All warfare is based on deception. This age-old quote is known by just about anyone who has even a marginal interest in military history. However, Sun Tzu wrote these infamous words in the context of a literal battlefield. If you are near your enemy, you should make him believe you are far away. Make your enemy believe you are weak when you are strong and strong when you are weak.

But, this powerful quote had a different meaning in the War of Northern Aggression: all warfare is based on propaganda. From the earliest days of the War, and even before the War, Abraham Lincoln and the Northern Republicans had a special weapon in their corner. This weapon would be used to push some of the greatest propaganda tales of all time. This weapon was Horace Greeley.

Greeley was born in February of 1811 in a small town in New Hampshire and to a family of English/Scots-Irish descent. As he grew up, it was noted that Greeley had certain eccentricities that have led modern historians to believe he had Asperger’s. Greeley was also highly intelligent; in fact, the townspeople offered to pay his way through school which adds to the notion that he was likely autistic. Greeley’s unsuccessful father refused the charity offered by the townspeople, and ended up moving his family multiple times in order to escape debtors’ prison (it’s worth noting the irony of Horace’s father’s name, Zaccheus). By the time Horace was 11, the Greeley family had moved several times through the far north of the United States, never truly settling down.

Soon after Horace’s 11th birthday, he ran away to become a printer’s apprentice. Horace Greeley wandered town to town through New Hampshire and Vermont until he found a publisher willing to hire an 11 year-old boy. Nobody would. When Horace was 15, he finally received his first job as a printer’s apprentice and began working. By all accounts, Greeley was a hard worker and was well respected by the far-Northern Yankee communities he called home. Greeley was notorious for reading his way through entire libraries and being a sort of “walking encyclopedia.” Greeley, ultimately, converted to Universalism, which greatly impacted his political views. This is where things get interesting.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Greeley became a prominent editor in New York City, where he adamantly supported the Whig Party, opposed the annexation of Texas, and the institution of slavery. In the late 1840s, Greeley’s politics became increasingly liberal and progressive. Greeley stated in 1846, “I cannot see how the ‘Woman’s Rights’ theory is ever to be anything more than a logically defensible abstraction,” but only four years later, in 1850, he adamantly endorsed The First National Woman’s Rights Convention. By 1858, Greeley openly supported Lydia Ann Jenkins, one of the first female “ministers” in the U.S., and an aggressive feminist. Greeley would often “review” Jenkins’ pastoral messages in his papers, thus driving Jenkins to national fame and normalizing the concept of female pastors in the American mind.

Greeley’s liberalism did not stop at womens’ rights, however. In 1851, Horace Greeley not only pushed socialism in the United States, but outright hired Karl Marx. Through the year 1857, Karl Marx was published in the New York Tribune, one of the most read Northern newspapers, once a week. At one point, the entirety of Revolution and Counter-Revolution was in circulation in Yankee cities. Economic hardship resulted in Marx being laid-off for a few years, but he resumed writing for American newspapers in 1861 and continued through the War.

All the while, Greeley continued to publish things like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and horrible tales of Southern cruelty to slaves. The groveling populations of industrial Northern cities consumed these papers like starving animals feasting on carrion. Karl Marx and Harriet Beecher Stowe alike were read in the four penny papers sold on the streets of New York, and were subsequently discussed in taverns and bars. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “John Brown’s Body,” and the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels convinced thousands of young Yankees to march into the formidable meat-grinder that was the Confederate Army. The anti-drafters understood this and stormed Horace Greeley’s headquarters in New York City during the 1863 Draft Riots.

As the war went on, the Yankees were losing their will to march off to war against the South. Many anti-drafters made the argument that the southerners were simply protecting their homes and meant no ill will towards anyone, even blacks. This idea began to take hold in the Northern mind, thus reducing the will to fight, so Greeley devised a plan. Greeley would make every Union loss a massacre, and every Union victory a great triumph. Most notably, Greeley used the Battle of Fort Pillow to shift public opinion towards hate and fear of the South.

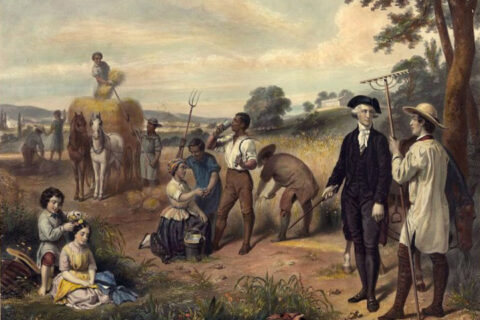

On April 12th, 1864, Confederate cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest had surrounded Fort Pillow, a former Confederate fort that had since been taken by Union forces and was occupied by a black artillery unit and a white cavalry unit. It is important to note that at this point in the war, the fort had little military significance and was actually inhabited, contrary to the orders of General Grant and General Sherman. Northern businessmen were actually using the fort as a forward operating base in a looting and pillaging operation in west Tennessee. Forrest decided to assault the fort due to the fact that every town he went to in the Memphis area had the same story: runaway slaves turned Union soldiers, led by Yankee cavalry men, raped and stole from unsuspecting townsfolk.

Forrest offered the inhabitants of the fort a chance to surrender, declaring: “If I storm your works, you may expect no quarter.” However, Union Colonel Stephen G. Hicks responded by saying Confederates can expect no quarter in return if they stormed the fort.

Forrest began a bombardment with his artillery and peppered the fort with sharpshooter fire for over four hours. A minor assault on the southern portion of the fort easily captured several barracks. Forrest then sent a letter requesting an unconditional surrender, that read, “The conduct of the officers and men garrisoning Fort Pillow has been such as to entitle them to being treated as prisoners of war. I demand the unconditional surrender of the entire garrison, promising that you shall be treated as prisoners of war. My men have just received a fresh supply of ammunition, and from their present position can easily assault and capture the fort. Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.”

This marks Forrest’s second offer of surrender. With all commanders in the fort shot dead by cannon fire or sharpshooters, the ranking officer, William F. Bradford, bravely penned a response to Forrest, stating simply, “I will not surrender.” And so the main assault began.

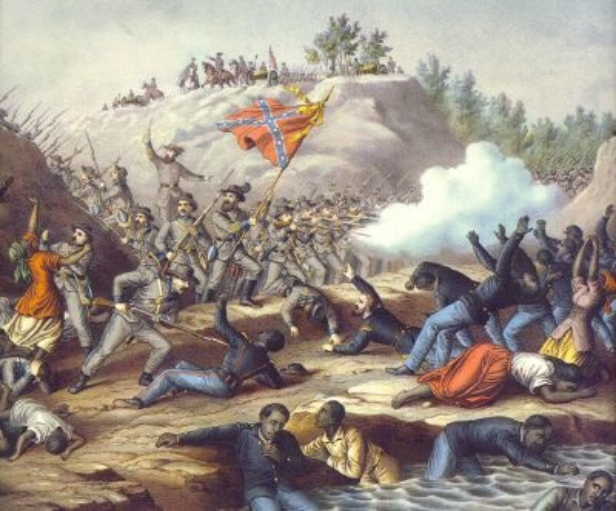

Forrest’s forces easily captured the fort, but met ferocious yet brief resistance once inside the fort. Both Northern and Southern accounts attest to the madness that ensued after Confederate forces took the walls. Some Yankees, including the garrison’s physician, claim that some black soldiers would feign surrender, then pick up a rifle and fire into the backs of Confederate attackers. Others claim that buildings in the fort would have a rifle out of one window, and a white flag out of another. This confusion is not unheard of on battlefields throughout the American Civil War, or any other military conflict throughout history. Many

famous defenses have had such stories arise, from the Battle of the Alamo to Iwo Jima.

However, by no account were women and children massacred in the ensuing battle. Horace Greeley leapt onto the easily-sensationalized story of enraged, white soldiers brutally murdering hundreds of innocent and surrendering black soldiers and their families. Harper’s Weekly reported that, “The annals of savage warfare nowhere record a more inhuman, fiendish butchery than this, perpetrated by the representatives of the “superior civilization” of the States in rebellion.”

The article continues to describe the “details” of the “massacre”: “Both white and black were bayoneted, shot, or sabred; even dead bodies were horribly mutilated, and children of seven and eight years, and several negro women killed in cold blood. Soldiers unable to speak from wounds were shot dead, and their bodies rolled down the banks into the river. The dead and wounded negroes were piled in heaps and burned, and several citizens, who had joined our forces for protection, were killed or wounded. Out of the garrison of six hundred only two hundred remained alive. Three hundred of those massacred were negroes; five were buried alive.”

Northern readers were appalled at the barbarism supposedly perpetrated by the Southerners at the battle. Throughout the rest of the war, “Remember Fort Pillow” became a rallying cry among Yankee soldiers, both black and white. Patches were made with the deceiving slogan and were worn by soldiers across the Western Theater. Hilariously, Northern soldiers captured at the Battle of Brices Cross Roads had large holes in the sleeves of their uniforms, as they had cut the patches off as Forrest closed in on them.

The weight of the Yankee narrative of Fort Pillow has been felt from the time of its publishing to this very day. At the time, the narrative caused the Union to no longer trade prisoners and it inspired increased hatred on the battlefield. Lasting images of the event depict white men clad in grey ruthlessly bayonetting unarmed black soldiers and wounded black women and children crawling and screaming as they’re butchered by the ruthless Confederates. You can be sure to hear of the “horrible atrocities” at some point in “Black History Month.”

Who wouldn’t be appalled at such a sight? Any sane person would agree that it is immoral to bayonet women and children, regardless of race. No one argues for the morality of burying innocent men alive. No one attempts to justify the fantastical war crimes committed by the Confederates in Greeley’s false narrative of the Battle of Fort Pillow.

If you lived in the North in April of 1864, you were on the fence with all this War business, and you read that 600 men were ruthlessly murdered while surrendering for nothing other than the color of their skin, you would be indignant, and rightfully so. If you had ten years of subtle indoctrination from Marx and Engels, and saw the entire war through a lens of Marxism, you may even march off to kill your brothers over a detestable lie.

-By Jean Lafitte

O I’m a good old rebel, now that’s just what I am. For this “fair land of freedom” I do not care at all. I’m glad I fit against it, I only wish we’d won, And I don’t want no pardon for anything I done.