(Note to Identity Dixie readers: The following is chapter XII of my book, The Life and Times of Matthew Fontaine Maury, Pathfinder of the Seas.)

Shortly after President Lincoln ordered Virginia to supply its quota of armed men to put down the rebellion afoot in the state to her south, Governor Letcher called an emergency session of the State’s legislators to discuss the grave and pressing matter, and to decide upon her immediate course of action. Would the sons of Virginia obey the President’s order, or no?

While the Virginians believed their Southern neighbors in South Carolina had acted prematurely and unwisely in seceding from the Union, they also believed the President had acted unwisely and unstatesmanlike in his attempt to compel the Virginians to take up arms against their brethren to the south. They themselves were somewhat uneasy about the newly elected president, and what would be his policies; particularly his domestic policies, or his attitude towards the South. They did not know a great deal about the man, but they soon learned that he most certainly knew nothing of the general mindset in the South if he believed for a moment Virginia would raise an army to invade another state and murder her own kith and kin. And certainly not in the name of preserving a “Union” that many of them believed had already been broken beyond repair.

In the years leading up to 1861 and the inauguration of the new President, a great deal of tension between the two sections of the country – North and South – divided by the so called “Mason-Dixon Line” had developed. With each passing year this tension, far from being relieved except on occasional fleeting moments, continued to advance nearer and nearer the breaking point. With the great and rapid advancements in science and technology occurring during this time, came the promise and general expectation of bringing the Northern states and their Southern counterparts closer together in terms of understanding one another. The invention of steam locomotion and the laying of railroads, as well as the stretching of telegraph cables – both connecting North to South and South to North in an unbroken chain of commerce and intercourse – merely served, as many would begin to notice, to drive a wedge between the two sections. And to drive it ever more deeply with each passing day, it seemed.

What began as a small, yet irate and radical minority in the North, would, over the course and time of things, turn into a powerful political movement, one of whose objectives was the abolition of slavery in the Southern States. By 1860 this motley group of Yankee malcontents had formed into a viable political party and gave themselves the name of “Republicans.” These “Republican” abolitionists had been, for many years prior, agitating for an immediate end to black slavery in the South. But the broader, more expansive goal of their movement, which the skeptical Southerners knew all too well, was to destroy all institutions they deemed to be “slavery” then existing on the continent, and especially that which they considered to be second only in expediency to African slavery. That is to say the “slavery” of women to men, or of the institution of patriarchy, which they had already succeeded in destroying to a large extent in their own states in the North. Unsatisfied with the destruction they were leaving in the North, they would turn their undivided attention towards their continental neighbors in the South.

The South was not amused by any of this, nor was it in the least fooled by the abolitionist pretext to free the poor unfortunate African slaves. They knew that ending African slavery on the continent was merely a pretense for a grander scheme of destroying the traditional South because they knew that the radical spirit of libertinism which had so infected the people of the North could not be contented with merely abolishing the enslavement of a race of men that the abolitionists themselves considered their inferiors. Leading men of the South had made many appeals to their conservative brethren in the North to exert their influence to temper the radical spirit of their abolitionists, but all to no avail; by the spring of 1861, nothing could be done on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line to stop the spirit and tide of war.

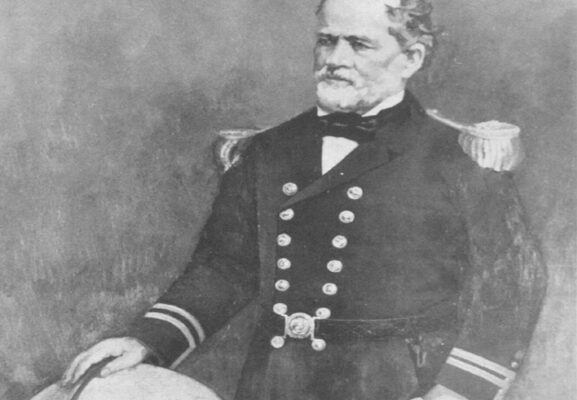

War is the sum of all evils, someone once said. It brings out the very worst in people. On April 20, 1861, Commander Maury, Superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory in Washington D.C., tendered his resignation as an officer of the United States Navy. Thus ended his illustrious career in the United States Navy, and the pursuit of scientific knowledge in the fields of Oceanography and Meteorology he had spent so much of his life developing. In the Union states, his resignation was considered an act of treason, punishable by death. Thusly, a bounty was put upon Commander Maury’s head. Commander Maury was known to be, among people in the North and the South, a man of indisputably high moral character. In order, therefore, to destroy his reputation and turn the feelings of union men against him, stories were made up and leaked to the press concerning the nature of his resignation. One story accused him of abandoning his post without as much as tendering his resignation. Another declared that he had destroyed manuscripts for the new book of his authorship about to be released under seal of the Navy Department. And there were others. All of course intended to turn Northern sentiment against Commander Maury, and all of course untrue.

The only truth to any of it was that Commander Maury had indeed given up his position at the Naval Observatory, and had done so as a matter of duty to his native State, Virginia. Almost immediately thereafter false reports as to the nature of his departure began to appear in the Northern newspapers. As to the most scurrilous of these, Commander Maury would, on May 12th, address by way of letter to his old friend and mentor, William C. Hasbrouck, of New York. To wit:

My Dear Friend,

I only saw last night the remarks of the Boston Traveller about Lieutenant Maury’s treachery, his desertion, removing bouys. It’s all a lie. I resigned and left the Observatory on Saturday the 20th ult. I worked as hard and as faithfully for “Uncle Sam” up to three o’clock of that day as I ever did, and at three o’clock I turned everything – all the public property and records of the office – regularly over to Lieutenant Whiting, the proper officer in charge. I left in press, ‘Nautical Monograph No. 3’ – one of the most valuable contributions that I have ever made to navigation; and just as I left it, it is now in course of publication there, though I shall probably not have an opportunity of reading proof, and cannot tell what errors or alterations may appear.

I have lost none of my interest in these enchanting fields of physical research which I have revelled in there for near twenty years. I am here to war, not against science, but against the oppressor, and for my fatherland. As for “the bouys,” I touched them not! But I am here to defend the right, and will do all and everything to discomfit the enemy that is consistent with civilized and honorable warfare. A price has been set on my head in Boston. I thank them for the honor; for I do not forget that in other days a price was set upon the heads of the best men of that State, and the cause in which I fight is far more righteous than that which moved those great and good men to take up arms against their mother-country.

Yours most affectionately,

M.F. Maury

Notwithstanding Commander Maury’s belief in the righteousness of his cause, his resignation of his commission as Superintendent at the National Observatory caused great alarm among eminent men around the world, some of whom immediately sent dispatches to him, by way of their emissaries in the U.S., offering asylum to him and his family in their countries where he might carry on the important scientific work he had been so long conducting as Superintendent at the Observatory. To one such invitation Commander Maury penned the following letter from Richmond, dated Oct. 29, 1861:

Admiral,

Your letter reached me only a few days ago; it filled me with emotion. In it I am offered the hospitalities of a great and powerful Empire, with the Grand Admiral of its fleets for patron and friend. Inducements are held out such as none but the most magnanimous of princes could offer, and such as nothing but a stern sense of duty may withstand.

A home in the bosom of my family on the banks of the Neva, where, in the midst of books and surrounded by friends, I am, without care for the morrow, to have the most princely means and facilities for prosecuting those studies, and continuing those philosophical labors in which I take most delight: all the advantages I enjoyed in Washington are, with a larger discretion, to be offered me in Russia.

Surely a more flattering invitation could not be uttered! Certainly it could not reach a more grateful heart. I have slept upon it. It is becoming that I should be candid, and in a few words frankly state the circumstances by which I find myself surrounded. The State of Virginia gave me birth; within her borders, among many kind friends, the nearest of kin, and troops of excellent neighbors, my children are planting their vine and fig tree. In her green bosom are the graves of my fathers; the political whirlpool from which your kind forethought sought to rescue me has already plunged her into a fierce and bloody war.

In 1788, when this State accepted the Federal Constitution and entered the American Union, she did so with the formal declaration that she reserved to herself the right to withdraw from it for cause, and resume those powers and attributes of sovereignty which she had never ceded away, but only delegated for certain definite and specified purposes.

When the President elect commenced to set at naught the very objects of the Constitution, and without authority of law proceeded to issue his proclamation of 15th April last, Virginia, in the exercise of that reserved right, decided that the time had come when her safety, her dignity and honor required her to resume those “delegated” powers and withdraw from the Union. She did so; she then straightaway called upon her sons in the Federal Service to retire therefrom and come to her aid.

This call found me in the midst of those quiet physical researches at the Observatory in Washington which I am now, with so much delicacy of thought and goodness of heart, invited to resume in Russia. Having been brought up in the school of States-rights where we had for masters the greatest statesmen of America, and among them Mr. Madison, the wisest of them all, I could not, and did not hesitate. I recognized this call, considered it mandatory, and, formally renouncing all allegiance to the broken Union, hastened over to the South side of the Potomac, there to renew to Fatherland those vows of fealty, service and devotion which the State of Virginia had permitted me to pledge to the Federal Union so long as, by serving it, I might serve her.

Thus, my sword has been tendered to her cause, and the tender has been accepted. Her soil has been invaded; the enemy is actually at her gates; and here I am contending, as the fathers of the Republic did, for the right of self-government, and those very principles for the maintenance of which Washington fought when this, his native State, was a colony of Great Britain. The path of duty and honor is therefore plain.

By following it with the devotion and loyalty of a true sailor, I shall, I am persuaded, have the glorious and proud recompense that is contained in the “well done” of the Grand Admiral of Russia and his noble companions-in-arms.

When the invader is expelled, and as soon after as the State will grant me leave, I promise myself the pleasure of a trip across the Atlantic, and shall hasten to Russia, that I may there in person, on the banks of the Neva, have the honor and the pleasure of expressing to her Grand Admiral the sentiments of respect and esteem with which his oft-repeated acts of kindness, and the generous encouragement that he has afforded me in the pursuits of science, have inspired his

Obedient servant,

M.F. Maury, Commander C.S. Navy

Very interesting to learn that he was offered sanctuary by the Tsar’s brother, the Grand Admiral of Russia! I’ve also been given to understand that the letter was delivered by Prussian emissaries who also wanted to convey their respects.

Yet, I’ve also heard that the Tsar of Russia offered aid to Lincoln’s administration, in which their Navy played a large role, in subjugating the South. If true, at least the Commodore in his reply gave them all a lesson in the true nature of the conflict. Was this possibly a 19th century precursor to Operation Paperclip?

Yes. I’m thankful that letter has been passed down to posterity for that reason alone. As you know, it is said that Commander Maury was making great strides in Britain turning the hearts of her people in favor of the South, and that this was, in large part, why the Lincoln administration made the emancipation of Southern slaves a priority of the war … after the fact.

Ha! Interesting question. Never considered that before, but one supposes it is possible.

Thanks for the interesting comments as always, German Confederate.

“I touched them not! But I am here to defend the right, and will do all and everything to discomfit the enemy that is consistent with civilized and honorable warfare.”

These are excellent words, and those we embrace.

Reading our ancestors, and their eloquent oratory, reminds me of how degraded our society has become.

Quite. I have included the contents of that and many other of Commander Maury’s (et al) eloquent correspondences at other websites in reply to people who fall for Yankee revisionist history degrading our Southern patriots and heros, hook, line and sinker. Almost invariably when I do, someone or other will reply with a remark indicating his or her surprise at the remarkable prose of the writers in those correspondences. Their Yankee educations have them believing our forbears were a bunch of uneducated backwoods hicks who could barely read and write, if that. Of course, truth be told and as Dr. Dabney points out in several places in his own writing on the subject, even Southern blacks were better educated than their white counterparts in the Yankee states.

Thanks for the comments, FatherDabney.