the entry made on his line by the census taker was a simple “Ca” (Confederate Army) or “Ua” (Union Army) with an “n” substituted in the case(s) of Confederate or Union Navy men. Here are a couple of screenshots of a page from the 1910 Federal Census for Scott Township, Mississippi County, Arkansas, that is particularly relevant in my family’s case since it contains the entries for my 2nd great-grandfather, William Newton “Newt” Stewart, and his uncle living in his household at that time, L.R. Stewart:

As you can readily see from the latter of those screenshots, uncle L.R. (Uncle Larkin) was a veteran of the “Civil War” and a Confederate. He is said to be 60 years-old on that document, but I have it on good authority (the 1850 census, etc.) that Uncle L.R. was actually 62 years-old in 1910. In any case, I’ve personally utilized the information I’ve shared with you above to document that e.g., my little hometown in Southern Oklahoma had upwards of fifteen (15) elderly Confederates living there in 1910, and zero (0) Union soldiers or sailors. For some people, even some of my own blood relatives, this information is shocking to learn. It is sad, but they literally have no idea about who they are or where they come from. Indeed, this past Memorial weekend, I was visiting the graves of several of my forbears in our old cemetery. While there, one of my relatives showed up as well, and he and I got into a conversation about the Confederate flags someone had before placed on about two dozen of the graves. My cousin pointed out that “there is only one Confederate in this cemetery.” Which is true. But as I answered in reply, “yeah, but there are a bunch of sons and daughters of Confederates buried here, including our Morris and Newby ancestors.” My cousin didn’t argue with me on the point, but I could tell this was information no one had ever bothered to tell him before if anyone knew it.

One thing to keep in mind about the 1910 Federal Census and the column in question is that not all census-takers from every precinct of every county bothered to make the correct entries for the individuals to whom that column applied. One case in point among several I personally know of is precinct 5 in Ellis County, Texas, which, in 1910, was inhabited overwhelmingly by Confederates and/or their children and grandchildren, but not a single entry indicating so is made throughout the document in that column. I don’t know what the explanation is for the omissions in that column in Ellis County or elsewhere, nor do I care to speculate about it. There are other ways of documenting your ancestors’ service to the Confederacy than the 1910 Federal Census, but the point is in any case that the census in question is one of numerous ways of doing so that you were probably unaware of prior to reading this little article, which is precisely why I took the time to write it. I’ll write more about the “tricks of the trade,” genealogically speaking, in future articles.

God bless Southerners, and God bless the Southland!

Mr. Morris,

This post reminds me of the poem by Allen Tate, “Ode To The Confederate Dead”.

People who once lived are now forgotten. Glad to know you you are keeping their memory alive. Have a good day.

Thank you, dogface. Your comment reminded me of an old article I wrote for my children and larger family group several years back titled, Gone But Not Forgotten. As you know, that is an inscription often seen on old gravestones marking the graves of our forbears. Not just our Confederate dead, but also their children. As I wrote in the article, ‘I believe this inscription held true … for a time, before it became untrue … for a time. That latter time is over, for we are in the process of resurrecting the blessed memories of our dead, and of correcting the wrong done their memories during that “forgetful” time.’

Thank you for the comment, sir.