Author's Preface: It has been a hot minute since the last entry into the Great Statesmen series. The book I used to write this is inordinately dense, even for a biography, and I unfortunately was forced to heavily summarize and water down the various topics discussed in that book. It will be cited in the bibliography at the end of the essay, and I do encourage you to read it as it is an important preservation of an interesting figure in Louisiana's political history. While the author was a condescending liberal 20th century historian, he was surprisingly unbiased in presenting the facts. His bias bled through in the parts about race and were blatantly stated in the epilogue.

“Do you know what the Negro is? Animal right out of the jungle. Passion. Welfare. Easy life. That’s the Negro.”

–Leander Henry Perez Sr.

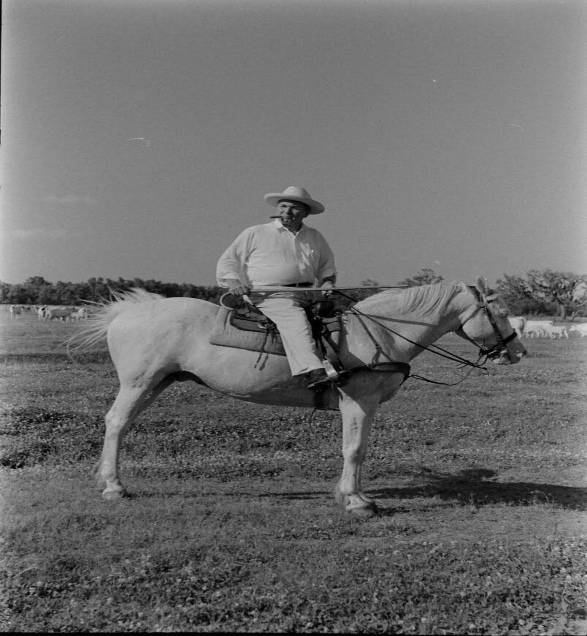

There exists, albeit scarcely nowadays, a small ethnic minority in the fetid bayous and parishes of southeastern Louisiana. Despite their lack of recognition, they once contributed greatly to the cultural and historic development of the Pelican State. While overshadowed by the more culturally significant and renowned Cajuns, these people were the Isleños. One of Louisiana’s most preeminent statesmen once belonged to this forgotten folk, of whom Plaquemines and St Bernard Parishes comprised, for a time, his fiefdom during his storied and tumultuous profession. The purpose of this essay is to shed light upon and detail this eccentric, boisterous man’s life and career.

The Isleños were Spanish colonists, mostly of Canary Island origin, to Louisiana who settled there during the Spanish Louisiana period of 1778 to 1783. Of this obscure demographic native to rural southeast Louisiana, there belonged a man named Leander Henry Perez, Sr. Born in Plaquemines Parish on July 16, 1891, he was raised in an isolated, rural area at the family home on Star plantation about 10 miles south of Belle Chasse, Louisiana. While an indigent and sparsely populated parish, the Perez’s a lived relatively comfortable lifestyle due to Roselius Perez’s, Leander’s father, ownership of two plantations which typically grew rice and sugarcane. The Perez’s were strict disciplinarians and devout Catholics who emphasized hard middle-class work ethic and education; however, they were also heavily family oriented and quite loving.

Though having attended some high school in New Orleans, Perez decided it was a waste of his time and dropped out, later enrolling in Louisiana State University. While there, he studied law and was quite active in extracurricular activities, playing the French horn in marching band, playing on the football team, and garnering a reputation as a bit of a ladies’ man. Upon graduation, he enrolled in Tulane University Law School. Known for being a determined striver and his assiduous nature, Leander’s personality strayed from this during his tenure at Tulane. His grades and participation there were best described as mediocre and average; however, despite this, he graduated from Tulane with a law degree in 1914.

Following his education, Perez opened his own law practice. Pitiful describes his early years as a lawyer well. For a while, Perez barely managed to scrape together a subsistence living off of it. His big break would not occur until December 1919. Robert Emmet Hingle, judge of the 29th Judicial District which encompassed Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes at that time, unexpectedly died from drowning during a fishing accident. The incoming governor-elect, John M. Parker, who happened to be a progressive reformer, was designated by the outgoing governor Ruffin G. Pleasent to appoint a replacement for the remainder of Hingle’s term. A supporter of John Parker just so happened to be John R. Perez, a cousin of Leander. John Perez talked John Parker into giving the appointment to Leander. Needless to say, this did not go over well with the tight knit political machine at the time, who balked at the position being given to a young, unaccomplished aspirant without their consent. This began the war Leander ultimately fought against the political machine, known as the Old Regulars, in order to solidify his place in Louisiana’s political sphere and the beginning of his two-parish fiefdom.

Leander’s war against the Old Regular clique in 1920 became the first true political test of his willpower and mettle. He ran for district judge while his running mate, Phillip Livaudais, ran for district attorney. During this, he allied himself with a Democratic Party reform faction out of New Orleans called the New Regulars. Even at such an inexperienced and young age, Perez showed incredible lawfare finesse, stacking positions and a grand jury with his New Regular friends. Through the grand jury, he was able to impose indictments on his opponents. The heavily energetic campaign resulted in a disputed vote tally. It was ultimately decided that the Perez-Livaudais ticket succeeded; however, the Old Regulars succeeded in all other local election positions.

While this first major victory did allow Perez to begin stuffing his allies into numerous positions, he was not yet out of the woods. John Dymond was a formidable foe for the young judge within the ruling political machine and was determined to end Leander’s rise to the top. Their feud was lengthy and eventful, and the details of it could fill another essay altogether. In the end, it is important to note that by the end of 1924 the Old Regulars had been ousted from the 29th Judicial District, with Perez having also been elected to attorney general that same year, and Leander firmly grasped the reins of control, albeit with much of his St. Bernard power reliant upon his alliance with the parish sheriff.

Judge Perez’s next major venture arose as the Trapper’s War. Fur trapping exploded in the lower Delta during the 1920’s, largely as a result of industrialization and the excess lavishness of the era. As a result, parasitic land grabbers rapidly bought up vast swathes of land in the area and began charging local, mostly Isleño, trappers to hunt on the land which they had already been hunting on for generations. In 1924, they found their champion in Leander Perez who quickly established the St. Bernard Trappers’ Association and the Plaquemines Parish Protective Association. He would go on to use these organizations to buy up marshlands and lease them out to Isleño members of the organizations, while also keeping a gratuity for himself. While this proved satisfactory for a time, many Isleños grew irritated with some of the absurd lease prices which the associations levied at them. This grew into a number of legal battles, lawfare, and violence, with tensions rising so high that they climaxed in a shootout on Delacroix Island between some Isleños and Perez’s hired guns which resulted in one man being killed. The tensions later fizzled following the shootout as the trappers returned home and police being unwilling to patrol the island. No legal action was taken and the Perez’s sold the land to Manual Molero, a representative of the Isleño trappers, in 1926, bringing the whole fiasco to an end.

Before continuing further, his reputation necessitates a brief discussion of how The Judge managed to accrue his exorbitant wealth. Power requires financial support. It all laid in the rich mineral wealth and oil deposits in the Delta swamplands. By the early 1930’s, much of the swamplands were owned by the state which, not having the foresight to understand just how much wealth existed within them, began the process of giving the lands over to the local levee boards. Seeing this, District Attorney Perez frantically created numerous ghost oil, land, and realty companies, often based all over the United States and never directly connected to his name, which then acted as the final step in the transfer of these lands, effectively buying up and monopolizing the leasing of the land. By far the largest and most considerable of these was the Delta Development Company; that particular company was believed to have obtained up to $80 million in oil royalties. From that point, no oil companies or other businesses seeking to extract the natural resources in the area could avoid leasing it from one of the multitude of organizations Perez secretly owned. It has never been discovered just how much money he accrued over the years until his death, and he never directly addressed or answered inquiries into the matter, a testament of his craftiness. Following his death, the parish sued his descendants for $82 million, but it only received $12 million in a settlement outside of court in 1987. It is worth noting that despite his excess wealth he never lived lavishly and ostentatiously, utilizing most of his money to allow him to spend most of his time dedicating himself to the world of politics.

Following the end of the Trappers’ War, Perez turned his gaze to a firebrand upstart from Winnfield, LA. A populist Baptist from the impoverished Winn Parish in North Louisiana, Huey Pierce Long Jr. was a man deserving an entire essay of his own. Blessed with an uncanny ability to recruit powerful and talented men to his camp, he won over men such as US Senator Allen Ellender in 1928, a staunch enemy of Long’s during the latter’s 1927 gubernatorial campaign. Perez joined the Long faction during Long’s first year of his term.

The relationship between the two was symbiotic. Perez had access to state contracts and a direct hand in public appointments alongside the prestige of being close to the governor which allowed him to gain influence and a reputation outside his own bailiwick; whereas, Long gained friendly access to one of the best lawyers in the state and undeniable votes from two parishes. The two men also had strikingly similar personalities. Both men were ambitious tub-thumpers with authoritarian political approaches and indefatigable work ethic. They both also heavily supported public works programs. Both were considered insurmountably intelligent by their peers. However, they ideologically differed just as much. Long was a liberal populist Baptist while Perez was a right-wing reactionary Catholic. Long championed to poor man while Perez favored the company of ultraconservative millionaires. Long was a bit too left-wing in his Share the Wealth Program for the Judge’s comfort and sought to achieve the Presidency of the United States someday; contrarily, Perez preferred local and state politics. Despite the differences, Leander never openly criticized Long for anything the former considered a fault and was one of his champions.

Governor Huey Long immediately gaining notoriety and opposition in the state capitol upon assuming the governorship is an understatement, thanks largely to his populist opposition to the ruling political machine. Specifically in 1929, Governor Long was attempting to push through a five-cent per barrel tax on refined oil production to fund his plethora of social programs. The Louisiana State Legislature, largely owned by big oil companies, balked at this proposal, and they decided to impeach Long. The legislature produced a list of trumped-up impeachable offenses which included charges of blasphemy, subornation of murder, nepotism, and corruption. Huey quickly ended the session out of concern which only fueled his opponents’ furor even further which then sent the governor into a panic. He holed up in his hotel room afterward. Seizing the opportunity, Perez rushed to the state capital to offer his assistance. To keep it brief, Long received some of the best legal defence in the state including Leander Perez, John Overton, and Allen Ellender. Ultimately, he was acquitted of all charges. His loyalists were handsomely rewarded with both Overton and Ellender going on to the US Senate. Perez was rewarded differently. He utilized his friendship to ensure more control over the levee boards that owned much of the mineral rich swamplands in Plaquemines; therefore, Leander was able to accrue a large amount of royalties and leases for himself and his parish. Always happy to reward his friends and allies, he secured Plaquemines and St. Bernard for Huey Long’s successful US Senatorial campaign in 1930 and remained a supporter until Huey’s suspicious assassination in 1935.

Though the death of Huey Long did not serve Perez well, the death of Leander’s vital St. Bernard ally, Sheriff Meraux, began the end of the Judge’s period of tranquil quietude and unchallenged, comfortable power in lower Delta politics. Sheriff Meraux’s brother, district judge J. Claude Meraux, split with Perez over an appointment to a recently opened position on a levee board. Sheriff Dutch Rowley, the previous sheriff’s successor, initially remained neutral but ultimately sided with Meraux. This quickly erupted into a large local political dispute, with all the malicious mudslinging once common to Southern elections, in which Governor Sam Jones eventually got involved and a bitter Democratic primary election for local offices had Perez attempting to unseat Sheriff Rowley in 1940; of course, Perez’s pick for sheriff, Manuel Molero, failed to win election. A number of lawsuits occurred in which Perez successfully had Meraux removed from office. Perez again unsuccessfully attempted to defeat Rowley in 1944. Furthermore, Rowley and Perez both supported opposing candidates for the 1944 gubernatorial elections. Eventually by 1948, Leander Perez reconciled and buried the hatchet with both Meraux and Rowley, ironically becoming a political ally and supporter of Rowley’s. Unfortunately for the Judge, this baleful feud took place concurrently with another fight he found himself in with the aforementioned governor.

Sam Jones, an anti-Longist, defeated Earl Long, Huey’s brother, in the 1940 gubernatorial election. Initially quarreling over an attempt to do away with the 2% sales tax passed as part of the Long reforms, Governor Jones really gave Perez a run for his money when the former created the Louisiana Crime Commission. Its purpose was to recover state funds that had been diverted via deception and fraud. It also had subpoena power which granted it considerable investigative power. Predictably, the commission immediately went after Perez. After a series of high-octane legal battles, the state supreme court sided with Perez and abolished the commission. Jones then attempted to break Perez’s financial empire by appointing a number of people to the St. Bernard and Plaquemines levee boards in an attempt to have them remove Perez as legal advisor to the boards; this ultimately failed due to local parish court rulings.

The bombastic legal battles previously mentioned entertained Louisianans and made for good news stories; however, the clamorous and grandiloquent climax of the feud occurred in what is known as the Little War of 1943. The fuse was lit when Plaquemines Sheriff Louis Dauterive unexpectedly died while in office on June 1, 1943. An interim sheriff needed appointed to finish his term. Typically, the governor would appoint the sheriff, but Perez found a legal loophole in the state constitution itself, which stated that the parish coroner would assume the legal duties of parish sheriff until the end of the term. Jones chose a man named Walter Blaize, and Perez supported Plaquemines coroner Dr. Ben Slater. The situation quickly escalated to the extent that Slater deputized an entire militia in Plaquemines, the courthouse at Pointe a la Hache was barricaded, and roads into the parish were blocked, making it impossible for Blaize to be sworn in. Meanwhile, Governor Jones declared martial law in Plaquemines, activated the Louisiana National Guard, and ordered them to invade the wayward parish. Though sabotaged and slowed along the way, the Guard ultimately took over the parish. Nobody was killed as the entire event was a display of force and a test of willpower between the Governor and the Boss of the Delta. Perez did quietly leave the courthouse just before the Guard subdued it, and he could then be seen at either New Orleans or under armed guard at his home in Dalcour. Local sabotage and hostile disposition made the job nearly impossible for Blaize as Slater operated his own rival sheriff’s office with the backing of the natives; although, the latter was eventually removed by the Guard. As soon as the opportunity presented itself, Perez filed a library’s worth of lawsuits against the governor. Jones responded with a slew of his own suits and attempted to impeach the rebellious district attorney and his district judge ally, Albert Estiponal, Jr. Estiponal’s temporary replacement, Judge R. R. Reeves presented the case to the state supreme court which rejected it. Reeves ultimately ruled in favor of Perez and concluded on April 4, 1944, that the Governor’s declaration of martial law was unconstitutional. Subsequently, the governor pulled the last Guardsmen from Plaquemines on May 4, 1944. Jones’ term ended five days later. Jimmie Davis, a country music and gospel singer, succeeded him, and Perez became an ally of the new governor. Sam Jones, if given the time but unable to succeed himself as governor or if his successor had been of his camp, possibly could have broken the Judge’s power. However, this was not meant to be and quiet peace returned to the Delta.

Following his war with Governor Jones, Perez faced no serious threat within his dominion until the 1950’s. Although an avid supporter and friend of Huey, Perez eventually developed a notably bitter and malicious feud with Earl. While initially an ally, Earl Long’s moderate views and adherence to national party politics soured his relationship with the previously confederate Judge. Specifically, the seeds of this feud took root in 1948 quickly after Long assumed the governorship. He refused to back the Thurmond and Wright ticket for the States’ Rights Democratic Party, or Dixiecrat Party, of the same year. Not long after during the meeting of the Democratic State Central Committee, Long ousted Perez ally W. H. Talbot from the committee for supporting the Dixiecrat vote. However, the straw that broke the camel’s back was Earl Long’s reneging on commitments and deals he made with Perez. By 1950, they were enemies. A friend of Leander’s claimed that upon his falling out with the governor the Judge rushed to the governor’s mansion, stuck his finger in Earl’s face, and said, “I’ll break you.” By the time the dust had settled, the prophetic statement proved true.

This ultimately culminated in a political war in which Long did his dead level best to destroy Perez’s career and break his fiefdom in Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parishes. From 1950 to 1952, Long pursued consolidation of more power into his hands, largely in an attempt to strengthen his grip over levee board appointments and leasing of mineral deposits, and heavy taxes, which decreased his popularity. Despite the popular setbacks, he and Perez did duke it out over who would be the succeeding governor. Perez’s pick, John Kennon, defeated Long’s pick, Carlos Spaht. However, the anarchic fortunes which defined Perez’s control of St Bernard Parish turned against him once again in 1953 when Sheriff Rowley passed away and was replaced with a more independently minded Nicholas Trist who soon found himself a target of The Judge. This and Earl Long’s success in the 1956 gubernatorial election placed Leander in a precarious scenario.

Earl Long, in his final term as governor, posed the single greatest threat to Perez’s power that the latter faced in his lifetime. Bellicose and grudge-bearing, Governor Long wasted no time in combatting Perez’s power the moment he smelled blood in the water. The “blood” was the fracturing of The Judge’s supporters in St Bernard upon finding out that Perez had secretly been mending relations with Sheriff Trist. These newly minted opponents formed what was called the Third Party. Long, quickly allying himself with the disgruntled faction, introduced and pushed through the legislature a package of eleven bills which gave him the power to directly install the Plaquemines boards, reform the levee district boundaries, and alter the authority of the levee boards. The vanguard bill at the tip of the spear in this legislative armory allowed the governor to appoint twelve additional members to the police jury, the governmental structure which administered St. Bernard and Plaquemines at the time, which considered levee board affairs, being dubbed the “piggyback juror law.” Always exigent and crafty, the Judge immediately brought the piggyback law before the courts, taking it all the way to the Louisiana Supreme Court and kept it tied up until the end of Earl’s term.

There were other battles. Earl Long’s large tax program was halted and killed by Perez in the state legislature. Ironically, this sort of bill was reminiscent of something Huey would have introduced, but Leander was quite rancorous and spiteful with Earl. In another instance, Perez attempted to have the courts audit the St. Bernard police jury which, at that point, had multiple Third party and Long allies. During their various debates in the legislature over the years, in one instance, Long and Perez became so vehemently irate with each other that onlookers believed them about to come to physical blows, both men having been known in their younger years for fist fighting their political opponents.

By 1959, Governor Long’s health was in decline. He had a weak heart and was suffering a mental breakdown because of his campaign against Perez. The latter condition was so extreme that his wife had him admitted to a mental health institution from which he shortly escaped by filing a suit of separation against his wife and firing the hospital superintendent and having the superintendent’s replacement declare the governor mentally healthy. However, this hiccup as well as his moderating stances on racial integration, sorely damaging to his reputation, did not deter Long from attempting to unseat Perez’s allies in the elections of 1960. This was a landmark gubernatorial election as it had eleven candidates, was highly tempestuous, and was the first time since Reconstruction that race was the foremost issue. Deciding not to run for reelection as governor, Long chose to run as lieutenant governor and backed Jimmy Noe while Perez supported former governor Jimmie Davis. Long supported John Rowley for St Bernard sheriff while Perez backed Nicholas Trist. Ultimately, Jimmie Davis won the gubernatorial election, and Trist won the sheriff election. Additionally, 11 of 13 police jury seats were won by Perez allies in St Bernard. By 1961, St. Bernard and Plaquemines switched over to a commission form of government. This rambunctious political war marked the end of Earl Long’s career, and it was the single greatest threat Leander Perez faced. Following this, his gaze fixed upon another major issue which engulfed all of America.

From the outset of his political career, Perez adhered strictly to racialist views. Much of the foundation for the allegiances he chose to make resided in the given politician’s views of segregation. This explains his support and allying with statesmen such as Jimmie Davis, Louisiana State Senator and Representative William Rainach, and Allen Elander. These beliefs and his loathing of Communists drove him towards national political affairs as the Civil Rights Revolution grew and consumed America, setting its sights on the Jim Crow South. That color revolution defined Perez’s career during the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Heavily involved in the Citizen’s Council of Greater New Orleans, Perez worked tirelessly to prevent Louisiana’s integration. He kept in touch with George Wallace of Alabama, WJ Simons and Tom P Brady of Mississippi, Jim Johnson and Orval Faubus of Arkansas, and Lester Maddox and Roy Harris of Georgia. Furthermore, he studiously researched Negroes and communism within the revolution of the time. Mocked during the time as conspiracy babble, communism was indeed heavily responsible for and deeply ingrained within the movement. While the efforts in New Orleans found little success, the Judge did all within his power to prevent integration in Plaquemines and made it one of the last places to integrate in the state, not fully doing so until 1967. He went so far in his fight against integration that he repurposed the old Fort St. Phillip as a prison to house demonstrators, many of whom were often outsiders and bleeding-heart Yankee do-gooders. However, White Louisianans in the parish, including teachers and students, boycotted schools which then went into decline as Perez prevented the funding of those institutions. By 1971, the Caucasians began returning to schools, and the Pelican State moved on from the Jim Crow era and battling integration. The North won another war against Dixie.

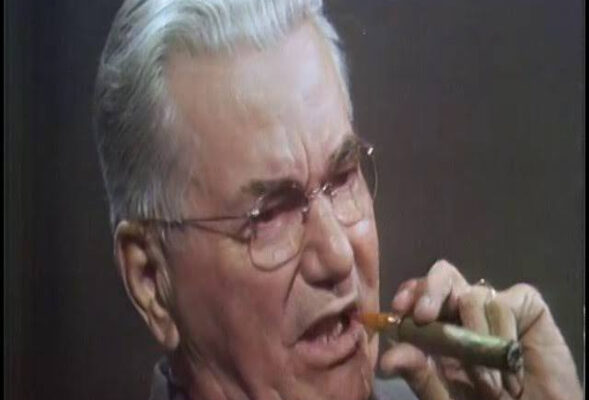

His final political hurrah and one of his greatest achievements in Louisiana politics was the Wallace Crusade. By 1960, Perez began waxing and waning and shifting at a moment’s notice the sort of men he supported in the presidential elections. He began in the Free Elector movement and pushed for Harry Byrd of Virginia in the 1960 election and later shifted to Barry Goldwater support in the 1964 presidential election. By 1965, he became an unwavering George Wallace supporter. Pulling out every trick and tactic up his sleeve, Perez did all he could to hand Louisiana to Wallace in the 1968 presidential election. From financing his campaign in the state to advertising to political machinations, Perez was all-in. At one point in 1968, Perez appeared as a guest on the actorly, flatulent William Buckley Jr.’s popular political talk show The Firing Line. Although not performing well enough to be a spoiler candidate as Wallace hoped due to his horrendous vice-presidential pick, Curtis Lemay, Louisiana voted for Wallace. This was the crown jewel of Perez’s efforts in national politics. Soon after, the Judge retired.

Leander Perez developed a reputation and image around his genteel stature and aristocratic visage. Always immaculately dressed in broad-lapel suits, old-fashioned dress shoes which were only sold at one store in New Orleans at the time of the mid-20th century, a Panama hat, and sporting a fine cigar, his style alongside his rich, kingly speaking voice, with French as a first language to add to its dialectic and accentuated flare, created an imposing and formidable figure to behold. Despite his national appearance as a malicious, recalcitrant, even belligerent, racist and demagogue with a knack for rumbustious rhetoric, Leander Perez dearly loved his family. A devoted family man who fathered four children, he and his wife married in 1917 and remained so until his death. Additionally, his was not withheld from negroes. Within Plaquemines, the local negroes were freely allowed to approach him to ask for work, as was anyone, and the Judge expeditiously found them good jobs. He could find jobs for anyone and successfully got the parish unemployment percentage as low as 1.78%. He used levee board royalties to increase payroll of parish citizens. He often covered legal fees for utterly indigent families. He hosted all sorts of social events and often donated to the Red Cross, American Cancer Society, and donated Christmas boxes to servicemen deployed to Vietnam. There are countless examples to list of his public charity. He was also an ardent advocate of social programs and was responsible for most of the existing infrastructure in Plaquemines by the time of his death. Such incongruous, idiosyncratic nuances comprised the ideologies of the segregationists of yesteryear.

Finally, in 1960, he resigned from his position as district attorney; after which, the Democratic executive committee of the 25th judicial district appointed his son, Leander “Lea” Perez Jr. as his replacement. Last but certainly not least, on November 30, 1967, Perez retired as parish commission council president and was succeeded by his son Chalin, bringing to an end a nearly 5-decade long career in office and setting the sun on the era of Old South politics in southern Louisiana. On February 10, 1967, Agnes Perez passed away, aggrieving him deeply. On March 19, 1969, the Judge quietly passed away from a fatal heart while in his study. A remarkably massive crowd attended his wake and funeral in New Orleans. Additionally, he had secretly reconciled with the Church which had excommunicated him for “racism” and was given a Catholic funeral. As the funeral processions of thousands drove down the Belle Chasse highway to his final resting place, folks closed their businesses and stood by the road to watch and pay respects. Leander Perez Sr.’s casket was interred next to his wife, Agnes, in a mausoleum at Metairie Cemetary in New Orleans.

Leander Henry Perez Sr.’s legacy simply no longer exists within the 21st century. While his sons continued his political legacy, this ceased to carry over to his grandchildren. Unfortunately, very little even exists left to commemorate his memory despite the massive influence he had in state affairs and generosity within his parish as well as its infrastructural development. A forgotten hero of Louisiana’s past, it is still important to remember his efforts to preserve the cultural and ethnic integrity of his state as well as combatting the evils of Communism which seized control over America during his storied lifetime. To conclude with a fair quote about him, following Perez’s death, former governor Jimmie Davis stated, “There are many who might have disagreed with the causes he championed, but there are few who could disagree with the personal sincerity and integrity of Judge Perez himself. He did what he felt and believed was right.”

Bibliography:

“Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr.: The Wallace Movement.” YouTube, January 25, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cUbjUXsX0n4.

Jeansonne, Glen. “Leander Perez.” 64 Parishes, June 28, 2023. https://64parishes.org/entry/leander-perez-adaptation.

Jeansonne, Glen. Leander Perez: Boss of the Delta. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisian State University Press, 1977.

Wasp, Joe. “A Defense of Jim Crow and the South: 2nd Edition.” Identity Dixie, May 10, 2024. https://identitydixie.com/2024/05/10/a-defense-of-jim-crow-and-the-south-2nd-edition/.

“The White people of the South are the greatest minority in this nation. They deserve consideration and understanding instead of the persecution of twisted propaganda.” –Strom Thurmond

This is an interesting essay and I read it from start to finish. But it would have benefited from stricter editing. Especially in the middle section.

Joe Wasp

I have really enjoyed reading this, thank you.

I have an Associated Press book that they put out every year with all of their articles in that year, I’m guessing they still do it, the book i have is for 1966. In it, they show a protest March against the elevation of an African man to the rank of Bishop in the Catholic Church and show pictures of the European Marchers protesting against it.

It seems to me that these social engineers weren’t just out to destroy the solidarity of the South at that time.

It was really nice to see an Article from you again.

God Bless You Sir.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Thank you.