The Redeemers represented the climax of the heroic struggle Southerners faced during the War Between the States and their struggles during Reconstruction. Often standing in the shadows of notable Confederates and the Great Statesmen of the 20th Century, the Redeemers played no small part in Southern history. Often being Confederate veterans themselves, the Redeemers brought Reconstruction, itself a war, to an effective end, at least temporarily, and saved their states from Radical Reconstruction, intermittently via means of bestial violence especially in the Deep South. The purpose of this essay is to examine the various Southern Bourbon Democrats who Redeemed the former Confederate States of America.

The Upper South

The Tarheel State, North Carolina, faced a chaotic Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction whilst recovering from the War relatively quickly. Characterizing the chaotic nature of Reconstruction and resistance, the state kept in vogue with many of its Southern contemporaries via aiding and abetting various paramilitary secret societies and, most notoriously, the Ku Klux Klan. The gubernatorial history of the state during the time is quite interesting. Governor Zebulon Baird Vance ran on the Conservative Party ticket, a moderate wing of the Democrats, and won during 1862 and served until the end of the War. William Holden won the governorship on the National Union ticket, an anti-Radical wing of the Republicans, and served during 1865 just for the governorship to be won again by a Conservative, Jonathan Worth, in 1865 who served until 1868. Holden was reelected in 1868 at the outset of Congressional Reconstruction and served until 1871. Vance would again be reelected in 1876.

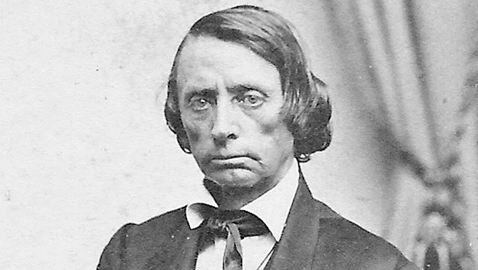

Redeemer Zebulon Baird Vance held a quaint, yet atypical, political career. Though many former Whigs filled the ranks of both Democrats and Republicans and served in the Confederate military, with a few becoming Redeemers, very few notable ones continued to switch parties or held much political office during the War as governors only to later Redeem their states. Additionally, Whigs were already a minority as Redeemers and in the makeup of the Democrats. Having moved from the Whig Party to the North Carolina Conservative Party during the War to the Democratic Party after the War, Vance endorsed the New South ideals of the era. The state recovered from the War quickly, relative to much of the rest of the South, but the brunt of that recovery took place after Reconstruction largely at the hands of men like Vance who supported the New South idea. The New South supported growth of the manufacturing sectors and sought to replace the old agrarian society with a more industrialized one, albeit with a continued racial hierarchy. Though North Carolina experienced a common history of Jim Crow with the rest of the South, Vance’s legacy solidified itself within the machinations of the New South movement.

Arkansas represented a bizarre case among the rest of the former Confederate States. Overlapping heavily, both regionally and culturally, with the Lower South region, the state still resides primarily within Appalachia and only seceded after Lincoln’s call for troops. Additionally, in regards to its placement along the Mississippi River, the state only had a slave population roughly one quarter the size of the total population and had the smallest overall population in the Confederacy. Moreover, Arkansas voted the most staunchly Democratic of all Upper South states.

During Reconstruction, the state initially refused to ratify the 14th amendment, much like the rest of the South; however, the state did refrain early on from passing draconian Black Codes and a harsh constitution. The general moderate stances of the state achieved little in abating the Radicals, and Powell Clayton assumed gubernatorial power in 1868. Powell viewed Reconstruction as a continuation of the war, a stance he was correct in believing, and set about crushing the “Rebel” Democrats in any applicable scenario he faced. Declaring martial law on multiple occasions, Powell’s militias engaged heavily against the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan maintained a powerful presence in the state due to its placement within Appalachia; nevertheless, the group maintained a minimal presence in the heavily Unionist northwestern section of the state. Another notable byproduct of the chaos and even the division amongst Republicans was the conflict known as the Brooks-Baxter War. In the end, the state succeeded in electing Democrat Augustus Hill Garland as governor in 1874 and brought an end to Reconstruction.

Garland, much like Vance, developed a unique political career by moving from one political party to the next. Beginning as a Whig and supporting the party until its collapse, he moved to the Know Nothing Party in 1855 and finally voted for the Constitutional Union Party in 1860. His record being a testament to his pro-American albeit eclectic and even right-wing political philosophy, Garland finally settled into the Democratic Party by the War’s end. His early tenure involved quelling the few remaining paramilitary forces and dealing with the aftermath of the Klan. He worked diligently to improve the economic standing of the state and to ameliorate the educational standing of the Arkansas. He presided over a surprisingly unexceptional governorship for being a politician with an atypical political history.

Radicals took control of Tennessee’s gubernatorial seat immediately at the close of the War Between the States. The state provided one of the premier battlegrounds during the War, having the second highest number of battles fought on its soil and provided the largest number of troops to the Union in comparison to the other Southern States. The state also remained the most moderate on the secession issue and was the second to last state to join the Confederacy; the pockets of Unionism resided in East Tennessee as opposed to the secessionist factions in West Tennessee and Middle Tennessee being moderate on the topic. The wilted population due to casualties, inherent opposition to the War, separation from the brunt of the Negro population, disfranchisement of Confederates and isolation of the Appalachian terrain allowed the population to easily bend the knee to Radical control.

Despite its willingness to cater to the Republican government, the state produced a great deal of resistance, birthing the infamous Ku Klux Klan as a reaction against Governor William Brownlow. Brownlow’s Republican successor Dewitt Senter, directly contributed to the Redemption of the state. Senter, supporting the Radicals initially, succeeded Brownlow in 1869, focusing his tenure on combating the Ku Klux Klan and rolling back some of the divisive Radical legislature. One of these was granting former Confederates the right to vote, effectively giving the 1870 gubernatorial election to Democrat and Confederate Officer John Calvin Brown. Brown, a Bourbon Democrat, governed a moderate tenure and focused on paying off the state’s war debt as well as fiscal responsibility. Additionally, he worked to better organize the public school system in the state, establishing seats for city and county superintendents, as well as, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction. This also included allowing the state legislature to levy small taxes to fund the school system. Though more moderate than many of his Democrat contemporaries, he did advocate for a segregated schools system. Generally speaking, Tennessee’s Redemption came earlier than several other states and ended without much violence and the polls.

Virginia, the birthplace of America and primary focal point of the Confederacy, fared better than most of the rest of Dixie during Reconstruction, keeping in trend with the rest of the Upper South. That being stated, The Old Dominion laid in deep ruin following the war, as it was the primary battleground of the War. The state remained mostly untouched by the uncontrollable violence which engulfed the rest of its Southern cohorts. In contrast, Virginia was readmitted to the Union a bit later in 1870, as opposed to most of the rest of Dixie which were readmitted in 1868. Virginia’s cities rebuilt quickly, and the state was the only state of the former Confederacy to elect a civilian government following the passage of the Reconstruction Acts which did not become more Radical, and the election took place non-violently.

Detailing the State’s Redeemer proves a difficult task. The first Democratic governor to assume office during Reconstruction was Gilbert Carlton Walker who had previously been a Republican upon his first win in 1869. He migrated to the Democratic Party the following year during the next election. Both of his tenure were relatively uneventful. The next governor, James Kemper, was a Democrat during his tenure which began in 1874 and lasted until 1878.

Kemper was a staunch moderate. He worked to bring fiscal responsibility to the state, and he feuded heavily with the Funder Party over the methods of paying off Virginia’s war debt. Kemper’s racial attitudes proved so benevolent he drew ire from various other moderate former Confederates, the most notable of these came from Jubal Early and his criticism that Kemper allowed a Negro militia group to attend the commemoration of a statue in Stonewall Jackson’s honor. Overall, he presided ove a good governor’s tenure but tended to disagree and even oppose many of the sentiments of his former Confederate contemporaries.

The Deep South

Moving further down into the Deep South, Florida, a strange and eclectic state during the entirety of its history, experienced Reconstruction not in a particularly violent way but still managed to be one of the last states readmitted to the Union. Immediately following the War, the state elected Democrat and former Constitutional Unionist David Walker as governor. Like every other governor of the time, he was replaced by a Radical by 1868. The state went through a few Republicans until finally being landed with Marcellus Lovejoy Steams in 1874, a Union Army veteran from Maine. Though the information certainly exists, thanks to the actions of few students of history such as the Dunning School, the history of the time proves difficult to research and a bit vague.

As a result of following the Mississippi Plan in 1876, George Franklin Drew assumed the governorship in 1877 as a Democrat. The late redemption of the state can be attributed to the lack of militancy and thinly dispersed, small native cracker population, as well as, carpetbaggery and large Negro population. Drew’s tenure remained heavily uneventful other than a series of typical Democratic legislative actions at the time with much more noteworthy governorships succeeding his own such as William Bloxham and Edward Perry. Many of the truest aspects of Redemption did not grace the state until the 1880’s. Florida would continue to elect Democratic governors until 1967.

Unlike most other states to comprise the Deep South, Georgia achieved Democratic control early in the 1870’s with little resistance from Republicans upon the election of its Redeemer Governor. That fact being stated, Georgia faced considerable Radicalism and violence during Reconstruction. Georgia historically maintains a moderate political record and did even back then. Though its electoral votes went to John C. Breckenridge during the Presidential Election of 1860, the northern half of the state voted heavily for John Bell. The state even refrained a bit from immediately enacting Black Codes after the War. Much of the reasoning behind this attributes to the fact many Scots-Irish live in the northern part of the state, and the more moderate, culturally not Southern cities, most notably Atlanta, reside in the region.Though moderate, Georgia was one of only two former Confederate states to vote against Ulysses Grant in the 1870 Presidential Election.

Nonetheless, James Milton Smith win the Election of 1871 and redeemed the Peach State. His election came after a few years of intense violence during the late 1860’s and 1870. During that time, Georgians ousted various Negro politicians from the state senate and lower house, as well as, various campaigns of violence. The Ku Klux Klan became so notorious for its many acts of terrorism the state became a primary target of anti-Klan legislation. Amos Akerman, a former Confederate turned scalawag, notably campaigned against the Klan in the state. Smith’s ascension put an effective end to much of the violence. A relatively uneventful gubernatorial tenure, he is most memorable for his successful work in rebuilding Georgia’s economy and relieving its state debt, in addition to restoring the state’s credit rating. He left office in 1877.

Alabama remained relatively unremarkable during Reconstruction. The state faced a fairly typical, albeit harsh, Reconstruction period. Alabama’s gubernatorial history was a bit strange even during the War. Much like Georgia, the northern populace provided a substantial amount of support for Unionism pre-secession and split the vote; however, they failed to prevent secession. Regardless, Alabamans served valiantly for the Confederate Cause. Interestingly, during the War, a Whig by the name of Thomas Watts won as governor in 1863. Additionally, Alabama was also the only state in the Lower South to elect a Whig, as opposed to a Democrat, during Presidential Reconstruction in the initial years after the War. This Whig was Robert Patton and served from 1865 to 1868. Though Radical Reconstruction asserted Republican rule, Alabamans managed to elect a Democrat, Robert Lindsay, in 1870 who served until 1872. Democratic control did not finally dominate the state until the Election of 1874.

George Houston, the Democrat winner of the election, served as a Bourbon Democrat. Not the most noteworthy of Redeemers, Houston genuinely worked to reform and rebuild his state; however, he generally found difficulty making progress in his endeavors due to preexisting conditions. His tenure involved the establishment of some of the very first public health boards in the country, promotion of immigration into the state with little success, expansion of the state’s contract lease system, and support for a constitutional convention. Another aspect of his tenure involved his attempt to reform the public education system, but he ran into conflict with state debt based on inherited railroad bonds. Alabama continued to produce Democratic governors until 1986.

Texas, after experiencing harsh rule under Governor Davis, managed to elect, via a mass movement joining moderates with secessionists, Richard Coke to the governorship of the Lone Star State. He became the first in a long line of excellent, noteworthy governors of the state, the most noteworthy being Lawrence Sullivan Ross and Robert Allan Shivers. The state, under Davis’ leadership, experienced abuse at the hands of the state police and state militia, both of which heavily enlisted Negro males, in addition to total disfranchisement of former Confederates and widespread lawlessness. The surprisingly peaceful but zealous movement to remove Davis resulted in Confederate veteran Richard Coke winning the Gubernatorial Election of 1873 and assuming the Governor’s chair in 1874.

Davis refused to concede defeat and did not leave the state capitol, forcing Texans to climb the building and storm it from the roof and windows. Governor Coke presided over a tenure which worked diligently to balance the state’s budget and revise the state’s constitution, adopting a new constitution in 1876. Additionally, he worked in conjunction with others to establish the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas which later became Texas A&M University. Coke also appointed every member of the Texas Supreme Court and appointed various former Confederates to important positions. Following the finalized drafting of the new state constitution, Coke resigned from the governor’s office to take up a newly won seat in the United States Senate. Texas, after a harsh Reconstruction, was the second of the “Original Seven” to achieve Redemption.

Arguably the state to face the harshest Reconstruction and deserving of an entire essay of its own, Louisiana fought bitterly against its conquerors. The state, especially the city of New Orleans, represented a grand prize for the Union Radicals. The protectionist sugar Planters and the power of Whigs within the city as well as the state’s large previously free Negro population convinced Northerners the Crescent City provided the foundation for a Republican stronghold. Contrary to their initial beliefs, New Orleanians proved maliciously adversarial to Federal occupation and later Reconstruction. Throughout the period, New Orleans, and the state overall, experienced the most sanguinary acts of brutality the South experienced during Reconstruction. Race riots took place constantly across the state even during Presidential Reconstruction, and the Knights of the White Camellia worked alongside various groups in New Orleans to enact various campaigns of terror across the state, a role which the White League would later fill after the Panic of 1873. Louisiana experienced a Reconstruction in which all manner of restraint was removed from the Radicals at the behest of the Reconstruction Acts and the Grant administration, leading to much of the brutish, anarchic violence which consumed the state.

After a long period of horrid governors, constant voter fraud, and the removal of two elected Democratic governors, Louisiana managed, adopting its own form of the Mississippi Plan, to elect Confederate veteran Francis Nicholls to the governorship in the infamous Gubernatorial Election of 1876. He was inaugurated in 1877 only after President Rutherford Hayes allowed the Compromise of 1877 and recognized his legitimacy in the disputed election. He combated political corruption, a long Louisiana political tradition, during his first term and opposed the lottery. He also presided over the state constitutional convention of 1879, and his term ended in 1880. Nicholls would later be reelected to governor in 1888 and served until 1892. The second tenure also gained him negative public attention due to his refusal to prevent 11 Italians from being lynched in 1891. His tenure brought an end, and an element of stability, to arguably Louisiana’s darkest period.

Spearheading the secession movement of 1860, South Carolina, the birthplace of the Deep South and the first state to secede, experienced a notably intemperate Reconstruction, much like Louisiana and Mississippi. One of the earlier states to enact Black Codes, The Palmetto State received much of the initial brunt of intense Radical Reconstruction. Though blessed with a moderate Democrat during Presidential Reconstruction, the state, much like the other states in the Deep South, endured austere Reconstruction beginning in 1868, already being a major target for aforementioned Black Codes as well as having spearheaded the secession movement. Enduring deep political corruption and stark fall from glory, South Carolina adopted the Mississippi Plan in 1876. Adopting the Red Shirts from the Magnolia State as well as employing various militant rifle clubs, the Gubernatorial Election of 1876 was rife with political violence and intimidation. Various riots and massacres sparked mass media and political outrage in the North, particularly the Hamburg Massacre. Even after the election, the Radicals refused to concede to defeat and set up a parallel government to the newly elected Democratic government. Ultimately, the state was successful in electing the Confederate veteran Wade Hampton III to the governorship following a ruling by the South Carolina Supreme Court, making South Carolina the last state to achieve Redemption.

Hampton, a staunch proponent of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, accrued the nickname “Savior of South Carolina.” More moderate than his Red Shirt and militant supporters, which he owed to his electoral victory, he generally presided over a temperate tenure. Serving as governor from 1876 to 1879, Hampton resigned and served as a senator in the U.S. Senate from 1879 to 1891. He set a precedent for having redeemed one of leading states of the Deep South as well as its continuation of the violence sparked by the Mississippi Plan. Additionally, he set the standard for what essentially culminated in a long line of pristine governors to rule South Carolina and the adoption of the South Carolina Constitution of 1895.

Last, but certainly not least, the great Magnolia State of Mississippi, through tribulations and turmoil, seated John Marshall Stone in the governor’s chair in the violent, uproarious Gubernatorial Election of 1875. The state faced arguably the harshest war crimes at the behest of the Union Army during the War Between the States, and the western parts of the state had to endure such conditions for much of the War. Mississippi fell into deep economic degradation as a result of the War and its reliance on the Cotton Economy, with the last vestiges of hope for a return to economic prosperity ending following the Panic of 1873.

Mississippians justifiably put significant capital behind removing their Radical oppressors from the governorship and public offices. After the end in 1871 of the various campaigns of terror wrought by the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camellia, followed by the period of relative peace between 1871 and 1873, Mississippians prepared for and organized the massive resistance seen during the Gubernatorial Election of 1875. Named the Mississippi Plan, the state experienced widespread violence in reaction against Radical Reconstruction under Governor Adelbert Ames, forming the paramilitary organization the Red Shirts as a means of orderly resistance. Various riots, massacres, intimidation of Negro and Radical voters, and political alliances plagued the election, resulting in the ousting of Ames and placement of Confederate veteran John Marshall Stone in the governor’s chair. The Mississippi Plan provided the blueprint for the successful Redemption of Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida in 1876.

Stone ushered in various early Jim Crow and segregation laws in the state and ensured staunch Democratic rule. As Governor of Mississippi, he served longer than any other Mississippi governor to date; additionally, he served two non-consecutive tenures. The first lasted from 1876 to 1882 and the second from 1890 to 1896. During his second tenure, the state ratified its new constitution which strengthened and established strict racial laws. This set another precedent for other Southern states to follow and a trend of legislative acts which lasted until 1908, solidifying Jim Crow rule in Dixie. Much like Texas and South Carolina, Mississippi continued to produce a line of outstanding governors well into the 20th century.

Each era of Dixian history generated its own heroes, Reconstruction being no exception. The Redeemers established their legacies via saving the South from Radical Reconstruction, ushering in the beginnings of Dixie’s golden age, as well as, laying the foundation for the later solidification of the Jim Crow Era and segregation during the 1890’s and early 1900’s, and 8 of the 11 Redeemers also carried the additional quality of being Confederate veterans, the deviations being Alabama, Florida, and Arkansas.

Contemporary, neo-abolitionist historians wish to remove these individuals from history, leaving a few remaining traces to assert the narrative commonly utilized to demean Southerners and their history. Redeemers once garnered the title of heroes, but they now only vaguely receive mention in history to personify the supposed atrocities Negroes and Radicals faced. Only with time may they be remembered for shepherding Dixie out of that direful time, delivered from the status as Southern villains relegated to the forgotten dustbin of history.

“The White people of the South are the greatest minority in this nation. They deserve consideration and understanding instead of the persecution of twisted propaganda.” –Strom Thurmond

A key point was missed as to why so many Radicals were elected in the first place at the beginning of Reconstruction, and why out of necessity the Klan was formed.

The focus here was on the Redeemers.

But yes that is an important part of the story