This is the second part of a three-part series on Lessons from Iranian Nationalism and focuses on the transition of interwoven leadership cultivation, as covered in the first part of this series, to the creation of a functioning nationalist movement at the local level. It covers how Iran builds a movement from the ground up, studying Iran’s greatest success story, Hizbu’llah (aka, Hezbollah).

No nationalist movement can succeed without community engagement. In order to win the strategic objectives of the movement, the nationalist entity needs to show that the movement is designed for the benefit of the people it purports to serve. The National Socialists of Germany and the Fascists of Italy provided a number of social welfare and community benefits to the German and Italian people respectively. The Irish Republican Army was not in a position to provide broad social welfare benefits, but they immediately provided order when post-conflict chaos ensued. Successful nationalist movements sell the people on their value for those people.

In order for Southern Nationalism to advance, ordinary Southerners need to believe that an independent South is the better option than a continued relationship as a subordinate vassal state to Northern elites.

This means that we need to show them that we – Southern Nationalists – can replace the relative comfort of their current station. This can be achieved by either (a) showing we are better or (b) the current situation will devolve and soon be uncomfortable. In fact, a coherent communications strategy will require both. But that is a topic I will explore in part three of this series. Organizationally, ordinary Southerners need to believe that we can supplant the current federal government or sell them on a solution shows we can manage a transition from federal government to state-centered/locally driven decision making and resource disbursement.

The focus of this piece will be that which Iran and more importantly, its non-state strategic ally, Hezbollah, was able to achieve as a model for nationalist movements elsewhere: the creation of the functioning Alternative State.

Despite what you may have heard about Hezbollah, it is not a terrorist group. Hezbollah is a religious-nationalist paramilitary group designed to preserve a unique people, the Lebanese Shi’a. It is an organization that has grown from an insurgency to a legitimate political entity with elected officials in Lebanon. On the one hand, Arab Nationalists and some Islamists embrace Hezbollah’s steadfast commitment to its anti-Israeli and anti-Western strategies. On the other, these same groups seek the eradication of Shi’a Islam and have little respect for Hezbollah’s main constituency, the Lebanese Shi’ite people. They correctly view Hezbollah as an extension of Iran.

For Southern Nationalists, the relationship of Hezbollah with other Islamic movements may seem familiar. Southern Nationalists are used to sharing and working with broader White Nationalist groups, only to have those same groups disregard Southern Nationalist desires for a Free Dixie. As such, building our own, unique organizational structure is a preferred course for Southern Nationalists – as Hezbollah was capable of achieving in the late-1970s when Arab Nationalists and Islamists ignored and discounted their unique needs.

To understand Hezbollah, one must understand its history. Hezbollah was an outgrowth of several factors in post-colonial Lebanon in the 1950s. Without going into too much detail, Lebanon emerged as a bifurcated state, comprised of Sunni and Christian centers of power with Christians as the majority in the 1950s and 60s. Generations of French leadership had cultivated French Christian bureaucratic dominance. Still, the Muslim population of Lebanon was predominantly Shi’ite at that time, but in the main urban environments – near the seats of power and wealth – Sunnis dominated. As Shi’ites began moving toward the cities for work, they began to see their relative deprivation from slums called the “Belts of Misery.” This led to a growing determination to galvanize and form political unions by some Shi’ite religious leaders. The movement gained very little traction, as larger affairs in the Arab world dominated the 1960s and early 70s.

Then a cataclysmic series of events occurred, laying the foundation for Hezbollah.

After the creation of Israel and several subsequent battles culminating in the acquisition of the West Bank in 1967 during the Six Day War, Palestinian refugees poured into nearby Jordan. At first, the Jordanians accepted their fellow Arabs. In 1964, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) formed in Jordan and by 1967, the PLO was capable of launching guerilla attacks with greater frequency. Having been beaten by Israel and faced with a fast-growing Palestinian refugee population, Jordan was happy to help the PLO achieve its objectives. However, the Soviet Union began to see an opportunity to erode American power in the Middle East by supporting leftist, anti-colonial, anti-religious, and anti-monarchy parties. A significant portion of the Palestinian people gravitated to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) – a Marxist revolutionary political group loosely affiliated to the PLO, but independent.

The PLO, competing for resources to wage its war against “America’s Greatest Ally,” also made overtures to the Soviet Union. The Soviets were happy to assist. However, to receive Soviet support, Palestinian leaders had to condemn the Hashemite Royalty as illegitimate and condemn conservative Islam. This not only enraged King Hussein of Jordan, it also infuriated conservative clerics within Jordan who felt the sudden embrace of Marxist-inspired modernity was a betrayal. Radicalized members of the PLO began attacking Jordanian police as extensions of an illegitimate crown. The Jordanians had enough. They launched a series of attacks in September 1970 (“Black September”) intended to crush the PLO and any other aligned movements. They also sought to remove the Palestinian refugees from their borders, seeing them as creating an independent nation within their state borders.

The Jordanians succeeded. With nowhere to go, the Palestinians began heading for Lebanon, where refugee camps were established with the help of Syria. Suddenly, the Lebanese Shi’ite population was no longer the largest Muslim body within that country. Furthermore, the Shi’ites were now surrounded by equally impoverished Palestinians who were competing for resources. Unlike the Palestinians, however, the Shi’ites lacked a powerful benefactor; the Palestinians had both Syria and the Soviet Union. They also lacked the political clout at the centers of power, which were dominated by Christians and pre-Palestinian Sunni Muslims. The near overnight imbalance greatly threatened the Shi’ites of Lebanon.

Only a few years later, in 1975, while ordinary Lebanese Shi’ites were being crushed, Lebanon headed into a Civil War between Christians and Palestinians. As this was going on, Shi’ites found themselves with no allies at all. Although they formed defensive militias of their own, the Shi’ites lacked substantial training. Maronite Christian militias targeted the more vulnerable Lebanese Shi’ites rather than the more experienced and better trained Palestinians. Then came a “gift” from Iraq.

In the late 1960s, the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party in Iraq, led by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, began implementing a number of socialist economic policies and secular reforms led by his protégé, Saddam Hussein. A decision was made to clear out the Shi’ite religious centers of Najaf, Iraq. There, radical Shi’ite religious scholars, like Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr and the exiled Ruhollah Khomeini, taught Shi’ite theology and blended it with political ideology. A pan-Shi’ite identity was forming – a threat to the Sunni-led Ba’ath Party. As such, the Baathists began expelling Shiite religious students and leaders. Many of those religious leaders now found themselves returning home to war torn Lebanon. For his part, Khomeini would be expelled in 1978.

Trained, intelligent, and with a brotherhood defined by shared experiences of learning and sacrifice in Iraq, Lebanon’s new generation of Shiite clergy arrived into a leadership vacuum at the height of chaos. They immediately organized their constituencies into religiously inspired militia groups emphasizing a new paradigm in the art of war for the region: the Martyr. The Hizbu’llah – “The Party of God” – emerged.

But although Hezbollah enjoyed religious and nationalistic zeal for the Lebanese Shi’ite people, it still lacked training, weapons, and financial support. Then the Shah fell and the Grand Ayatollah Khomeini emerged. The clerical leadership that formed the nexus of Hezbollah, led by Abbas al-Musawi, suddenly had a potential powerful benefactor in the new government of Iran. The Grand Ayatollah Khomeini did not disappoint.

In 1982, Israel chose to invade Southern Lebanon, ostensibly to restore order and clean out pockets of Palestinian guerillas who exploited the Lebanese chaos to attack Israel. What they did, however, was come down hard on the dominant Lebanese community in South Lebanon, the Shi’ites. The Israelis would frequently cut off water, food, and electricity of villages seen to be sympathetic with the Palestinians as punishment for collaboration. The Shi’ites may or may not have sympathized with the Palestinians, but they did not support them, either. The two were competitors for power. The disproportionate response of the Israelis led to thousands of Shi’ite deaths which now enraged Iran and the radicalized Shi’ite world.

Seeing his fellow Shi’ites attacked from all sides, especially by Israel, Khomeini sent fifteen-hundred Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) members to Lebanon to advise and train Hezbollah. At the same time, through Arab intermediaries, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) arrived to teach Shi’ite and Palestinian warfighters how to immediately level the playing field through the use of improvised explosive devices constructed of easily accessible goods. PIRA designed pipe-bombs became so prolific, that it slowed Israeli incursions to a crawl.

As both the Palestinians and Shi’ites found common cause in the Israeli enemy, Muammar Gaddafi opened training facilities in Libya, ran by experienced operatives, notably the IRA, to immediately bolster the fighting capabilities of the two parties. Lebanese snipers and bomb technicians were shipped back to Lebanon via Iran and then Syria. For his part, aware of the Irish contribution to Shi’ite support, the Grand Ayatollah Khomeini renamed the street upon which the British Embassy resides from “Winston Churchill Street” to “Bobby Sands Street.”

While the Libyans sent newly trained operatives to stem the bleeding, the IRGC set to work on a much grander mission: they were to build a religious and nationalist inspired army that could not only win a war, but sustain a peace. The IRGC was a phenom in its own right. The fact that a military enterprise of deeply loyal, highly religious soldiers were ready to deploy in such a large number only three years after the ascendance of Khomeini from Iran was extraordinary. But what they built in Lebanon – out of nothing but heart – deserves praise. By 2000, Hezbollah went from a group of religiously inspired martyrs to the first Arab force to defeat Israel.

How did they construct Hezbollah? The Iranians helped build upon their unique brand of local activism coupled with military acumen. They built a mini-Revolutionary Iran in Lebanon. And they did so locally.

Go Local: Interdependent Autonomy

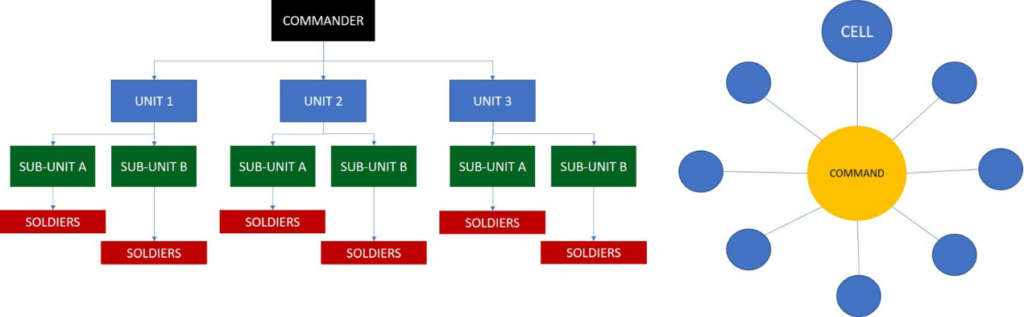

Like Iran’s broader structure to protect the Revolution from external actors, Hezbollah is constructed in a manner that is more akin to the honeycombs of a beehive than linear or hub and spoke models of command and control. By that I mean, unlike linear command and control systems in a traditional Western military (General > Colonels > Majors > etc…) or like other Nationalist insurgencies, like the IRA or even the Vietcong, whereby a central command system has a number of independent cells, Hezbollah is best characterized as having that which I will call “interdependent autonomy.”

Figure 1: Traditional Military – Hierarchical Linear Command Model – and “Hub & Spoke” Insurgency Model

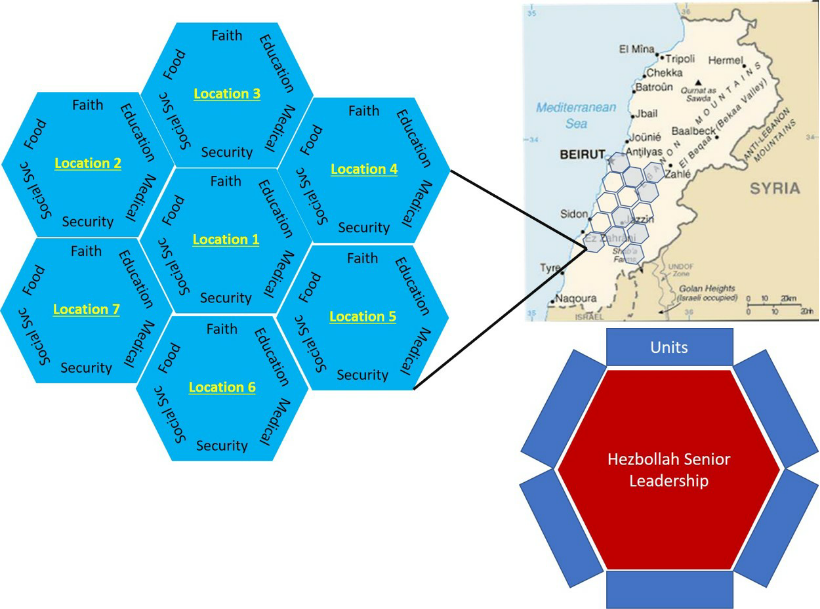

A command structure at the center exists. It is the heartbeat of the hive. Hezbollah takes strategic direction from senior leadership to achieve military and political goals. Meanwhile, at the operating level, each honeycomb is largely built to be self-sufficient, but supportive of neighboring honeycombs. The hexagonal cube offers protective rigidity. After Hezbollah, like Iran, develops talented leadership, it employs that leadership in ways that can support the local community, while building a loyal fighting force.

Figure 2: Hezbollah’s Honeycomb Structure with Senior Leadership at the Core

Despite depictions in the 1980s of Hezbollah, the crazed Shi’ite martyrs with scarves around their faces, Hezbollah is quite sophisticated. It provides medical services to the local needy. It provides food banks. It provides an education that is far more advanced than Salafist madrasahs. While it is true, some Hezbollah-run education facilities are infused with anti-Western and anti-Israeli rhetoric, they also teach real skills. Math, history, geography, and science are core subjects taught.

Describing a Hezbollah school in 1997, the L.A. Times reported: “There are no yellow flags with the Hezbollah logo of a raised Kalashnikov assault rifle. No murals of Hezbollah ‘martyrs.’ No political slogans.” Unlike Ḥarakat al-Muqāwamah al-Islāmiyyah (HAMAS) with its emphasis on totting around children in green martyr headbands screaming “Death to Israel,” Hezbollah is seeking skills upon which future generations of Lebanese Shi’ites can build a better, holistic future – all of which is local.

The LA Times depiction was written more than twenty years ago – a generation of students have since passed through a Hezbollah private school and most likely, their children are going to one now. Imagine where Southern Nationalism could be today if a generation of children were raised in an environment that taught hard skills and a veneration for Southern history, culture, and identity. Such schools would be invaluable.

As stated earlier, medical care is another core component of Hezbollah’s strategic construct. It yields a significant advantage to the organization’s political and military aims. The first advantage is obvious: Hezbollah ingratiates itself with the local people to whom it provides medical care. It is hard to hate someone who saves your child’s life or cares for you when you are ill. The second advantage is also obvious, but more important to the broader strategic capacity of Hezbollah. Providing health care strengthens the medical capabilities of Hezbollah’s war fighting capabilities. The local doctor or nurse can quickly become a medic. This is of enormous value. But the bigger value is the infrastructure that comes with the local medical support.

Insurgencies are generally capable of recruiting and retaining individuals with medical talent. That is not the problem. The bigger issue for any military is the number of field hospitals necessary to treat the wounded. Through building small clinics, Hezbollah has created a network of facilities that can quickly become field hospitals when defending its territory. More importantly, because of its honeycomb structure, Hezbollah can move resources quickly to the field hospital with the greatest need, i.e., closest to the fighting.

This gets to another facet of the brilliance of Hezbollah’s design: its supply chain network. Louisiana native and LSU Alumnus, Marine Corps General Robert Barrow, famously stated in 1980, “Amateurs talk about tactics, but professionals study logistics.” It was part of a broader strategic shift to refocus the Marine Corps to a military unit previously reliant on other services for support to one capable of bringing supplies and support to the fight on its own. Perhaps unironically, Barrow, was the Commandant of the Marine Corps as Marines were being stationed in Beirut.

The interconnected web of support that the beehive model provides enables the rapid deployment of supplies, weapons, and men to swarm into a location quickly, with a ready base of support. This gives almost every facet of Hezbollah charitable activity the added ability to support wartime activities. Food banks become mess halls… local clinics become field hospitals… local schools become headquarters and communications facilities… free buses become rapid military transports… clothing distribution sites become weapons depots. Worse, the political fall-out of attacking a “food bank” or a “school” is immediately exploited by Hezbollah as propaganda.

Whereas I have confidence that the South can peacefully secede through the use of the existing American political infrastructure, it would be in Southern Nationalist’s best interests to begin building a network of schools, field clinics, food banks, clothing distribution sites, and other services for the indigent. Again, some of these services need not start out big. They can begin as simple sandwich stands for the local working class. Networks of parents, especially mothers, can provide pro-Southern, after-work care for working parents. A registered nurse can provide free blood pressure checks to help identify potential causes of one of the South’s biggest killers, high blood pressure. Volunteers can fix the homes of the elderly.

Starting out small, with a “Southern Aid Society” would be enormously beneficial, not only to the people who need the assistance, but also the organizations seeking Southern independence. Basic political good will would go a long way. Building a parallel political infrastructure through invaluable networking and structural achievements would begin to emerge from such an aid construct. These should be local and constructed to support allied local aid groups. Finally, they should be clear in their goal: the assistance of the Southern people and the propagation of the one true God.

In the next section, I will cover the unique communications of the Iranian Revolutionary movement, with a particular emphasis on the speeches and personality cultivation of the Grand Ayatollah Khomeini. The importance of messaging is not only critical for nationalist movements to perfect, but message discipline is essential. A carefully orchestrated communications platform can earn respectability for the cause, recruit additional talent, build political will, and earn the funds necessary to build upon one mission: Southern Independence.

The son of a recent Irish immigrant and another with roots to Virginia since 1670. I love both my Irish and Southern Nations with a passion. Florida will always be my country. Dissident support here: Padraig Martin is Dixie on the Rocks (buymeacoffee.com)