When I got out of the Air Force and returned to Oklahoma, I went straight to work in construction for a middle-aged contractor named Paul Ellenberg. Ol’ Paul was kind of “high strung,” and me and him didn’t always quite see eye-to-eye, due in part to that aspect of his nature vs. mine.

Notwithstanding our differences on this and that, I will always be indebted to Paul for his willingness to instruct me where I needed the most instruction. As he explained to me one day about a month after I went to work for him, “your work is excellent, Terry, no one can dispute that; your problem is, however, that you’ve never put together a good system.”

While I can’t say I received that bit of constructive criticism all that well to start with, I can honestly say that, given a little time to think on it, I humbled myself and came to realize Paul was right, and immediately thereafter set about to correct that personal defect. Which of course resulted in my saving myself lots of time and unnecessary headaches, down the road.

Perhaps you’ve seen the YouTube video featuring a number of new Harvard graduates attempting to explain why we experience four distinct seasons in the temperate zones, on this mortal coil of ours. I use the phrase “attempting to explain,” because, well, “noble effort” and all that notwithstanding, these particular graduates don’t know their hind parts from a hole in their heads when it comes to the question at hand. You should give the video a look in any case. It is an old video, but I have no doubt the problem persists to this day, and likely to a greater degree than it did when that video was made.

If the narrator is right in her assessment – that the problem of carrying childhood misconceptions into and out of college level courses stubbornly persists in spite of the fact that the very principles in question are taught throughout the grades – then obviously we have a big and pervasive problem successfully conveying this simple knowledge throughout the various education levels. The question then becomes, what is the source of that defect, that it might be corrected? Or, with respect to young homeschoolers in particular, that it might be avoided altogether.

My educated guess is that the source of the problem is likely one of two things, or possibly a combination of them both: either (1), the teachers don’t know the subject matter well; and/or, (2), they don’t know how to teach it effectively if they do in fact know the subject matter well. Inasmuch as the latter is a source of the problem, they (teachers) have probably never put together a very good system for teaching these principles. At the risk of coming across as a “know it all,” I’ll tell you straight up that no child of mine, above the age of ten years-old, was ever as ignorant on this particular subject, as the Harvard grads in that video. Nor will they ever be. I would be a bungling educator indeed, if they were.

Bear in mind as well that there are three minimal requirements for intelligent communication between minds – (1), a mind capable of transmitting an intelligent thought, (2), a mind capable of receiving an intelligent thought, and, (3), a language, or some other means of communication, common to them both. I’ll take the narrator’s word for it when she says the principles in question are taught throughout the various education levels, and simply point out, as I’ve pointed out many times before, that it is usually #3 wherein we run into a problem. In other words, and with respect to this particular topic among others, at least part of the problem here is that something is apparently getting “lost in translation,” in a manner of speaking.

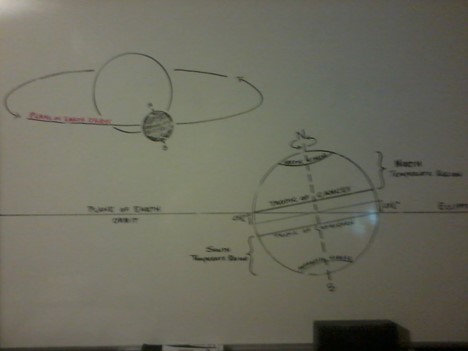

When I teach this subject matter to my kids, I do so by way of two overlapping but distinctive methods. (1) illustration, and, (2), by way of demonstration. When I say “illustration,” I mean, illustration in its literal sense – I mean that I draw or sketch this process out on a dry-erase board for the kids to take a good long gander at, as in the following illustration:

Now, I have a bunch of kids, so I’ve done this many times in the past. As such, I can draw all of that out in about ten minutes time, blindfolded, and with half of my brain tied behind my back, if needs be. I’m certainly aware it isn’t that easy to start with, but practice makes perfect and all that, as they say. By “demonstration,” what I mean is that I physically demonstrate to the kids how this process works throughout earth’s complete orbit. But how?

Okay, what you need for demonstration purposes is a globe of the earth, first off. Secondly, you need something or other that will serve as a good “sun.” The sun, as you know, is huge by comparison to the earth, but it doesn’t appear to be so from 93 million miles distance, and from our line of sight it is no bigger in diameter than the moon. So, get yourself a tennis ball, or, more preferably, a softball, and use that for your “sun.”

Seat your kids at the kitchen table, and set the “sun” at the table’s center, resting on something or other that will keep it in place – a pvc collar works well for this. Take the globe in hand, and begin walking around the table/sun, taking care that you keep the direction of earth’s tilt always in the same configuration as when you began. For example, if you begin with the top half of the globe leaning directly towards the south, keep it leaning towards the south throughout the entire walk-around, while maintaining the correct degree of angle. For, you see, this is precisely how the earth behaves in its orbit around the sun. And this is key to understanding how we get the seasons.

A convenient place to begin is at the point of your “orbit” that corresponds to Winter Solstice, since winter solstice is very near the beginning of the New Year. When I demonstrate this for the kids, I usually make several successive passes around the table. During the first pass, I make sure they understand the configuration of the earth on its axis in relation to the sun at the solstices, as well as at the places that correspond with the equinoxes. During the second pass, I begin at the month of January and count the months off as I’m making the pass – January, February, March, and so on. On the third pass, I have the kids name off the months as I make the round in silence. The fourth pass, and as many passes that should come thereafter, is dedicated to beginning at the place in our orbital demonstration at which the position of the earth in its circuit corresponds with the month of the child’s birth. Kids learn and retain these sorts of scientific principles very easily and much more readily when they can connect them to themselves and their place in the world.

Always keep in mind that the principles being taught in these sorts of lessons are not intuitive to the average person’s mind, regardless of age, or of how intelligent he or she happens to be otherwise. This is why it took so many centuries for mankind to figure out that the earth is not in fact the center of the universe, or of the solar system for that matter. It is also the reason why those Harvard graduates in that video could not correctly reason their way through the process by which the seasons occur.

This being the case, you’ll likely have to point out to them initially that, e.g., during the northern summer, the northern hemisphere is tilted towards the sun, resulting in more direct sunlight and longer days, hence resulting in the build up of heat on that portion of the planet. This is why I use a smaller (as opposed to a larger) sun for demonstration purposes; your kids will more readily see (through the “mind’s eye”) the contrast between direct and indirect sunlight as they imagine light from your “sun” striking the face of the globe, when the size of the sun corresponds with its size as we see it in reality from 93 million miles away. You can also demonstrate this by using a flash light under dimmed room lighting, if needs be. In any case, once you’ve set their minds on the correct path by way of this simple demonstration, your kids will reason their way through the rest of the process with no need for further instruction on your part. At that point, they couldn’t “unlearn” the elements of the lesson if they would.

There you have it in a nutshell. If you are a young parent, and/or a homeschooler/would-be homeschooler, I hope the methods I’ve shared in this article will be of use to you in the future. Take it from an ‘old hand’ at this, if you utilize the several methods more or less as I’ve described them above, your kids will pick up on and internalize the lesson quick, fast, and in a hurry. Once internalized, they’ll never forget it; if ever thereafter they find themselves on the receiving end of the question posed in that video I linked to above, they’ll be able to explain it in a lot fewer words than I’ve committed to this article, and probably in less time than it took you to read it. Oh, it might take them a few seconds to recall from memory, but at least they’ll have the memory from whence to recall it, unlike the college grads in that video. There won’t be any talk of highly eccentric orbits, I can assure you of that.