Virginia, The Old Dominion, the Capital of the Confederacy, the Birthplace of America, sits atop the imagery often considered when addressing the War Between the States. Founded as a faux-English paradise, Virginia housed many related dynasties of old blood English cavaliers seeking to recreate the English gentry within the gorgeous Virginia countryside, economically centering on tobacco and rice plantations. The focus of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns and the political capital of the Southern Government, Virginia sat in a moderate stance among its regional sister states during the 19th Century, yet developed into an increasingly conservative and stalwart segregationist state as the 20th Century unfolded. Its 20th Century conservatism stemmed from the tempestuous, corrupt Reconstruction Era which preceded it. Though not quite so riotous as the rest of its Dixian sister states, the inconclusive end to Reconstruction in Virginia left a populist undercurrent which would define politics and race relations well into the 20th Century. A landmark in socio-political affairs in America’s birthplace, this essay will examine the economic, political, and social affairs of Reconstruction in Virginia.

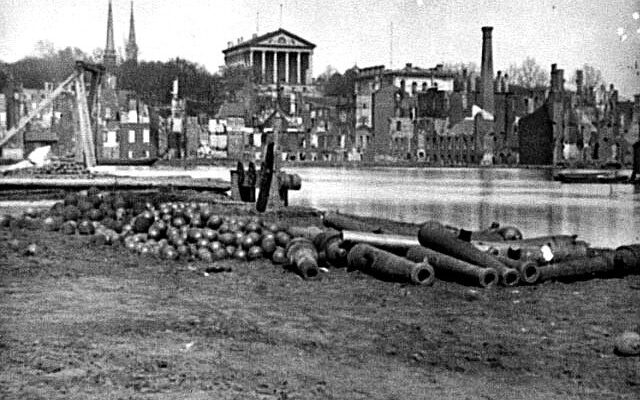

The economy of Virginia laid in absolute destitution. Richmond was left in ruin, and vast swathes of the state were abandoned or destroyed. Planters lived in poverty, farms were burned, and crops were scarce. Freedmen often resorted to lethargy, not being obligated to work or adhere to labor contracts. The eastern regions of Virginia would remain in poverty for generations afterward. Though eastern sections would find respite in their existing infrastructure, cities, and large population, western counties would continue in destitution for generations. Thankfully, the state would rebuild relatively quickly in the aftermath of the War. By the 1870s, tobacco had found a moderate resurgence, and many miles of railroad were built. Cigarette manufacturing would also experience a boom during the Gilded Age.

More or less an interlude in Virginia politics than an actual definitive period, the following era of Virginia politics was mired in corruption. Reconstruction’s political end left in its wake a weakened, factionalized Republican party which would later split, forming the brief but powerful, populist, anti-corruption Readjuster Party at the behest of William Mahone. Profoundly effecting the social circumstances of the Old Dominion, Reconstruction bred a strong populist current which would permeate within the locals who found themselves unsatisfied with the conclusion of the period’s political affairs, a feeling which would propel Harry Byrd Sr. to power a few generations later.

Presidential Reconstruction proceeded largely without incident. Francis Harrison Pierpont, the wartime Union Governor of Virginia elected by the Wheeling Convention in 1861, was quickly recognized by President Johnson after the War. It was in this instance Virginians stood a head above many other Southern states, save possibly Tennessee. The wartime Alexandria Government of Pierpont simply assumed the responsibilities of government, circumventing anarchy and the need for an election. Reorganizing quickly, Virginia’s governor was moderate. Discouraging Radical sentiments, Pierpont created unpopularity among a strong faction of Republicans and did little to gain allies within the competing Conservative Party. Pierpont became so unpopular over time that he would eventually be removed by General Schofield, the commander of Military District One, and replaced with Henry Wells.

Henry Wells’ tenure largely lacked notability. His brief stint as Governor mostly involved the vote on the new “Underwood Constitution,” as it was called, as well as some debates on it. Radical Provisions were supplied to the Constitution, but separate votes were held on them. Wells would step down early from the governorship in September 1869 following his electoral defeat in March 1869 with Gilbert Walker appointed provisional governor in his place until being properly inaugurated in January 1870. Walker, the moderate Republican, ran against Wells, an ally of the Radicals, in the 1869 election.

The political incidents of 1869 would form the downfall of Radical Reconstruction in Virginia. During the previously aforementioned election, the Underwood Constitution was ratified with the Radical provisions being wholly rejected. Though the Radicals would continue to comprise a faction of the Virginia Republican Party, their power was significantly weakened from thenceforth, largely due to their distasteful antics during the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868, as well as, the small Negro population of the state in proportion to the White population.

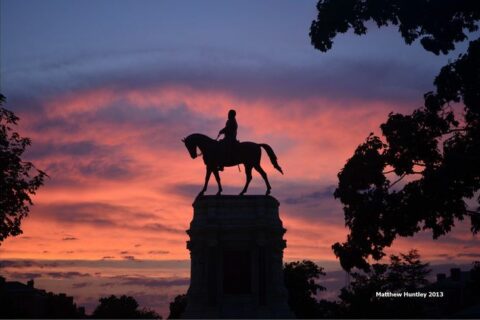

Walker’s success during the gubernatorial election would also further crush Radical aspirations. A moderate Republican, he worked across the aisle with the Conservative Party and would eventually join said party. Walker’s election was not much of a revolution or a struggle for “Redemption,” but instead a result of a crafty backroom deal. William Mahone, one of the most superlative and skilled Virginia statesmen of the late 19th Century, convinced the Conservatives to back a moderate Republican against the Radicals. This bid worked, and the Radicals would never again reach their pre-1870 power. In effect, Virginia had been “Redeemed,” the only Southern state to do so peacefully and the only one not to have elected a Radical government in a civilian election. However, the Republican Party would still play a major role in Virginia politics until the 1880’s. As the party declined, William Mahone would lead a short-lived but powerful populist faction, the Readjuster Party, which would splinter away from both the Republicans and Conservatives. The Readjusters’ idealism would not last. Determined to win, the Conservatives intensely organized down to the local level, and the party rejoined with the Democrats in 1883. From thence, Democrats would control Virginia for generations. Writing and ratifying a new constitution in 1902, these Democrats would solidify the era of Jim Crow in Virginia and cast away the shackles of Republican influence for many years.

Aside from the brief political Reconstruction of the state, the social factors the population lived under were astutely downtrodden and solemn. Though Virginia holds a reputation for lack of solidarity with its Southern sister states, it more than made up for this in the War. Alongside Tennessee and North Carolina, Virginia endured much of the fighting and populace contribution. The Union Army left no stone unturned, and Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley limped on in a condition of astute, ruinous desolation, the former making a quick comeback while the latter would suffer for generations afterward.

Virginia remarkably proceeded as the only Southern State to peacefully overthrow the Radical regime. This had primarily to do with the lack of paramilitary encroachment into the state as well as a rapid fracturing of the Republican Party upon its ascertainment of power in 1867. Virginia cast the shackles of Radicalism off of itself in 1869, only a mere few months after the first signs of Ku Klux activity emerged within the state. Little else may be said. Virginia carried a history of moderate stances, and the whole brunt of Union invasion did not turn it from this caricature. However, this moderation would not last, and Virginia would rise as a prolific pro-segregation state following its ratification of the Constitution of 1902, its sterilization and blood purity laws, the rise of Harry Byrd, and its adoption of “massive resistance.” Contrarily, it still avoided violent confrontation during even the 20th Century. Virginians stood as the only Southerners to “Redeem” themselves through politics alone.

The story of Virginia’s “Redemption” is a curiously peaceful one. Its economic, political, and social Reconstruction occurred quickly and generally without incident. The populist undertones of the “Redemption” of Virginia would leave the state without a Democratic Party and with a still intact Republican Party. Redemption’s inconclusiveness in the Old Dominion would be followed by a change of hand and strong bipartisan feuding which continued to neglect Virginia’s western sections, setting the stage for the ascendance of Jim Crow laws, segregation, and the Byrd Organization of the 20th Century.

“The White people of the South are the greatest minority in this nation. They deserve consideration and understanding instead of the persecution of twisted propaganda.” –Strom Thurmond