The formation of an effective fighting force that was ultimately capable of defeating the British and securing Irish independence was far more complicated than most modern scholars on insurgencies can comprehend. After sixteen previous recorded attempts to secure Irish independence through force, however, the Irish eventually got it right. What changed? What lessons were learned in the preceding attempts to win a war with the world’s most powerful military in its own geographic backyard? This piece will address some of the lessons learned by Irish Nationalists at the turn of the 20th century.

Before I begin, let me state that the purpose of this piece is not to inspire violence of any kind. This is written simply to explore a unique aspect of Nationalist history. The Irish case, as stated in the previous piece, shares exceptional lessons that can and should be explored further by Nationalists around the world, and especially Southern Nationalists. The continued war – cultural, economic, and physical – against the Southern people by a Marxist and Globalist cabal shares extraordinary similarities to the Irish example just prior to ascending to her own freedom. These lessons have significant utility for the sake of organizational development and strategic comprehension.

The Easter Rising of April 1916 is often seen as the catalyst for the Irish War of Independence. While that is partially true, the martyrs of the Easter Rebellion failed in their core objective: exploiting World War I to inspire a National revolt throughout Ireland that would secure Ireland’s freedom. In large part, the great failure of the Irish Volunteers who enjoyed some initial successes in Dublin during that fateful week (24-29 April 1916) was the notion that it could fight the British military and by extension, its loyal Irish counterparts, directly. While most understand that the (old or original) Irish Republican Army eventually chose a guerilla war to defeat the British, how the Irish got to that point was hardly a foregone conclusion even after the failure of the Easter Rising.

Many within Irish Nationalist circles believed that a guerilla war would be unnecessarily bloody and may delegitimize the independence movement. Eamon de Valera, the future Prime Minister of Ireland and an Irish Volunteer at the Easter Rising surrender, was notable in his objection to guerrilla warfare. Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Fein (“Ourselves Alone”), preferred passive resistance (e.g., boycotts of British goods and businesses). Meanwhile, many more practical Irish Nationalists, such as Tom Barry, Michael Collins, Charles Hurley, and Richard Mulcahy, recognized that armed conflict was upon them and the best way to fight was through the use of smaller, more mobile local units.

But what really brought the Irish to use and arguably perfect the “flying column” was simply a matter of constraints. Unlike previous and subsequent insurgencies, the Irish had to figure much out on their own. The North Vietnamese, for example, enjoyed significant Soviet support in both weapons and training. The Afghan Mujahedeen was extensively supplied and trained by American operatives. By contrast, much of what the Irish would learn and do was born of self-taught lessons, many of which was gleaned from the writings of their close anti-British ideological allies, the Boers.

At the time of the Irish War of Independence, the South African Dutch descendants who had fought an eventual losing war against British aggression in their homeland, were crucial to the development of the Irish flying column. The Anglo-Boer wars had only concluded fourteen short years before the Easter Rising. However, even before the Anglo-Boer Wars began, Irish and Boer Nationalists shared a great deal of correspondence and sympathy for one another. In Bruce Nelson’s Irish Nationalists and the Making of the Irish Race, the author dedicates an entire chapter (Chapter 5: “From Connemara to Kaffirland”) to Irish-Boer Nationalist relations. In it, he describes Arthur Griffith as having “close and direct ties to Afrikaner nationalism” (pg.133). Support for Afrikaners was so strong in Ireland that Irish Member of Parliament, Patrick O’Brien, waved the Vierkleur (the flag of the South African Republic) and in a speech “expressed hope that ‘instead of firing on the Boers, Irish regiments in South Africa would fire on Englishmen” (pg. 134). Consequently, many of the military lessons of the Boer Kommandos, small bands of armed men who engaged the British with great initial success, were shared with the Irish in the lead up to the Irish War of Independence.

However, unlike the Boer Kommandos, an originally state sanctioned body designed to assist in the collective defense of the various Boer and later British territories of South Africa, the Irish had no such training. The English always viewed the Irish with suspicion and ensured that arms were denied the Irish masses. Meanwhile, military training was limited. Many of the Irish, like Tom Barry, would learn military tactics in the service of the British Empire, but even these lessons were limited and myopic. Few Irish Nationalists enjoyed any significant military rank beyond lower Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs). The Boers, by contrast, had a fairly large body of men with some field grade officer training (veldkornets) and the Kommando units themselves were headed by experienced senior NCOs. Still, broader strategic and tactical experience was greatly limited.

It is important to note that rarely, if ever, are revolutions led by senior military officials for the sake of creating an independent state. Even the American Revolution experienced this problem. The American revolutionaries enjoyed a number of officers with military experience from Europe, but none were higher than field grade officers. Von Steuben never exceeded Captain (despite a misrepresentation as a Prussian Lieutenant General). Horatio Gates was a British Major. Casimir Pulaski was probably the most accomplished military officer from Europe. Pulaski attained the rank of Colonel and enjoyed considerable success against the Russians before coming to assist the Americans. Still, it was Washington, a Virginia militia colonel with marginal, mostly disastrous battle experience, who led the Continental Army. The irony of revolutionary movements is that the one group with arguably the greatest concentration of senior military officers to seek secession, the South, lost their war militarily. This is a point that I will address at the conclusion of this piece.

Both the Boer and Irish independence movements were no different. “General” Christiaan Rudolf de Wet, a hero for his people, never held a rank higher than a field cornet (about the equivalent in rank to a First Lieutenant) prior to his fight against the British. The Irish, however, would use this lack of experience to their advantage in the construction of a unique fighting force. Given that the vast majority of fighting Irishmen who had military experience never exceeded the rank of Corporal, the Irish flying column was perfectly constructed for maximizing the benefits of squad level, asymmetric attacks on a British force that was not used to such “hit and run” actions. The development of the first strategic corporals emerged: men whose small tactical operations were coordinated with cumulative strategic effect in mind.

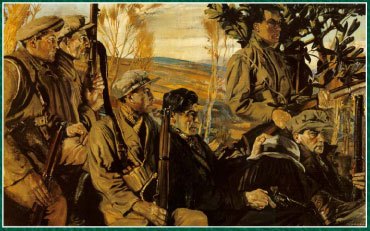

Ernie O’Malley and Tom Barry both wrote autobiographical accounts regarding the use of flying columns – small bands of disciplined guerrillas who lived and fought locally. They describe the challenges of organization. Neither man ever led a single operation with more than two dozen men. They chose targets that undermined local confidence in British rule. Coupled with a previous investment in Irish Nationalist cultivation (i.e., Irish newspapers, Irish language schools, Irish businesses), the flying column exploited a key vulnerability in the British hold on Ireland. The flying columns targeted trucks, isolated caravans, police headquarters, and local prisons. Meanwhile, the Irish did something that the Boers did not: Irish Nationalists immediately organized and instituted parallel institutions to British institutions at the local level after an attack.

Irish political and military coordination was crucial to the success of its revolution. As a police headquarters was destroyed, Sinn Fein courts and local deputies immediately stepped into the temporary vacuum. The development of these parallel institutions took almost two generations to achieve. Men who were trusted members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret society of Irish patriots, were selected and groomed for roles as magistrates, judges, tax collectors, etc.

Since the flying column was also a local military organization, trust was easy to maintain. In fact, the British government – not unlike the American government’s current tactics against those whom they perceive to be a threat today – was to exploit native caution regarding “foreigners” by sowing the seeds of distrust through rumors. The ubiquitous Ernie O’Malley, who fought all over Ireland throughout the War of Independence, describes his primary challenge as a key Dublin based organizer with local fighting units. Rumor mongers often sowed the seeds of doubt upon his arrival, claiming O’Malley was a double agent of the British.

In his book On Another Man’s Wound, O’Malley describes how he would arrive to a flying column to coordinate an attack for the sake of achieving a national strategic objective, often at the behest of Michael Collins. Someone from within the flying column would spread a rumor about O’Malley, usually in relation to his remarkable good luck or his lack of substantial prison time. O’Malley for his part was not only shot several times, he was arrested and either escaped prison or was released on bizarre technicalities on several occasions – not without a great deal of personal pain. The rumor would erode confidence in O’Malley and his mission. The same Irish accuser would then inform local British or loyal Irish military units of the plans, only making it seem as though O’Malley’s arrival was the cause of the collapsed mission. O’Malley describes the frustration he often felt at such accusations.

To combat this tactic, Michael Collins, chose to use his significant intelligence resources – frequently local women – to get to the root of the rumor and mission failure as quickly as possible. More often than not, the rumor originated from an individual who was a compromised member of the flying column. Usually, a family member was arrested and the other had to act in order to save his kin. The British were not above torturing the mothers and sisters of known revolutionaries, burning down their homes and sexually degrading the females. The threat alone was often enough to turn an Irish flying column fighter into a British agent. Regardless, Collins, who was frequently accused of being a traitor and member of British MI5 himself, came to the conclusion that the one making the accusation of disloyalty was usually the actual rat (Michael Collins and the Women Who Spied for Ireland, by Meda Ryan). Collins sometimes allowed local units to dispatch the disloyal member as they deemed fit – sometimes leading to executions and at other times leading to neutralizing the hold the British held over the compromised member’s head. However, Collins would most often order their execution as traitors to the cause.

The construction of the flying column was given a great deal of fluidity. Small arm tactics depended greatly on the fighting environment and even the demeanor of the community within which the flying column would operate. Again, not unlike the South, the Irish are not monolithic. Accents vary widely. Humor, stories, religious beliefs, and local history is crucial to the Irish people. The men of Cork had as much a difference in culture with those of Roscommon as an Alabamian might have with a North Carolinian. Both Southern… both likely Evangelical Christians… both sharing some historical grievances with the American Empire… yet different in demeanor, accent, and historical outlook on some issues.

What bound the men of Ireland together in the fight was the fact that all of the fighting men of the Irish Republican Army knew that other men in Cork, Tipperary, Kerry, Louth, and elsewhere were fighting and dying – just like them. They knew they were employing similar, small raids and melting back into their farms and villages. They were all committed to a cause. Thus, lessons on small tactics that worked well in one spot were easily adopted by others, because they knew that all of them were suffering and fighting a juggernaut together. Again, an investment in Irish Identitarianism was crucial to the interconnected success of the Irish fighters throughout the War of Independence.

One other element of the successful Irish military campaign was introduced by Michael Collins: “The Squad.” The Squad was an intelligence and counterintelligence operation that depended heavily on hand-selected Irish Nationalists – surrounding “The Twelve Apostles” (twelve hand selected operators close to Collins). It was unique at its time. Whereas the flying column made small hit and run attacks that eroded confidence in British control of the rest of Ireland, the Squad made bureaucratic replenishment for the British nearly impossible.

The primary mission of the Squad was targeting British intelligence operatives for assassination. This was not abnormal. Wars typically have a seedy, unpleasant spy-vs-spy parallel war. Such battles between espionage entities are rarely covered. They are nasty. But Collins introduced a new level of barbarity to the fight that likely won Ireland its independence.

The cut-throat brutality with which Collins led Squad operations was an extension of his background. Collins was never a soldier. He was a former member of the British civil service and unlike his Irish Nationalist peers, he had a significant business background – especially in accounting. Understanding the importance of accounting and mundane technocratic management to British rule, the Squad targeted mid-level managers of the British bureaucracy managing imperial affairs in Ireland. Often, working for a brief period of time in Dublin as a regional manager of a Customs House, for example, was a stepping stone toward greater civil service opportunities within the Empire. The allure of the position brought some of England’s finest technocrats who were very effective at running British interests in Ireland. Collins began assassinating these fine technocrats and as such, created a bureaucratic management vacuum.

Michael Collins knew from his time in big house accounting firms in London that the senior managers were largely symbolic. Senior civil servants were typically minor aristocracy of little practical use. Rather, by targeting the middle managers, he not only eliminated an effective officer of British rule, the threat of assassination made other managers reluctant to fill the vacancy. Without bean counters, logisticians, customs officers, and other vital British bureaucrats, Michael Collins was able to deprive the British of crucial governing assets at a time when they needed it most.

Additionally, the Squad used its mandate to enforce counterintelligence operations with deadly precision. The targeting of British agents – Irish fighters turned by the British – was crucial to the war effort. This was cold work. Men who were raised with the duplicitous culprit had a hard time putting a trigger to their kinsman’s temple. The Dublin based Squad had no such allegiances to anyone except the Irish Nation. Devoid of the emotional connection with traitors that is common in war, the Squad was able to eliminate threats to the integrity of flying columns – sometimes without the flying column knowing.

Again, the Squad was made possible by an investment in Irish Nationalism that pre-dated its formation by at least a generation. These men spoke Gaelic because Irish Nationalists before them made sure the language did not die. They knew each other through secret societies that met carefully. They avoided hot heads and often seemed too cozy with British society, making it easier to blend. But rather than become coopted by the comforts of the Empire, Irish Nationalists were so deeply ingrained in their mission that they could salute the Union Jack while harboring deep resentment toward its very presence in Ireland. Such discipline was never confused by other Irish Nationalists, most of whom were capable of singularly remaining focused on the goal: A Free Ireland.

Finally, one other key element of the Squad was the extensive intelligence network that Collins used to secure Irish independence. In The Squad: and the Intelligence Operations of Michael Collins, T. Ryle Dwyer, the author describes the extent to which the Irish relied on a network of information gatherers that extended from lower level bureaucrats to pub owners to priests. The development of intelligence networks started well before “The Big Fella” (Collins nickname) ascended to his leadership role. The intelligence networks derived from Irish language, dance, and cultural schools that were established decades before the war began. Irish Identitarians built a ready body of intelligence operatives that played a crucial role in the War of Independence.

Cumulatively, the Irish flying column targeted British and loyalist Irish units by virtue of the intelligence garnered from Collins’ team. Meanwhile, the Squad deprived the British of critical management resources and intelligence assets. The totality of the war operation was that the British seemed to get hit by a never-ending hornets’ nest of stinging, small attacks directed at its capacity to run its imperial operations inside Ireland. Regardless of where the hit landed, a ready parallel state function was ready to step into the vacuum created by either death or fear.

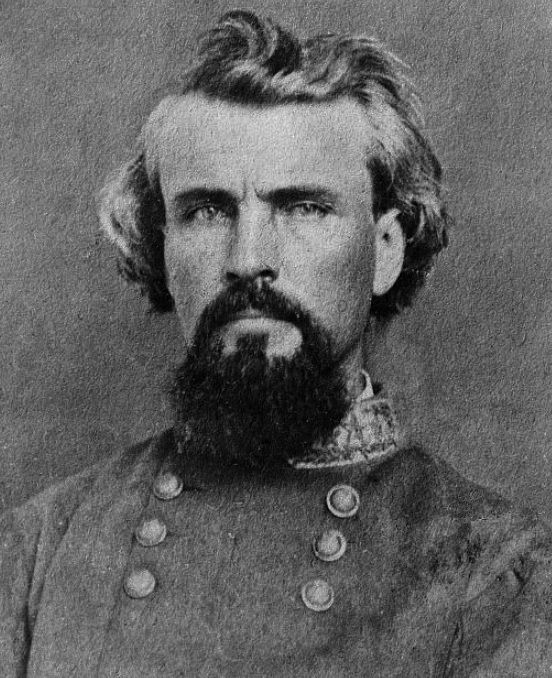

Returning to the South’s seeming advantage of the mid-19th century, the Irish example seems to place it into question. The South had a great deal of senior officers within the ranks of the American military. These were valuable men with extensive training. Many were veterans of the Mexican War. However, this may have ultimately hurt the South. The decision to fight the Yankees like Yankees ultimately proved disastrous. The men who were most successful against the Northern invaders were those who were not handcuffed by such training or thinking. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s tactical speed – “the firstest with the mostest” – can best be described as the defining strategic principle of the flying column. Likewise, Stonewall Jackson, who had the luxury of developing his military concepts outside of the regular army. While a professor at the Virginia Military Institute, a relatively new college at the time, Jackson was not infected by the group think of military leadership in the mid-19th century U.S. Army. His tactical concentrations on discipline, speed, intelligence gathering, and obscuring unit strength are all crucial principles to the flying column.

I would argue that the South’s high concentration of West Point trained senior military leadership – from Davis down – was its undoing in the 1860s.

One can only imagine the outcome of the war if, rather than fighting massed battles of troops at places like Shiloh and Gettysburg, the South had drawn confident Union armies into the interior, only to be decimated by small raids and an intelligence network that targeted Washington, D.C. wartime bureaucrats. While the guerrilla warfare strategy is somewhat controversial among “Civil War” enthusiasts, it is important to note that the South had a significant advantage to play on their home turf. The Afghan Taliban and the North Vietnamese did not win any major engagements against superior American forces, yet both won their wars. If the goal is independence, then the means need not look pretty to be effective.

Should a military engagement ever be required again, (God forbid) investments in small, local tactical fluidity that exploits the strengths of the South’s large pool of enlisted veterans would be crucial to its success. The development of an intelligence infrastructure comprised of ruthless men would be necessary. Still, all of this would fall flat without the development of a Nationalist consensus of the broader Southern people. Absent that investment, any attempt to militarily secede would fail. Thankfully, the push for political secession solutions, such as Calexit, make the possibilities for peaceful secession all the more likely. Southern Nationalists would be better served to co-opt existing bureaucratic entities rather than targeting them with violence. In other words, the Irish in 1919 had far fewer options for independence than the South in the 21st century. The former required military action to achieve independence; the latter simply needs to build political will.

In Part III of this series, I will cover the political and parallel state functions that the Irish Nationalists needed to develop in order to not only win their War of Independence, but also necessary to win the peace.

The son of a recent Irish immigrant and another with roots to Virginia since 1670. I love both my Irish and Southern Nations with a passion. Florida will always be my country. Dissident support here: Padraig Martin is Dixie on the Rocks (buymeacoffee.com)

Great article again, sir. Well done. You write:

I reluctantly agree. Remember the Maury Gunboat War?:

https://civilwarnavy150.blogspot.com/2012/02/

The Irish Genocide is the reason my people are over here. Ellis Island arrival 1856 from Athlone, Éire.

–

http://www.irishholocaust.org/home

–

http://tlio.org.uk/land/land-rights-history/irish-holocaust-the-mass-graves-of-ireland/

–

http://www.irishhistorylinks.net/History_Links/IrishFamineGenocide.html

–

https://www.irishcentral.com/news/irish-famine-genocide-british

Éire was lost long ago, now the same “Famine” is being enacted against America. Read this article with particular care –

http://tlio.org.uk/land/land-rights-history/irish-holocaust-the-mass-graves-of-ireland/

A land of debt-serf renters who are about a month away from financial ruin and a couple from the street. Public health and wellness emergency orders are more closely related to the National Security Act of 1947. Before this, there was the U.S. War Department. Now, the war is against the notion of what America used to be – if it ever was to begin with.

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/national-security-act

–

https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-anti-federalists-and-their-important-role-during-the-ratification-fight

P.S. I’m abundantly aware of the irony of my name and the content of this post.

http://classics.mit.edu/Plutarch/lycurgus.html