Until the 19th Century, vampires were barely more than zombies. In fact, early depictions of vampires were essentially that which we know of as zombies today: eternally hungry, undead who consume human flesh (brains being a more recent addition to some of the story telling), while disintegrating and smelling like the rotten corpses they are. However, the physically attractive, often sexually alluring vampire, is a relatively recent phenomenon in the story of vampires. That transformation begins with Dracula, written by Abraham “Bram” Stoker, an Anglo-Irishman, in 1897. For reasons that are cultural, political, and simply fun to explore in the month of October, this piece will focus on Stoker’s creation of Dracula, the modern depiction of vampires, and his overtly Nationalistic messages within the book.

To begin, vampires have been around for millennia. Explorations of the undead or the physical resurrection of supernatural creatures is first truly recorded in the various mythology of Ancient Greece. Dionysus is an interesting character in the vampiric story telling arch. The Ancient Greeks first record the product of a half-man, half-god who is torn asunder and reborn as early as 1300 BC. Certain myths depict Dionysus as originating from the East, and we get the first real glimpse of Dionysus in Euripides’ “The Bacchae,” (worshipers of Dionysus; written 405 BC). Euripides describes the female-dominated cult as one in which wine and sexual depravity surrounded the worship of a mystical and secretive cult at night. The followers engaged in sexual orgies, until they worked themselves into a frenzy by which Dionysus, the resurrecting half-man, half-god, returned to them and consummated their faith through additional intercourse. A key component of Dionysian worship was drinking both wine and blood.

Dionysian worship died with the ascendancy of Christianity in Greece. It is an interesting side note that many Biblical scholars miss, the first miracle of Jesus Christ, turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1-11), Jesus is crushing the Dionysian cult. Dionysus was the god of wine. Jesus, having been raised near the Decapolis (ten Greek city-states in Ancient Israel comprised of the descendants of Alexander’s soldiers), would not only be aware of the impact of Dionysus due to His omniscience, but the human Jesus would have been very aware of the importance of Dionysus to women in the region. More importantly, Mary, a woman of the region, would be well aware of the encroaching Greek influences on female Israelite society. In essence, by asking Jesus to perform this first miracle, she is saying to Jesus, “Show these women that they are following a false god; you, the Christ, have dominion.” Consequently, it is not a coincidence that among Christ’s first followers are the Greek communities that initially heard the Word through intermediaries, and eventually would enjoy the Evangelism and Epistles of Paul. Along with this conversion, the resurrecting god of sexual debauchery, wine, and blood sacrifices, would eventually disappear – until Ireland in the 9th Century.

During the latter part of the first Millennia, Norsemen were beginning to wreak havoc on Continental Europe, beginning toward the end of the 8th Century. After the demise of Charlemagne and the dissection of the Frankish kingdoms, Vikings began a very aggressive period of raids that ultimately became settled territorial conquests. Unfortunately, part of the destruction of various monasteries resulted in the destruction of remaining ancient texts. As entire cities were either conquered or established in England, France (Normandy), and Ireland (e.g., Dublin, Cork, and Limerick), a few holdouts emerged in areas that were deemed either not important strategically, difficult to access, or simply useless. Those areas were largely found amongst the myriad of Irish monasteries, that continued to translate Ancient Greek and Roman texts. Euripides “The Bacchae” was among those works preserved by Irish monks. The story of an attractive, undying half-man, half-god at the center of a blood and wine cult first found its way into Ireland at some point prior to the end of the 1st Millennia.

At nearly the same time, at the dawn of the 2nd Millennia, the Crusades introduced Western Europeans to Eastern European and Asian traditions, cultures, and superstitions. For centuries, stories throughout the Black Sea region and the Carpathian Mountains mixed tales of that which we would call zombies and the abject cruelty of Eastern European/Asian warfare. Whereas something as both overtly sexual and profound as Euripides would have had a limited audience of elites, fireside stories of the famished undead spread back to the West. Added to this mix was the introduction of Jewish folklore surrounding a legendary half-human, half-demon, named Lilith – a sexually provocative, who lurked in the night and consumes babies. The proximity of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe and especially near Christian communities in the Caucasus would have introduced some to tales of Lilith, only further contributing to vampire myths.

As the Eastern Theater of the Wars of Ottoman Conquest increased in brutality, various stories of barbaric cruelty began to carve out a depiction of Eastern European leaders in the minds of Western Europeans. Eventually, coinciding with the advent of the Gutenberg printing press, Germans and eventually other Europeans began reading stories of pitiless Black Sea Europeans and their ruthless Muslim foes. It is therefore not surprising that the story of Vlad the Impaler spread like wildfire after his death in 1477, as Western nobles viewed Romanians, Hungarians, and Balkan peers as savages.

Still, even after the notorious brutality of Wallachian (mostly modern Romania) ruler, Vladislav III, otherwise known as Vlad the Impaler, in the 15th Century, the mythology of vampires remained effectively zombies. Although surrounded by hyperbolic stories of blood worship and consumption, most of which was not true, Vlad Dracula (Vlad Son of the Dragon; Vlad II was Vlad Dracul – the Dragon) was never associated with vampirism until Bram Stoker. But a convergence of vampiric influences were floating in the West, it just needed someone to assemble them.

Bram Stoker was an interesting product of his times. He was a product of the Victorian age and carried much of the disciplined mannerisms of his era. As a member of a very small Anglo-Irish nobility (his father was a baron), Stoker would have been aware of his high-born status in an impoverished and politically changing Ireland. An Anglican and a monarchist, Bram Stoker embraced Home Rule for Ireland, albeit within the confines of the British Empire, making him a minority within a minority. Enjoying an elite 19th Century education in Protestant Trinity College of Dublin, Stoker seems to have embraced the Victorian philosophical position that men should have a diverse group of interests to be mastered, from mathematics to athletics to writing. He would have surely been introduced and required to have mastered the Ancient Classics and possibly Greek itself – which, at a minimum, would have introduced Stoker to Dionysus.

As a writer, Stoker seems to have written on a number of topics, from the duties of a civil servant to Irish folklore to romantic short stories. At some point, Bram Stoker was introduced to Hungarian diplomat and author, Ármin Vámbéry. Vámbéry, for his part, appears to have introduced the curious Stoker to stories of his native homeland as well as other stories from the region, including that of Vlad Dracula. As an educated member of the minor nobility, Stoker’s depictions of Eastern European warfare and military leadership would have no doubt added to his imagination as it pertained to Vámbéry’s descriptions and stories. Stoker would have been fed, as a boy, on stories of Slavic brutality and English dignity during the Crimean War. He would have surely known and read about the extraordinarily vicious massacre of the British Army in Afghanistan in 1842. Although the Afghans were not Slavs, nearly everything East of the Danube seemed disturbingly barbaric to polite British society of the Victorian Age. Yet, whereas Stoker would ultimately name his book, Dracula, and steal snippets of menacing Eastern European concepts on nobility, warfare, cruelty, and dreary darkness, the Dracula of Stoker’s book shares almost nothing in common with Vlad the Impaler.

Dracula is where Stoker’s personal isolation really shines within the original work itself. A fascinating story, many modern members of the LGBT cultural movement like to tie vampire stories to those of their own – effectively, forbidden love between those who are different from the rest. Exploring forbidden love is a theme in the book, Dracula, that many within that same community often comment as Stoker’s literary manifestation of his supposed repressed homosexuality. That is painfully myopic by a people with a lack of appreciation for historical context. The facts are more fascinating for those of us interested in Irish history and culture.

As a member of a very minor society of genetic elites – the Anglo-Irish Protestant nobility – Stoker was caught between two worlds. On the one hand, his family would have been far beneath Anglo-Saxon society of the time, and therefore, few women of higher born English society would be available to him. On the other hand, as an Anglo-Irish Protestant, he would neither have the opportunity to marry an Irish-Catholic, even one who may have money, nor would he, by virtue of his own obligations to his family lineage. This would have excluded the vast majority of women in Ireland. Thus, love was genuinely constricted by blood – a constant theme of Stoker throughout the book.

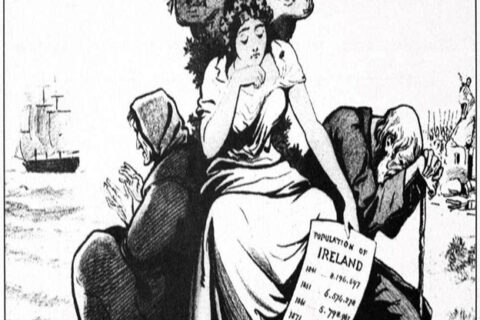

Stoker is not exploring a restricted sexuality in the Victorian Era. Stoker is exploring the importance and societal weight of genetic duty to one’s people. In this framework, the remarkable book uses components of Anglo-Irish perspectives on the Gaelic people who surrounded them. His depictions on low caste society and sexual immorality are fascinatingly interwoven in the tale. At the time, Irish women, most of whom married young and bred frequently, stood in stark contrast to higher born Anglo ladies, who typically married after some introduction of college, a male’s ability to prove his financial potential, and after prolonged courtship, had few children. To put this in perspective, Bram Stoker’s wife, Florence Balcombe, also from Anglo-Irish Protestant stock, married Stoker at the age of twenty and had only one child with Bram. By contrast, my great-grandmother in Cork from the same era married at the age of thirteen and ultimately had sixteen children. The real reason for impoverished Irish having as many children as they had at the time is a confluence of several factors, including duties to expand the family, the Catholic Church, and the preservation of both land (workers) and family (more children meant greater stability in retirement). Still, in typical Victorian Anglo-Irish fashion, the perspective of the Gaelic-Irish was that of a lascivious lot with little impulse control.

The totality of Bram Stoker’s creation is fascinating because it breaks the mold. He elevates the vampire from zombie to tragic beast – burdened with a blood lust that he can never quench until he is killed. Stoker does this while simultaneously providing a snapshot in time of the era and society from within which he resided.

Stoker takes Eastern European concepts on nobility – in this case, the warrior who needs to be brutal to beat back the more brutal Turks – and blends them with the sexually provocative, handsome and immortal Dionysus. He adds to the mix stories that traveled the centuries as to how vampires are killed (wooden stake to the heart) and their aversion to Christian items (no doubt, an elements of anti-Jewish perspectives wildly found in Europe at the time). He adds powers to Count Dracula that are relayed in early Irish folklore, such as the ability to summon animals and hypnotic spells. In short, Bram Stoker creates the noble, attractive vampire with immense powers who is both foreign and sexually uncontrollable. Prior to him, they were merely the walking dead.

Finally, Bram Stoker explores a Nationalistic impulse that is very obvious to any Nationalist who reads Dracula. Eastern traditions and cultures were beginning to penetrate English society, as the British Empire became more engrossed in Asian affairs and territorial conquest. None of this would have escaped the high-born Stoker. The mixing of blood between inferior people and Anglo elites was highly concerning. It would have been bad enough for someone like Stoker to have married a higher born Anglo-Saxon, but at least he was White. Eastern Europeans, Slavs, and Asians – cheap, imported labor – lurked the streets of Victorian London. The threat of these genetic inferiors descending upon White women – especially high-born White women – was a genuine fear of 19th Century gentlemen. However, more worrisome would have been the seemingly noble man of wealthy means defiling a White woman with his inferior blood through the use of hypnotic gestures, while enticing her naturally rebellious spirit. In this regard, it is impossible to ignore the fact that the physical depiction of Stoker’s Dracula matches very closely to higher-born Jews. The concern for Stoker in the 1890s was not likely solely Jews, but anyone from the barbaric geographic confines of the East. Still, Jews were quickly emerging in London’s socioeconomic circles at the time and much of Stoker’s work seems familiar with regard to his warnings on blood purity.

Victorian women were to be protected – from others and themselves – to ensure the integrity of race, privilege, and honor. It is therefore not surprising that the story really centers on the desire of a foreign-born, genetically inferior, minor noble with evil traits tied to his genetic construct to steal a high-born Anglo-Saxon woman. Dracula is anti-Christian thanks to his demonic curse. He is stopped by her fellow high-born Anglo-Saxon lover, who was able to thwart the desires of someone beneath them – despite all of Dracula’s power. It is, in my opinion, one of the greatest Nationalist and Gothic novels of all time – often one in the same when you read them closely.

The son of a recent Irish immigrant and another with roots to Virginia since 1670. I love both my Irish and Southern Nations with a passion. Florida will always be my country. Dissident support here: Padraig Martin is Dixie on the Rocks (buymeacoffee.com)

Very interesting read–not sure if I completely agree, but I think you have valid points for consideration.