When it comes to the history of the War Between the States, many are quick to cast the lens of importance upon larger and more famous campaigns, such as those of Lee and Jackson in Virginia, or Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” Battles like Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Antietam, and the like typically capture the historian’s eye and the public’s heart on both sides, contrary to some of the less known events and actions of the war.

When the conflict in the west is brought up, most assume, usually correctly so, that it pertains to the “Western Theater” of the war, which in academic and historical terms are the campaigns of Sherman and other Union forces in the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and the eventual march into Atlanta and the Carolinas. But, what does not come to mind for most is the far west of the war, the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the war, was the theater where the conflict was ultimately lost.

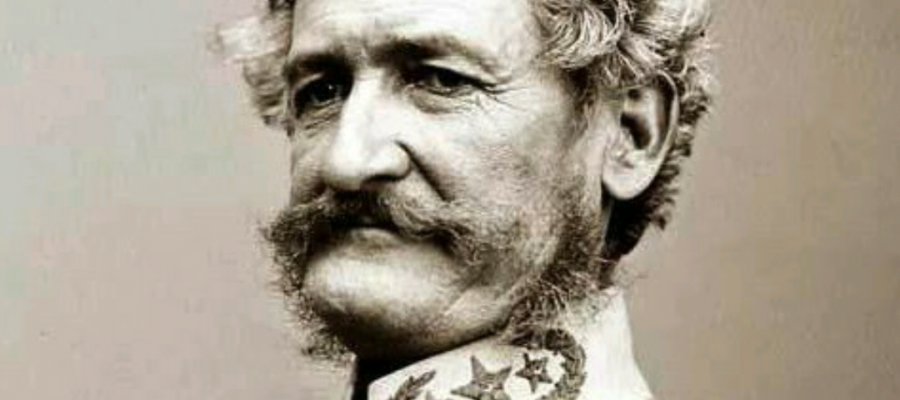

The infant Confederate government desired two commodities in chief; these were wealth and material for the logistical side of the war, and diplomatic recognition abroad. This was to both stifle Union response to their secession, and to achieve military or economic aid the way the Colonies had from France and Spain during the American Revolution. Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, a seasoned veteran of the 2nd US Dragoons, was a West Point graduate of the class of 1838, and had served in many US engagements, fighting against Indians and rogue elements of the frontier to the Mexican War and campaigns to pacify Mormons in the west. Having been stationed near Taos, New Mexico, prior to the outbreak of the conflict, Sibley was in a prime position to know the logistics of the federal army in the New Mexico Territory. From there, Sibley journeyed to Richmond, obtaining an appointment from President Davis, who was impressed with Sibley’s plans.

Davis, a longtime proponent of Manifest Destiny, saw the merit in a campaign in the Southwest to secure resources, supply routs, and manpower to support the war effort back east. After informing Davis of federal stockpiles of foodstuffs, animals, and war materials, he volunteered that he could recruit men for an army in Texas, and then arming the zealous young men with arms and equipment seized from federal arsenals scattered throughout the forts in New Mexico. Lt. Colonel John Robert Baylor had already mustered men, forming the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles, and had seized Fort Bliss, pushing CSA jurisdiction and claim up the Mesilla Valley. In Sibley’s mind, once his force had been equipped with the seized federal materials, they would seize Santa Fe and Albuquerque, upon which Southern sympathizers would further augment the force for a march into Colorado, taking therein prosperous mines of silver and other precious metals.

After that, they would march to the Pacific and seize the major ports along California’s coast, such as San Diego and Monterrey. The goal was, with this swelling of wealth from the mines of the southern Rockies and trade/access to the Pacific, the CSA would be able to fund a larger military with better equipment and supply chains. Furthemore, the expansion of CSA territorial boundaries would make it increasingly difficult for powers like France and Britain to not recognize it as an independent nation.

Sibley’s force mustered in San Antonio in August, 1861, where they trained and drilled for several months before marching west into El Paso, to rally with all outstanding CSA forces in the region before their campaign truly began. On the trail in the treacherous arid wastes of the Southwest, the volunteers of what came to be called “The Sibley Brigade” endured hardships unlike any other, their marches were plagued by want for food and basic supplies, parched and withering under a fearsome desert sun. While marching across some of the most hostile and forbidding terrain on earth, these young Texans and their cohort territorials endured harassment by Mescalero Apache raiding parties, resulting in something of a war on two fronts for the entirety of the campaign.

Sibley stuck to his intended goals marching his men west from El Paso into the Mesilla Valley, and then up the banks of the Rio Grande towards northern New Mexico and the gateway to Colorado. Meanwhile, Baylor took to the west, declaring himself governor of Confederate Arizona, and soundly defeating federal forces repeatedly in the southern portion of the Territory. Unfortunately, as the campaign wore on, lack of logistical support and stable supply train found the men of the Army of New Mexico haggard and gaunt. They were weary from enduring harsh elements and the constant encroachment of Apache raids and Mexican bandits, as well as pursuit by federal forces, having been reinforced by troops and volunteers from California and Colorado.

Despite inflicting heavy casualties on the Union and taking several key forts, the lack of supply and reinforcement, coupled with Sibleys’ resounding incompetence, the campaign’s momentum ground to a halt and faltered. Baylor had his rank and command revoked, upon Davis recieving word that Baylor ordered his men to kill all Apache they found, as well as reports of brutal treatment to Union prisoners of war. After the decisive battle of Glorieta Pass, fought in late March 1862, the battered and pessimistic Army of New Mexico retreated back to El Paso the way they had come in the preceding autumn. The retreat over such vast and hostile terrain brought a force back to San Antonio that was a skeletal reflection of the boisterous and enthusiastic force than the one that departed. The Brigade went on to see further action in Texas and Louisiana, with many veterans of New Mexico serving with distinction and valor in the battles along the Gulf Coast. But the New Mexico campaign, the dream of a Confederate grip on the southwest, went up in the smoke of the baggage trails along those lonely mountain roads.

The failures of the campaign can be placed authoritatively on those in leadership at the highest levels. While the rank and file fought admirably and valiantly, with some of the best statistical records and ratios of any CSA force in the war, they were led by senior officers who could not adapt to the challenges of the frontier the way the junior officers and enlisted men had. As the fighting dragged on, the losses of these junior officers in the field ultimately ruined the cohesion and capability of the Sibley Brigade to operate in any detached, combat effective way. Furthermore, Sibley’s constant drunkeness, obsession with vastly less important logisitcal questions like tents and frying pans, and general “wait and see” attitude, while not unexpected in an old veteran commander of his brand, was ultimately the chief reason the campaign would not succeed.

The trials of the trans-pecos and further west required the energy and creativity of a younger, more ambitious military mind. Sibley was content to cautiously wait for particulars to be met when speed and aggression were needed to secure victory. In addition, Sibley had his recruitment and mustering ads list the goals and objectives of the force being rallied, thus alerting federal elements in Texas and the Southwest of the CSA’s goals. In his zeal to recruit men for an ambitious campaign, Sibley idiotically informed the Union of their plans and intentions; the federal force he met in the New Mexico Territory had been increased nearly three fold as a result, and many Union stockpiles close to rebel hands were burned or destroyed.

His decision to march around Fort Craig and head north pinned his army between two Union armies, one in the north bolstered by Colorado men, and one in the south, bolstered by Californian reinforcements after Baylor’s removal and subsequent anarchy resulted in a loss of Confederate holdings in the southern half of the territory. Starving, dehydrated, deprived of horses and oxen, losing most of their wagons and supplies, and being almost spent on ammunition, the men of the Sibley Brigade had no choice but to abandon their cause and march back home to Texas, to mitigate their losses on a spent campaign, and to bolster the defenses of the Gulf Coast which had come under federal seige and seizure.

The New Mexico campaign serves to remind military historians of the importance of detail. Improper logistics, planning, and ineffective leadership will doom any force, no matter how zealous and skilled the fighting men may be. Small, backburner concerns for an army in Virginia can ruin an army from Texas fighting across thorn ridden dunes and deep, rocky canyons; applying a Virginian military mind to the badlands west of the Pecos proved futile, for all its experience and training. The mines of Colorado and ports of California may well have provided the Confederacy with the men, material, and support it needed to ultimately obtain independence; unfotunately, it will never be known, as the men in charge did not pay their due dilligence at the time, to the detriment of the able men under them, and ultimately the entire nation.

For Southerners, the fate of the Sibley Brigade and their campaign in New Mexico should serve to remind that zeal and ambition will not compensate for a lack of planning and material support; faith in God and the cause of our people will not be enough.

Are you gonna pull those pistols or whistle ‘Dixie’?

I sometimes wonder if Sibley’s force wouldn’t have been better used in securing Oklahoma, Kansas and Missouri.

As an aside, for me living in Texas, the Transmississippi Theatre is “local history.”

I have some family living out in New Mexico now, and when I’ve visited for extended periods of time I noticed that out there these days contrary to what I expected when I first went there they largely focus on their ancient Indian history to the mid 1500s when the Spanish came rather than the Wild West or its involvement in the civil war, and that’s likely because of their high Spanish an Indian demographics. The only place in the state that I saw that even recognizes the 1800s or the CSA involvement is the State Museum in Santa Fe. Beautiful state and I’ve only met kind people there though.

I have visited New Mexico and Arizona. I visited several of the battlefields of Sibley’s campaign. I felt completely at ease there. Almost like I was in West Texas. The food and culture aren’t that much different from Texas. A lot of Texans have settled in eastern New Mexico, since the 1870’s. Yankee tourists sure stuck out, though. Like they do in Texas and in the rest of Dixie.

You are absolutely right. Folks doubt me when I say that both states, especially in the southern parts, are more or less just extensions of West Texas. They call it the “Tucson-Las Cruces-El Paso” cultural and economic corridor for a reason.

Great article. It’s interesting to note, that the butterfield trail was still a yankee toll road throughout the war, modern day lnterstate 10 through NM and Arizona. I’ve read about a lot of good civil war battles to control that road, especially out of arkansas.

I lived and worked in Riodoso, NM, one summer, home of “Billy the kid” (Lincoln county) just a little north of las cruces and El Paso, me and a tough old yankee jackass, raked pine needles and fed a chipper all day, we primarily cleared lots for Texans mountain retreats.

At 7000 ft elevation, in the month of July, all the hot air from the western dessert creates 100s of lighting strikes daily and torrential rainfall, all over the town of Riodoso. It’s really incredible.

It’s also home of “Smokey the Bear”. (Lincoln county) high fire danger there.

Keep the excellent articles coming. Thank you, and may God heal this land, and render our enemies powerless.

Thank you for the kind words, there will be more to come

Yeah I’ve never really be in West Texas other than driving through there to New Mexico, but they seem very similar. Its very relaxing out there, and the native people I’ve noticed are very laid back as well.

The culture is very different from what I’m used to in TN, but still very pleasant. I’m right with you on Yankee tourists sticking out, we can tell them here as well in Sevierville or any of the other tourist parts of the state. They’re always the ones yelling an complaining when something isn’t ready right then an there, what a miserable bunch.

New Mexico was the first victim of “Californiacation” in my opinion. Colorado fell a decade or so later, and now Arizona, Idaho, and Utah are on the road too.