Foreword: This essay was originally featured on the old website before said site’s deletion from WordPress. This is a revised version of that essay.

The South features a long and cultured history with much to admire. The antebellum period receives the most admiration as a historical period in the eyes of Southern Nationalists and many Southerners in general. However, the much maligned Jim Crow Era deserves more admiration than currently received, and an unbiased historiography, from a Southern perspective, reveals the benefits and political prosperity said era provided Dixians. This essay’s purpose is to assert that the Jim Crow Era was Dixie’s “Golden Age,” so to speak, and will provide a general timeline and analysis of segregation’s reign over the South as well as the implications of having such a system, detailing the Gilded Age, Progressive Era, the Great Depression and World War II, and, ultimately, the Civil Rights Era which ended Southerners’ control over their homeland.

The Gilded Age arguably started with the conclusion of Reconstruction and the implementation of the Compromise of 1877. Following that tumultuous period, Southerners began the process of reclaiming their home’s political system through the implementation of the earliest pieces of Jim Crow legislation. However, Negroes did continue to experience representation within local and some state level offices, but they were excluded from higher state level and federal participation. Additionally, Dixie rose as a powerful political bloc within the Empire as the Solid South, and the federal government allowed Southern governments to act without issue so long as they no longer violently resisted the Empire, establishing Dixie as a country within a country.

Life during the Gilded Age, though relatively an improvement over Reconstruction, experienced a great deal of hardship. The South, especially the Deep South, continued to exist in economic depravity, and the recent Panic of 1873 only made conditions worse. The only states to experience much revival included the rapidly expanding states of Florida and Texas. The former grew due to continued carpetbagger settlement, and the latter grew due to an influx of Southern emigrates and massive railroad expansion along the frontier. Beginning during this period, the South experienced total economic isolation from the rest of the Empire, leading to the creation of a unique Anglo-based ethnicity only seen below the Mason Dixon Line.

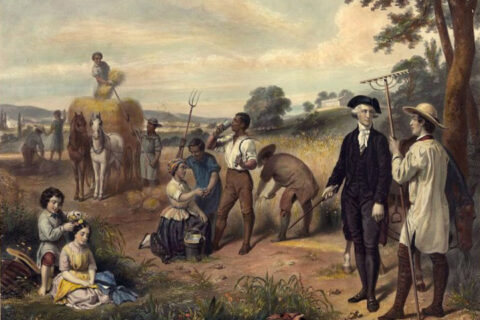

Southerners, both white and black, primarily sharecropped, tenant farmed, or worked a low end job in what few cities or towns existed, though many founded cities during this time. Sharecroppers and tenant farmers particularly faced hardship due to the lack of sufficient wages and often remained indebted to their employers, continuing the cycle of poverty. Generally, the South spent much of its time rebuilding from 17 long years of war and occupation. By 1890, the second phase of the Mississippi Plan took effect once Mississippi adopted its Constitution of 1890, a move which swept the rest of the Southern governments and finalized Jim Crow’s place within Southern society. Additionally during the 1890’s, various commemorative and fraternal groups which honored the Confederacy’s memory established as staunch purveyors of the Lost Cause’s memory, most notably the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. These events set the stage for that which came later in the Progressive Era.

The early Progressive Era, stemming from the late Gilded Age and its political machinations, experienced strengthening of Jim Crow Laws and revival of the Lost Cause among the Southern populace. Southern politicians continued to act as a powerful bloc within politics and governed their respective states with little to no issue from the federal government. Keeping in tandem with disfavor of universal suffrage among the populace and political class and the desire to preserve restricted voting, Dixie constituted the primary opposition to both the 17th and 19th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Culturally, the South experienced continued strengthening of Jim Crow Laws and also erected a great majority of its notorious Confederate Monuments. The Lost Cause experienced another revival during the 1910’s due to the mortality of the remaining Confederate Veterans, akin to the one it experienced in the 1890’s. In correlation with the Lost Cause’s revival, the Dunning School came into existence during the time and revolutionized the way society recorded history. The loathing Southerners held for the North and much of the Empire in general continued to grow since its revival in the 1890’s as well, producing the Greatest Generation and influencing the Lost Generation to embrace firebrand political strategies later during the 1930’s.

Economically, the Progressive Era granted little to Southerners’ benefit. The South continued in destitution, especially within the Deep South, and only a limited number of areas in the region experienced much growth. Texas, Florida, and Virginia generally fared better than most areas due to their larger cities and populations, but Georgia also received a modicum of economic prosperity within Atlanta and its surrounding metropolitan hubs. However, any scintilla of financial prosperity totally evaporated upon the onset of the calamitous Great Depression.

The Great Depression and World War II marked a notable shift in the overton window, a turning point in Southern politics, and a welcome form of economic relief. Southern politicians experienced a divide amidst themselves over Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Generally, they supported it just enough to continue their unmitigated sovereignty within their respective states but withheld from supporting many elements of populism or unionization the New Deal supported. They rightfully believed unionization to ultimately lead to the development of Communist entrenchment, as had happened in the industrial North and the coal mines of Appalachia. In contrast to the more conservative leanings of the Southern Statesmen of the time, Huey Long of Louisiana opposed the New Deal from a more populist left-wing angle, believing justifiably the New Deal was a scam which only gave the people a few crumbs when in reality promising a full meal. FDR also notoriously displaced Appalachians from their land and discriminated heavily the Cajuns and French Culture within southern Louisiana in addition to his heinous neglect of Southerners, a people he promised much to only to forsake them once he was ensured their vote. Generally, his most praiseworthy qualities were his commissioning of a study to determine the poverty of Dixie, the first president to do so and his lifting of discriminatory freight rates as well as a number of other sectional economic policies which hindered the South.

Culture and society developed more thoroughly during this time. A revival in stellar Southern literature grew rapidly. Movements such as the Southern Renaissance, most notable for the Southern Agrarians, an uptick in Southern Gothic, and various authors such as William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor graced American literature with some of its finest work. Jim Crow’s dominance remained unchallenged, but FDR only slightly genuflected to the desire of Negroes while the Southern men served during the War, the first time Southerners participated largely within one of the Empire’s conflicts since the War Between the States.

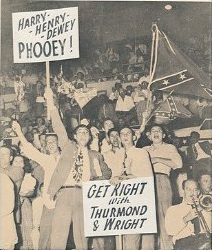

Derived from the aftermath of the Second World War, the Civil Rights Era began under the Truman Administration, and the era additionally produced the greatest era of Southern Statesmen. Turning against the Jim Crow system he came of age under, Truman endorsed and empowered the leftist Northern propaganda flowing at the time, attacking Southerners relentlessly. A number of Southern politicians angrily stormed out of the Democratic National Convention in 1948 in protest against Truman. Subsequently, these Southerners and a number of others established the States’ Rights Democratic Party in 1948 in opposition against the embedded leftism within the Democrats and the tyrannical, rapid expansion the federal government experienced during the Great Depression, World War II, and the Truman Administration.

The Dixiecrat Party, as it came to be called, marked the beginning of the end of the Solid South. Nominating James Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as its presidential candidate and Fielding Lewis Wright of Mississippi as his vice president, the party found most of its success within the Deep South. Putting up a hard fought campaign, the Dixiecrats attempted to create a contingent election, allowing for negotiations with the Republicans and Democrats. Their bid failed in its mission, and contrary to the urging from men like Leander Perez of Louisiana to keep the party around and build it, States’ Rights Democrats grudgingly moved back into more popular parties in misguided hopes to effect more influence within those parties. Though the Dixiecrats failed, they broke the stranglehold the Democratic Party held on the South and disintegrated the Solid South as a voting bloc of the liberalizing Democrats. This and the later signage of the Southern Manifesto in 1956 in opposition to the Brown v Board of Education ruling marked the final attempts for true Southern Nationalism to exert itself within the federal political sphere.

As the Civil Rights era continued to develop, the South slowly moved towards the Republican Party; however, this phenomenon did not take place instantly. Southerners lacked the willingness to go down without a fight but also continually grew suspicious of the Democratic Party. The dissolution of the Solid South began in the 1950’s when states like Texas and its pro-segregation, conservative governor Allen Shivers broke party loyalty to endorse Truman. A few years later, several Southern congressmen signed the Southern Manifesto in protest against the Brown v Board of Education ruling. Various forms of violence and political resistance took shape during the time, and multiple Southern governors defied attempts at legislation. Additionally, voting patterns remained chaotic and non-partisan during presidential elections as Southerners nothing to fill the void left by their expedition from the Democratic Party, leading to support of Barry Goldwater and George Wallace within the Deep South in 1964 and 1968 respectively and various sporadic electoral votes cast in favor of Republican presidential candidates during a number of elections.

A final attempt was made, via the guise of American Patriotism, for Southerners to assert their will within the political sphere through the political aspirations of Alabama’s George Wallace. Moderating his staunch segregationist views, Wallace achieved widespread appeal during the presidential election of 1972 and may have very well secured the Democratic nomination. However, the American Political machine resisted him, sabotaging his election by having him shot, confining him to a wheel chair for the rest of his life, and ending his political career. Dixie has since failed to continue asserting itself as a unified political bloc and prefers to attach itself to the whims of non-Southern hostile entities as opposed to seeking the enactment of its own will within the Empire.

The early parts of this period bestowed upon Dixie a wealth and socio-cultural stance not seen since antebellum society. However, the federal government’s betrayal of its part of the Compromise of 1877 ensured the worst for Southern society. Vehemently pushing Civil Rights and integration to the point of bayonet, Dixians experienced a wave of violence and antagonistic propaganda not seen since Reconstruction. Southerners increasingly responded to these transgressions and the government’s betrayal with malicious violence, as generally expected of those wronged by others. Unfortunately, the media continued to utilized these reactions to the detriment of Dixie, and the inevitability of the Civil Rights Movement’s ambition became more apparent. Following the Supreme Court decision of Loving v Virginia, the passages of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and the unconstitutional Fair Housing Act of 1968, and the repeated use of illegal military violence against Southerners, many lost faith. By 1970, the South’s public areas had totally integrated, their multi-generational struggle an unequivocal failure. From that moment, Southerners began reforming their identity to correlate more with the American identity as opposed to their own, crippling their ability to assert their influence within the political sphere.

To that end, the 91 year reign of the great Jim Crow Era finally came to a close. Growing in strength during the Gilded Age and reaching its legislative pinnacle during the Progressive Era while remaining unchallenged until the Truman Administration, the Jim Crow Era produced the greatest political and cultural developments in Dixie’s history, including the preservation of a unique Anglo-Celtic ethnicity. A tragedy in its conclusion, Jim Crow allowed for the development and preservation of America’s true founding stock and the hierarchical society it created. Unfortunately, the period remains the most abhorred era in American history, viewed as the nadir of the reign of terror instituted by vitriolic Southerners embittered over their loss of the War Between the States and the destruction of their wealth generated through slavery. On the contrary, Jim Crow produced Dixie’s greatest cultural achievements and deserves praiseworthy admiration from contemporary Southerners. Unfortunately, the malignancy of the contemporary leftist historiographic narrative ensures Southerners retain no memory of their preeminent moment within history, corrupting the memory of pride and grandeur to a false image of degeneracy and impenitent loathing.

“The White people of the South are the greatest minority in this nation. They deserve consideration and understanding instead of the persecution of twisted propaganda.” –Strom Thurmond

Nicely done, Sir. I don’t recall having read this when it was posted the first time, so I appreciate your reposting it for those of us who missed it the first time.

Also enjoyed listening in to the discussion of these topics on the latest episode of Rebel Yell, in spite of Rufus’s rude interruptions and fits of anger throughout the show. Ha, ha. Nah, I joke, I kid. I didn’t mind his angry little tirades at all. In fact I rather enjoyed them. Any Southerner worth his salt ought to be enraged by those things. That he is and occasionally “goes off” on them is perfectly understandable in my books. I do the same occasionally. My wife and kids probably wish I wouldn’t at times, but they’re going to get an occasional “ear full” whether they like it or not. That’s part of my job description, and none of them would ever try to deprive me of that even if the thought entered their minds. But from now on I think I’ll forewarn them of what is about to befall them by stating in no uncertain terms, “girt up thy loins like a man, I’m about to go all Rufus on ya!” LOL

I appreciate the complements. Yeah his tirades are fun to listen to.