Work—work—work!

The Song of the Shirt, by Thomas Hood

My Labour never flags;

And what are its wages? A bed of straw,

A crust of bread—and rags.

That shatter’d roof—and this naked floor—

A table—a broken chair—

And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank

For sometimes falling there!

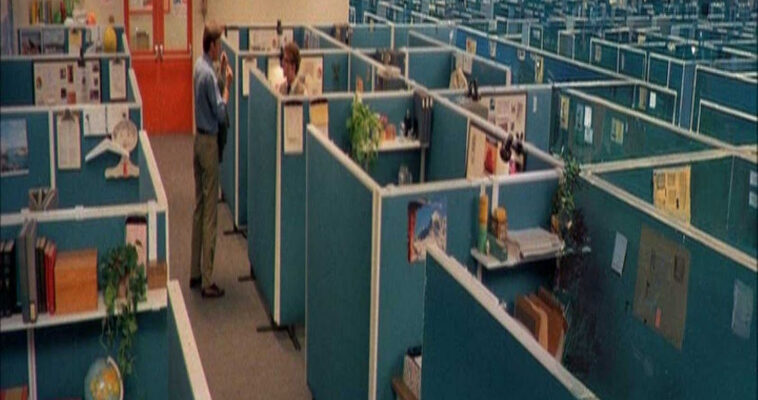

As you well know, the term “wage slave” and its derivatives is bandied about quite a lot in the modern world, and rightly so. Any term and the phenomena it describes are, of course, closely connected. It isn’t therefore surprising when we find a given term’s earliest known usage fixing a name to a set of conditions we’re all more or less familiar with in our own day and age. Sometimes, however, when we trace these things back (and/or, when someone else is kind enough to do our work for us), we’re also treated to the unexpected benefit of tasting the bitter-sweetness of poetic justice, in addition to gaining new and useful knowledge and insights.

Such a thing as I have described above happened to me a few years back, when I used the term in question in a comment at the traditionalist website, The Orthosphere. Now, had you the benefit of having conversed with Orthospherean contributor, Prof. Smith, as much as I have the last several years, you would enjoy the benefit of knowing, with me, that he is a veritable ‘wealth of knowledge’ when it comes to the origin of terms in our common lingo; terms that the great majority of us simply take for granted, never taking time to search out their origins, if we’re curious about their origins in any case. Sometimes I am (curious about their origins), other times not s’much. But, even when my curiosity is piqued as to a term’s origin, or probable origin as it were, it is nevertheless often the case my curiosity, in and of itself, is not enough to compel me to do the necessary work to find it out. That is a personal defect, likely attributable to at least a little “intellectual laziness” on my part. But you’ll pardon me for that, I trust; there are only so many hours in a day, and I am not a professional scholar or a college professor after all.

Notwithstanding all of the above, and to continue with my story, I answered the musings of another commenter to Prof. Smith’s article in question by writing, in part, that someone or other in history had good sense enough to see that the then much vaunted term “free labor” would be better and more accurately described as “wage-slavery.” Now, when I wrote that I had absolutely no idea who this person might have been, and only a (fairly strong, but nevertheless) suspicion of how far back in time one would need to go to find him. I did know, however, that the term didn’t just appear out of thin air, and that the American “Civil War” era was the likely place to begin looking for him. I also knew that if anyone in my circle of friends and acquaintances had any knowledge of the term’s origin, and/or of its originator, it would be Prof. Smith, which is part of the reason I crafted my statement the way I did. Yes, yes, I was sort of “baiting” my friend, Prof. Smith; but seeing as how this is kind of his “thing,” I didn’t think he would very much mind, nor that I was overstepping any bounds in doing so. In any case, here is Prof. Smith’s more than adequate, informative reply to my thinly-veiled query:

I found what may be the first use of the phrase wage-slave in a newspaper article by the English Chartist Ernest Jones. He used it to describe employment at subsistence wages, so that a worker could never accumulate capital with which to start his own business, or even purchase the leisure to seek a better job. If all my wages are required just to stay alive, and all my time and energy is absorbed in the effort to earn those wages, I am a true wage slave. Jones was a friend of Marx and Engels, and the idea of wage slavery is obviously related to the Marxist notion of immiseration. That doesn’t mean it is wrong, as anyone trapped in a crappy job knows

“I assert that capital, being possessed of a monopoly of political and social power, uses that power so, as always to ensure the supply of hireable labor remaining greater than the demand . . . by which to force wages down, and keep the wage-slave beneath the heel of capital.” Ernest Jones, Notes to the People (1851).

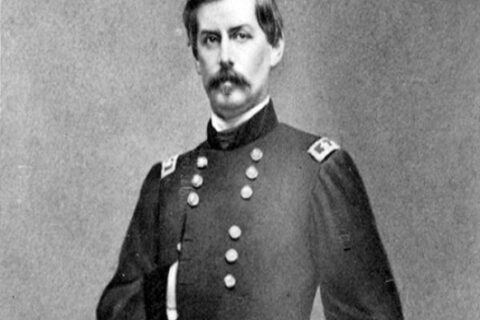

The first American usage that I found came a decade later. Here it was said that wage slavery existed when men could not exit the labor market and farm free land. The context was a speech advocating the distribution of Southern plantation lands to smallholders from the north. But the principle is the same. The more difficult it is for a man to quit his job, the closer he is to a wage slave.

“The maxim of the slaveholder that ‘capital should own labor,’ will be as frightfully exemplified under the system of wage slavery, the child of land monopoly, as under the system of chattel slavery . . .” George Washington Julian, Homesteads for Soldiers on the Lands of Rebels (1864).

Disciples of Mammon make much of the fact that workers’ wages rose, so that no one in the developed world is nowadays subsisting on true “starvation wages,” but “starvation wages” is not the essence of wage slavery. The essence of wage slavery is that all the exit doors are locked. As you say, the fixed cost of taxes make it hard to accumulate capital, as do the extravagant expectations of the American standard of living.

The bitter-sweet pill of poetic justice I alluded to in the opening paragraph of this article, is tucked away in the second of Prof. Smith’s findings. When you travel back in time and get a feel for the real conditions that the average “free laborer” worked under in the Yankee states in the decades immediately surrounding the so called Civil War era, you notice very quickly indeed that the class of laborers in the South the Yankees were hell-bent on “emancipating” and instantly turning into “freedmen” and “free laborers” were in for a massive, community-wide letdown once the new wore off their liberation and they suddenly came crashing into reality. They’re still pissed about it to this very day, but they’re too blind, stupid and incorrigible, to see who the real culprits were entirely responsible for their misery.

But the irony of it all is that these common (Yankee) thieves who stole the plantations from their rightful owners, with the promise that they would receive 40 acres of the finest Virginia soil and a mule or whatever for their efforts, were prohibited from taking advantage of their benevolent government’s kindness and its appreciation for their services by the inescapable conditions of the very system they fought to impose upon the South. That must have been a very bitter pill to have to swallow for the veteran Yankee foot-soldier, who expended so much of his own blood, sweat and toil, to rape, steal, pillage, murder and burn down the South and destroy her institutions the way he did.

And, indeed, he had already begun to grumble about this ungrateful state of things when he was yet one of the “Bummers” doing the bulk of the work stealing everything of value he could lay his hands on before he set his victims’ homes ablaze; he thought it very “unfair” that he was doing the lion’s share of the actual thieving and pillaging, only to have to share merely the fifth part of his loot with his fellow enlistees; the remaining four-fifths being confiscated from him and unequally divided among the officers of various ranks. It galled him to no end, as you can well imagine it should have, that while the officers dined on the silver setting and drank from the finest wine glasses he had taken with his own hands and carried five miles or more back to camp in his own knapsack, he and his fellow Bummers were relegated to haggling over who would get the fork, who the spoon, and who the butter-knife one of his comrades had stolen from the cottages of the hapless negro field hands. Of course, he could (and sometimes did) hide part of the best of what he had stolen fair and square, but he did so at his own risk, for if he were found out in this selfish, dishonest scheme his best buddy would not hesitate to “out” him with the higher-ups (in the interest of justice, of course), and his punishment was always severe and painful, if in fact he escaped with his life.

Now, you might think, or get the impression, that in the paragraphs immediately above, I am exaggerating for effect. And if that is in fact what you’re thinking, let me hereby assure you I am not. Indeed, this is a common theme in numerous (in virtually all, in point of fact) of the wartime journals I have read, Northern and Southern alike. Read, e.g., Virginia Lomax’s memoirs, or Mrs. Greenhow’s; read the several accountings of the daily goings-on within the walls of Andersonville prison, including John Ransom’s; read Georgia girl, Eliza Francis Anderson’s, “wartime journal,” or that of Emma LeConte, etc., etc., etc. I could go on naming titles and their authors, but you get the point.

Common sense – which was always, and remains to this day, more plentiful and broadly distributed in the South than it ever was in the Northern states – dictates that whenever so many first-hand witnesses, too far separated by chance and circumstance to conspire in ‘getting their stories straight,’ describe the same happenings in virtually every gory detail, then the details these individuals took pains to describe must therefore be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth so help them, God.

I don’t know why, but I derive a great deal of pleasure and personal satisfaction from knowing that the common thieves and criminals in the Yankee army spoken of above, found themselves in the ungrateful situation that would prevent their ever taking full advantage of their benevolent government’s sacred promises to them and its post-war generosity. It is also the height of irony that the term “wage-slavery” was first used in America to describe the injustice of the system under which common thieves and common criminals perpetually labored, without any hope of “upward mobility” or of living the old American Dream. Yankee style!

‘Murika! Land of the “free,” or home of the wage slave? You decide.

Wagery.

Yes, we hear a lot about slavery. But capital learned quickly that it costs a lot if money to house and feed entire families of negroes, including the very young and old who could not work (hey, the original social security in America), so they decided it is best to internalize all profits, and externalize all costs, through tried and true wage slavery, where the young, old, and feeble had to fend for themselves (or through relatives) or die. Much like today, where corporations internalize all profits and (try to) externalize all losses and negative effects of their activities in lowering costs and obtaining ever-cheaper labor (the open borders crowd, for example).