(Note to Readers: Links to parts I and II of this series are embedded in part III, here. In this fourth part of his speech, Judge Rogers continues listing the unbroken chain of events leading to Southern secession and the War of Northern Aggression, citing the murderous madman, John Brown’s, infamous raid on Harpers Ferry, in his futile attempt to incite armed servile insurrection in Virginia, with legislative enactments in several northern States nullifying the fugitive slave law duly enacted by representatives of the whole people assembled in Congress. Exacerbating the situation was, as stated in a previous part, the unstatesmanlike conduct of powerful demagogues in the north, kowtowing to the demands and basest impulses of the lowest elements of their constituencies; namely, those who called themselves “Republicans”; who formed the “Party of Lincoln,” or, the “Grand Old Party,” if you prefer.

I do not hesitate to say that I disagree with Judge Rogers on at least two points in this part of his speech. These are, (1) when he states that the legality/illegality of secession was settled *forever* on the side of illegality by the South’s defeat in the war. This has been a spirited point of discussion between myself and others for at least a couple of decades. “Forever” is a long time, and of course we here at ID believe the question was settled *temporarily* at the fall of the Confederacy, but certainly not “forever” in the term’s strictest sense, or, “while the earth remains.” Relatedly, (2) where Judge Rogers pronounces to his audience any future secession movement could only result from what he terms revolution, “which, God forbid,” in his words.

For my part, counter-revolution is the proper terminology Judge Rogers failed to articulate in that passage, the true revolutionaries having been the Yankees and their northern acolytes all along, which the totality of Mr. Rogers’s speech otherwise documents very well. For my part, moreover, God Bless, and keep, and bring the counter-revolution to its righteous conclusion, in His time! I personally seek and look forward to a Free Dixie, by which I mean, a Southland freed from corruptive northern and Judaic influence and coercion; a truly self-governing Southland. I seek this for the sakes of my children and my grandchildren, and for all of our posterity, as do many of you.

We Southern Nationalists are not, nor have we ever been, “revolutionaries” as a matter of principle or fact; we are, have ever been and shall ever be, counter-revolutionaries – dedicated contrarians and oppositionists to the perpetual revolution initiated hundreds of years ago in Mother Europe, brought to New England’s shores amongst the ungovernable “stranger” elements aboard the Mayflower and beyond (**see e.g. William Bradford’s, “History of Plymouth Plantation,” specifically his preface explaining why the Mayflower Compact was hastily written to begin with). In any case and without further ado, we give you part IV of the 1902 Confederate Reunion oration, “The South Vindicated,” by Judge John H. Rogers, at New Orleans.):

“In addition to the action of various Northern States in nullifying an act of Congress, John Brown had, in October, 1859, heading a band of armed conspirators, invaded the State of Virginia, seized the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, and was pursuing a concocted plan to arouse the slaves of Virginia to insurrection, to plunder, to murder, and to overthrow the government of that State.

“Judge Taney, second to no one who ever sat on the Supreme Court bench, unless it be Marshall, was assailed in the bitterest and most vituperative terms for his decision in the Dred Scott case. The solemn judgment of that court was audaciously and insolently set at naught as arbitrary and void. The whole North was angry and convulsed; the voice of law was silent.

“Mr. Lincoln, the President elect, and the idol of his party, had said:

The Union cannot permanently exist half slave and half free.

“In the campaign of 1860 Mr. Seward had affirmed that:

There was an irrepressible conflict between freedom and slavery.

“It was equivalent to a declaration of war by the most prominent and influential statesmen of the victorious party upon an institution peculiar to the South. The people of this generation cannot comprehend the intense excitement and deep feeling existing in the South, and the bitterness growing out of this question between the sections. The South had two billions invested in slaves when Mr. Lincoln was elected. The Constitution had been nullified already. His position on the slavery question was well understood.

“Such is a dim portrayal of the situation by which the South was confronted in 1860. What had she to hope or expect in the Union? No such conditions had ever previously existed. No such consequences had provoked New England to threats of disunion. It was not a question of the control of the government, or an economical or industrial question; it was not a question of preserving the balance of power or the equilibrium of the sections, such as was felt in New England when the Louisiana and Florida purchases were made, and Texas acquired. It was a question of civilization, of constitutional liberty, of the preservation of the principles of the Constitution; and the South, when the alternative was presented of abandoning the principles of the Constitution, or giving up the Union, with alacrity, but with the deepest reluctance that the necessity existed, chose the latter. She was overcome, she has suffered, but she ought not to be maligned or misrepresented.

“I must not be misunderstood. The whole question of secession and disunion has been forever settled, so far as the domain of constitutional law is concerned. The decree was rendered at Appomattox, and was written in the best blood of all sections of this land. It was rendered in the court of last resort, where all the laws but those of war are silent. From it no appeal can be had except to revolution, which God forbid.

“From the clear skies His blessed finger points to a restored Union, and His beneficent smile is spread all over the land where dwells a people, the strongest, the most enlightened, the most prosperous and happy to be found on the habitable globe. In all our struggles we have not been forgotten; His mighty hand has been felt, lifting us up from our calamities, chastened but made better and stronger by His loving kindness. “For whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth; and scourgeth every son whom he receiveth.”

“Slavery has been called the trembling needle which pointed the course amidst the tumultuous discussions of our Congresses until the war between the States began. But the South did not go to war for slavery alone. Thousands and thousands of soldiers from every State in the South, perhaps not less than eighty percent of them, entered the army willingly and deliberately, and served through the war, who never owned and never expected to own a slave. It was unmistakably interwoven among the causes of the war. It was inseparable from all the great industrial, economic, and sectional questions involving the policy and control of the government. It embittered the discussion of every public question, and afterwards embittered the great war itself.

“It was inextricably interwoven with the cause of the Confederacy. It brought down upon it the prejudices of many in this country who believed in the great principle for which the South contended, but who would not identify themselves with a cause involving the perpetuation of slavery. It brought upon the South the moral sense of foreign nations. It taught us what Washington, Jefferson, and Madison had long before recognized – that the moral sense of mankind did not sustain it. It was the bane of our social order, and it was the chronic cancer which gnawed at the vitals of our future greatness. It perished, like secession, as one of the incidents and results of the war. Thank God it is gone forever!, and that we have a reunited country under one flag, the emblem of a free people in an inseparable Union of coequal States, and never destined, we pray God, to become the emblem of imperial power at home or abroad, or to float over vassal States and subject peoples anywhere against their will.

“Ours was not a war of conquest; it was not a war of pelf; it was not a war of desolation; it was not a war of fanaticism; it was not a war of envy and malice; it was not a war on defenseless and homeless noncombatants; it was not a war of coercion. Ours was a war of self-defense, a war for home, for self-government, for State sovereignty, for the right to peaceably withdraw from the Union into which we had voluntarily entered, but to which no power had been delegated to coerce a State. It was a war to establish the true lines between the powers reserved to the States and those delegated to the general government. It was a war to preserve our form of government as the fathers understood it when it was framed.

“No higher encomium can be rendered to the South than the fact, sustained by her whole history, that she never violated the Constitution; that she committed no aggressions upon the rights of property of the North; that she simply asked equality in the Union and the enforcement and maintenance of her clearest rights and guarantees.

“The South had no hatred for the Union. The highest evidence of that is that the Confederate Constitution was substantially the same as the Constitution of the United States, modified so as to make clear the construction for which the South had always contended. There were few other changes; and they looked, in the main, to the correction of abuses and errors which experience had discovered. It distinctly inhibited the foreign slave trade, prohibited their introduction into the Confederacy from any other Territory or State except the slaveholding States and Territories of the United States, and gave the Congress the power to prohibit that also. True, it recognized slavery, as did the Constitution of the United States, and afforded like guarantees.

“No, the South had no hatred for the Constitution, and no hatred for the Union. It was her Constitution and her Union, in common with all the other States created by the wisdom and courage of all their sons. The ashes of her children consecrated the battlefields of the Revolution. They had led suffering and half-clad, but victorious armies for American Independence. Washington and Henry Lee, Marion, Sumter, and Pinkney, John Paul Jones and George Rogers Clark were among her illustrious soldiers in the great struggle for independence. Camden, King’s Mountain, the Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, Eutaw Springs, and Yorktown were all hers.

“It was our Andrew Jackson, commanding Southern soldiers – largely Kentuckians, Tennesseans, and Mississippians – who fought the battle of New Orleans, terminating the war of 1815, the war which has been called the second war of Independence, the effect of which was “to vindicate our equality and independence among the nationalities of the world.” It gave us a position of dignity, importance, and power which has never been diminished. It was a wholesome agency in promoting national unity, in developing national patriotism and courage, military and naval skill and ability, in quieting for many years sectional discord, and demonstrating our unaided competency to defend our soil and coasts, and to cope successfully with the best-disciplined army and the most formidable navy of the old world.

“In this centennial year of the celebration of the acquisition of Louisiana Territory, I can hardly resist the temptation to suggest what might have been the destinies of the Great Republic if the pre-vision of Thomas Jefferson, a Southern statesman, had not comprehended the tremendous importance to the commercial development of the United States and the preservation of the Union that the “Father of Waters” should forever remain under their control. But this digression, however inviting, cannot be indulged.

“The names and battlefields I have mentioned cannot be separated from the Union any more than the light from the sun. The history of the South, with all its tender memories and glorious triumphs in war and in peace, were bound up in the history of the colonies, the Confederation, and finally in the Union. Why was it not dear to her people? Why should she not desire to preserve it? Why should five millions of people, as a single man, rise to leave their father’s house, but for some overshadowing cause and impending danger. In all history did ever like occur?

“And when the North determined upon coercion, did ever any people stand together as did the people of the South? With her ports blockaded, cut off from the outer world, with no army or navy, destitute of arms and ammunition, almost without manufacturing industries of any kind, the South for four years conducted, single-handed and alone, against the trained army and navy of the Union, backed by the extensive industries of the North with its enormous population and wealth, with its immense shipping and commerce, and with its legions of mercenaries from other lands, the most stupendous war of modern times.

“Do these old veterans themselves realize the achievements of the armies of the Confederacy? One in whose accuracy I have implicit faith states that more than half as many men were enrolled in the Union army as the entire white population of the Southern States proper, including all the women and children. The records show that more than two million, eight hundred and fifty thousand troops were furnished the Union army by the States; and while, for the lack of official data, I cannot state, to a man, the enlistment in the Southern army from first to last, the estimate has the sanction of high authority, deemed reliable, that the Confederate forces available for action during the war did not exceed six hundred thousand soldiers, of whom there were not more than two hundred thousand arms-bearing men at any time, and when the war closed, half that number covered the whole effective force, of all arms, in all quarters of the Confederacy.

“Besides the disparity in the land forces, there was the Federal navy, the gunboats and the ironclads, without which many believe Grant’s army would have been lost at Shiloh and McClellan’s on the Peninsula. When the Union army dissolved, four hundred thousand more men were borne on its roll than the estimated enlistments of the Southern army, from the spring of 1861, to the spring of 1865, and during that time there had been two hundred and seventy thousand Federal prisoners captured.

“Three hundred thousand Federal soldiers sleep in eighty-three beautiful Federal cemeteries, rightly cared for by the government, to tell to posterity the awful story of that mighty fratricidal conflict. How shall we account for these things? Has all history afforded a parallel? What is it that made the South a unit and molded its armies for terrible battle? Let the unpartisan and truth-seeking historian of the future answer; but whatever his answer may be, if he could challenge the respect of mankind, let him not say the cause, the sentiment, the conviction, or whatever it was that inspired them to brave and noble deeds, did not have the abiding faith and solemn sanction of her armies in the field or her people at their homes.

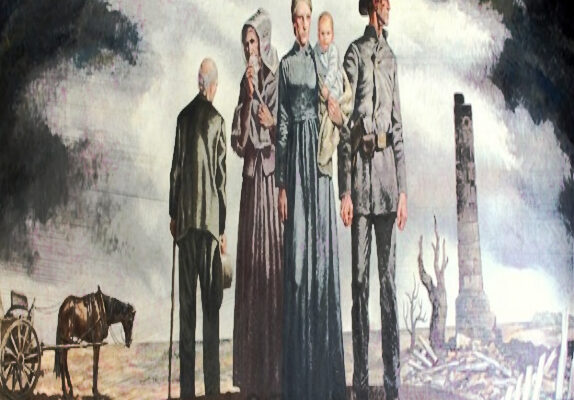

“Until the ragged and half-starved remnants of Lee’s and Johnston’s armies laid down their arms and accepted the cold, stern award of defeat; until the ever-increasing and overpowering numbers of Grant’s and Sherman’s armies made battle no longer possible, unfaltering they stood together without a murmur, still hoping against hope for the triumph of their cause; and when the end came, and disaster and ruin met the eye on all sides, and when at every fireside was a vacant chair; when blackened chimneys identified spots where happy homes had stood; when poverty and want stalked abroad; when aliens came to rule that they might plunder; when ignorance and audacity flaunted themselves in high places, and corruption had its ready and rich rewards, still they were true; true to themselves, true to their comrades and the memory of their martyred dead, true to their old leaders, true to their great captain, and true to their States and to their beloved South.

“Their armies had gone down in defeat, their cause had failed, their fortunes had been swept away, disappointment and sorrows and strange conditions hovered on all sides and darkened all the ways; but there was no treacherous and cowardly turning, to fix upon their civil or military leaders the responsibility for the origin or results of the war. They had staked everything for a principle in vain. Courageous and true, they accepted their fate, and turned again to build up their wasted fortunes and prostrated commonwealths.” […]

[To be continued in Part V]

**“I shall a little return back and begin with a combination made by them before they came ashore, being ye first foundations of their government in this place; occasioned partly by ye discontented & mutinous speeches that some of the strangers amongst them had let fall from them in ye ship – that when they came ashore they would use their own liberty; for none had power to command them, the patent they had being for Virginia, and not for New England, which belonged to another government, with which ye Virginia Company had nothing to do. And partly that such an act by them done (this their condition considered), might be as firm as any patent, and in some respects more sure. The form was as followeth. […]” –

William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, Book II

One comment

Comments are closed.