(Note to readers: Below is chapter VI of my book, The Life and Times of Matthew Fontaine Maury, Pathfinder of the Seas. Additional chapters may be found on my contributor pages, here.)

By the year of our Lord 1848, Lieutenant Maury had become a seasoned Navy veteran of some 23 years’ service. He had, by this time, distinguished himself, amongst men of good will and not a few of high rank and prominent standing. He was universally acclaimed among these classes as both an indefatigable man of science and industry possessing a gifted original mind, as well as a first-rate Navy Man dedicated to bringing fame and glory and honor to his countrymen, and to the fledgling United States Navy. Nevertheless, every man of fame or distinguished abilities has his enemies and detractors. Matt would be no exception to the rule. But he also well understood the proverb pronouncing that “a prophet is not without honor, save in his own country…”

Some years before in 1839, Maury would become the victim of an unusual accident, which would bring his career as a seaman to an abrupt and painful end. This untimely accident would occur on return from a visit to his aging parents back at their farm in Tennessee. Having given his seat inside to a young woman and her baby while traveling in conditions of cold and inclement weather, Matt was obliged to take his seat next to the driver atop the coach conveying its passengers to various destinations on its route to New York, Lieutenant Maury’s destination. When the coach unexpectedly took a slide on a muddy embankment in the dark of night along the way near Somerset, Ohio, Matt was suddenly and violently thrown from his perch, and straightaway deposited onto the unyielding earth below. As with his fall from the tree in his youth we read about in a previous chapter, Matt was immediately rendered unconscious by force of the impact. And likewise, as with the previous accident, restoration of consciousness soon revealed to him the severity of the injury he had on this occasion sustained. For in this present case more permanent and debilitating damage would be the result.

Upon inspection of the mangled limb, it was determined that the thigh bone had been fractured longitudinally, while the leg was simultaneously displaced at the joint of the knee. The leg was hastily put aright and temporarily immobilized, and Matt would take up residence at a nearby inn to begin the difficult recovery process. The length of time and difficulty of Matt’s recovery were made the greater when it was later discovered that the hasty first setting of the leg was improperly done, and that, unhappily, the procedure must therefore be undertaken once more.

Toward the end of his shore leave between assignments in the year 1831, Matt became engaged to Miss Ann Hull Herndon, the young maiden whom he’d first met on visiting his widowed sister-in-law and her orphaned children in Virginia six years before. The two lovers would later say that their first meeting was an instance of “love at first sight.” During his time away at sea, the two friends occasionally corresponded by letter or as frequently as circumstances at sea would permit. Days at sea quickly became weeks, weeks turned into months, and months accumulated into years at sea hundreds and thousands of miles distant. During one voyage aboard the U.S.S. Vincennes, a voyage on which ship and crew would circumnavigate the world, Matt would spend four long years away from home port. But absence would merely serve to make the hearts of Matt and Miss Herndon grow fonder, one toward the other.

Several lengthy sea voyages now behind him, little Miss Herndon had by this time grown six years older and into a very handsome young woman, and Matt thought the time ripe to formalize his fondness for the maiden and his desire that they should one day become husband and wife. At their engagement in 1831 Matt presented to Ann a little seal he had purchased for her to be used exclusively for sealing the envelops bearing the letters she would thenceforward write to him while he was at sea. The seal bore the simple Hebrew inscription Mizpah, which being interpreted means, “the Lord watch between thee and me when we are absent one from the other.”

By the time of the coach accident in 1839, Mrs. Matthew Fontaine Maury and her husband had been married five years and had begun to start a family of their own.

A barque is a type of sailing vessel or ship consisting of three or more masts; the fore and main-masts in this configuration being rigged square, while the aft-most mast called the mizzen is rigged, contrary its counterparts, fore-to-aft. The mast on a sailing ship is that beam or beams raised perpendicularly to and supported at its base by the ship’s keel.

When a mast is “rigged square” it means that a sail-bearing beam smaller in diameter than that of the mast is attached at the smaller beam’s center perpendicular or crosswise to its larger main mast anchored securely to the vessel. When a mast is rigged fore-to-aft, this means that, by various means of rigging, the mast is rigged with the line of its sail running forward-to-aft or bow-to-stern, longitudinally aligned with the ship’s hull. The former, then, is a rigging more or less aligned cross-ways to the length of the ship’s hull by use of a second beam; the latter in line with it and without the need of the second beam. A barque, then, is a sailing vessel or a ship bearing three or more masts configured in such a way that the forward masts are all rigged square, while the mizzen mast is rigged fore-to-aft.

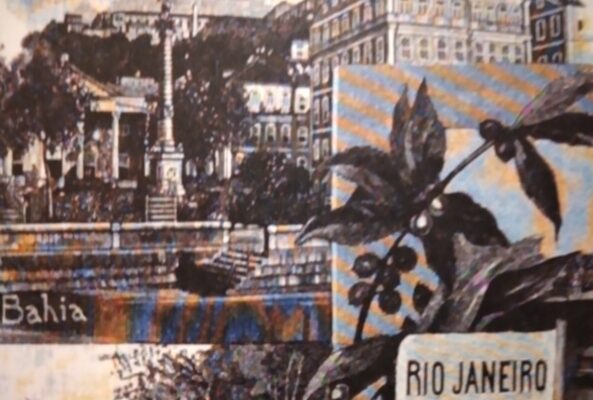

In such a vessel was to be put to their first test Maury’s newly published sailing directions in 1848. The port of destination ascribed would be Rio de Janeiro, a much-frequented South American port at the time and on the average some fifty-five days sailing distance from New York. Maury estimated that from ten to fifteen days would be cut from the voyage in both directions to any vessel following his sailing directions, thus yielding a sum of between twenty to thirty days or three to four weeks’ time saved on the round-trip voyage. In truth, he believed even more time would be saved in both directions, but his habit was to err on the side of caution in his estimations. The voyage itself would yield its own results, and not a few cautiously optimistic seafaring men would await the final tally with hopeful anticipation.

Some years before, the intrepid young sailor had been appointed sailing master of a ship whose first destination was to be Rio de Janeiro. On shore leave in anticipation of setting sail for this voyage, young Maury would, in accordance with his life’s ambition to “make everything bend to my profession,” seek to establish the quickest, most efficient route to the South American port. To his dismay, Maury would soon discover that little had ever before been collected, let alone organized, in the way of charting winds and currents to or from this frequented destination. It was somewhat surprising to Matt that seafaring men dating back to Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan had been largely “groping in the dark” to find the best and fastest routes in their journeys to foreign ports. Yet, undaunted by the dearth of recorded information as to winds and currents at sea, he took it upon himself, should opportunity be given him, to collect and provide it as comprehensively as his meager abilities would permit. Establishing its usefulness and veracity would be another matter.

While young Maury labored daily through the lengthy recovery from the unfortunate accident which had stranded him in Ohio, his active mind was employed about the business of providing a quicker, safer, and therefore more efficient route to Rio de Janeiro and other seaports around the world.

“If I could somehow determine when, where, and at what velocity the most favorable winds and currents might be found on a given voyage to a given seaport at any time of year,” Matthew thought, “this would most assuredly yield the happy results of shortening voyages to ports around the world by days, weeks, or perhaps even months.” And as with the proposal for publishing his series of geography textbooks later in life, Matt believed that to essentially bring friendly nations closer together by way of shortening sea voyages to and from ports by days or weeks or months, was certainly a way to make himself useful to his profession, and to his fellow man.

There were related problems which by this time had come to occupy his restless mind as well. Chief among them perhaps, his belief that the fledgling U.S. Navy was in desperate need of the establishment of an academy for training young midshipmen similar to and of equal importance with that of the now long-established Army Academy at West Point. At West Point, it was said at the time, a young man could receive the finest education in the higher branches of erudition America had to offer. The Naval Academy of Matt’s conception would one day rival that of West Point, joining its rank among the finest institutions of higher learning yet to be established on the North American continent.

With a view to convincing the American public of the necessity of re-organizing the Navy such that it would soon become the envy of maritime nations around the world, Matt set about to accomplish with his pen that which his physical condition would otherwise prevent. This new pursuit would take the form of articles and longer essays in which his ideas for improvements to the U.S. Navy would be propounded and explained for broad public consumption. These writings would appear in magazines and other popular publications, under the curious title “Scraps from the Lucky Bag,” written under the nom de plume, “Harry Bluff,” to conceal Matt’s identity.

Early in the year 1848, the barque H.W.D.C. Wright of Baltimore, Captain Jackson commanding, set sail for the port of Rio de Janeiro with the intention to either prove or disprove both the theory behind Maury’s sailing directions, and the reliability of the entries circumscribed for that time of year in his Winds and Currents Chart for the Atlantic Ocean. Whatever might be the final outcome, Captain Jackson determined to follow the directions given on the chart without deviation, laying aside for the purpose all doubts and preconceived notions his long years as a seaman had taught him to the contrary. And happily so, for H.W.D.C. Wright would smash the average sailing distance to that South American port by twenty days on its outbound journey, and by no fewer than fifteen days on her voyage home. Thus began one of the most astonishing eras in maritime history the world has ever known.