(Note to ID readers: The following is chapter VII of my book, The Life and Times of Matthew Fontaine Maury, Pathfinder of the Seas. A few other chapters of the book may be found in the pages of my contributor by line, here. -TM)

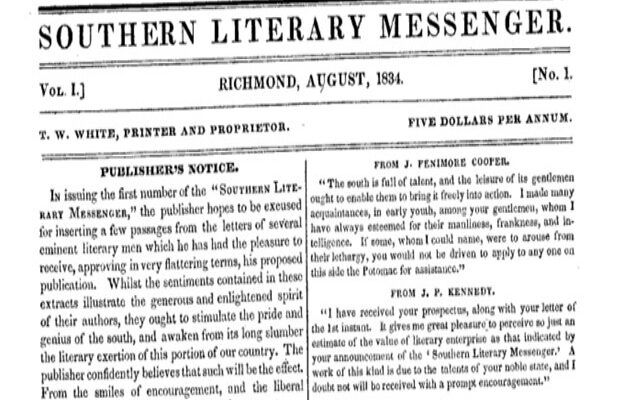

The Southern Literary Messenger was established in Richmond in 1834 by Thomas Willis White. At the time of its establishment most American periodicals were published in northern cities like Boston, Philadelphia and New York. These were the great seats of America’s literary voice. Consequently, the national literary voice bore a distinctively northern character and complexion. Thomas White’s primary aim in starting the new magazine was, as he wrote in its maiden article, “to stimulate the pride and genius of the South, and awaken from its long slumber the literary exertion of this portion of the country.” In other words, White believed northern literary dominance was not good for the South or her future, nor in fact the country as a whole, and that therefore the entire country might benefit by the resurrection of the Southern Literary Voice which for so long had been dormant.

By late December of 1839, Maury believed himself in sufficiently fit condition to complete the return to New York his untimely injury had impeded three months before. The ship to which he was attached had, in the meantime, been delayed in harbor, and he hoped to arrive back in New York prior to her departure. For passage he would board a sleigh, as a heavy blanket of snow now covered the route. Along the way, however, the carriage encountered numerous difficulties, the cause for which, at length, he would not arrive in New York in time enough to board the outbound vessel as he’d planned. Thus being his fate, Maury would enjoy the company and hospitality of his New York relatives, Ann Maury and Rutson Maury, for a few days before, with permission of the Navy Dept., making haste to his home in Fredericksburg to reunite with his wife and their two young daughters.

In August of 1840, Maury wrote to Rutson of his “panacea for ennui.” He had, in February of the same year, written to Ann of the reason for which he apprehended the leg might prove to force his early retirement from the Navy. Having “no power to keep the knee from sinking beneath me,” Maury secretly confided in Ann, he further conveyed his apprehension that this would spell doom for his burgeoning career as a Navy man. While he awaited word of its plans for him from the Navy Department, Maury occupied himself with writing and seeing to the dissemination of his “Scraps from the Lucky Bag,” under the nom de plume, “Harry Bluff.” The Southern Literary Messenger would be his primary vehicle for publication of the little “scraps,” and Thomas White would make young Maury editor of that magazine from 1840-1843. Ennui is a French word meaning, roughly, “my loathsome burden”; a panacea is its cure or antidote. Thus was young Maury’s panacea for ennui put to good and profitable use in his new position at The Messenger.

Early in his career as a young midshipman, Matt was required to study the Spanish language, in addition to his other duties. Owing to what he called an “accident of education,” he would later write, “I seldom or never feel lonesome.” Matt’s panacea for ennui was the pen “dipped in the inkstand for friends far away”; the “accident of education” in his allusion was in reference to the necessity under which he found himself as a twenty year-old midshipman – “searching for grains of knowledge among bushels of chaff.” In order that “nothing would be lost” in preparing himself for testing before the Navy Department’s Board of Examination, the young midshipman procured a Spanish work on navigation and began to pour himself into study of its contents. Matt was beginning to learn early in his career the meaning and propriety of the phrase “killing two birds with one stone.”

Despite the fluency of his pen and the beauty of his prose, Matt had ever been his own worst critic when it came to his writing. He wrote to his cousin, Rutson, that “if the next collection of Scraps from the Lucky Bag should appear to you a little outre, you will know the cause.” The “cause,” he had previously revealed to Rutson in the same letter, was attributable to “the want of books and proper teachers in the Navy.” Not a few of his Scraps from the Lucky Bag were written with a view to alert the general public to the selfsame cause inflicted upon all Midshipmen at the time. The effect of which, at length, would cause the government to supply the want. Or so he thought, and hoped. And to his pleasant surprise, his little “scraps” were equally popular amongst his fellow citizens and his fellow sailors alike.

When it was later discovered who this mysterious “Harry Bluff” was, Matthew Fontaine Maury became a household name throughout the length and breadth of the country almost overnight. Shortly thereafter newspaper articles began to crop up in some of the nation’s most widely read and respected publications extolling Lieutenant Maury’s unique abilities and eminent qualifications. The public then began to insist that Maury be appointed to some important post in the Navy whence his expertise on Navy matters could be put to its proper use.

Ever restless to resume his duties as a naval officer, Maury wrote to the Secretary of the Navy in 1841 suggesting that his crippled leg would not interfere with his ability to perform his duties as an officer aboard ship so long as his appointment were to one of several posts “which do not call for much bodily exercise, as of flag-lieutenant for instance.” This letter was sent in secret from Richmond in anticipation that family and friends in Fredericksburg might intervene to defeat the application should they discover his intentions. Notwithstanding the precautions taken to prevent their intervention, however, Judge John Taloe Lomax would indeed learn of Maury’s petition and, by and with the aid of written testimony from three of the town’s best physicians, convince the Navy Secretary that Lieutenant Maury was, despite his remonstrances to the contrary, in no condition to endure the rigors of sea life no matter how light the duty he should be assigned.

Meanwhile, exposure of Lieutenant Maury as the author of Scraps from the Lucky Bag quickly turned into talk of how best to put his talents and expertise to work in the Navy. The National Intelligencer would be the first publication to suggest that Maury should be the Navy’s newly appointed Secretary. Other prominent publications would later join in the chorus as well. And for a time, it looked as though Maury would indeed be the selection. But a cabinet post was not a position Maury himself sought or believed suitable for his personal talents, ambitions, nor disposition, so he persistently declined the honor until, at length, the fervor for his selection began to subside and finally abated. On Jan. 26, 1841, he wrote to his parents concerning the matter:

My Dear Parents, I do not think there is much danger of my having a cabinet position inflicted upon me. The newspapers continue to discuss the subject, though, with much earnestness. That I should be thus brought forward and commended is, of course, exceedingly gratifying to me, as I am sure it must be to you also. In these times of party rancour and bitter political strife, high places in the State edifice are far from being desirable to those who value peace of mind.

Still, there must be some important position in the Navy Department that would be both satisfactory employment to Lieutenant Maury himself, and from which his peculiar talents could be put to their most broad and extensive use for the benefit of the whole country. But what might it be?

Lucy was suddenly startled back to consciousness by a sharp rap at the front door. The old Commodore had not been awakened by the knock, and was yet fast asleep. Lucy was glad her father was getting some much needed rest. She could hear bits and pieces of the conversation in the parlor. Someone of importance, it seemed, had come to pay his respects. The voice was too muffled; she could not tell who. She glanced over at the clock and was surprised to read the time; she had been asleep for over an hour. As she raised herself from her chair, the contents of her lap fell to the floor below. Reaching down to pick up the mess, she let out a soft chuckle at what her eyes beheld; not only had she forgotten what she’d been doing when she dozed off to sleep an hour earlier, but she could see that in her slumber not a stitch had sewn itself. She reckoned she had better get back to her work as her little niece for which the present was being knitted was due in with her parents on the morrow. But first she would check with her mother to see who had been by to pay a visit.

Interesting to learn that Maury, in addition to his many other abilities, also had a very engaging writing style, and maybe rubbed elbows with Edgar Allan Poe at the Southern Literary Messenger?

German Confederate:

There is a chapter in the book partly dedicated to explaining Commander Maury’s youthful interest in becoming a “Navy Man” to start with – boiled down, he wanted to follow in his elder brother’s – John Minor Maury’s – footsteps. The elder John Minor got stranded on NukaHiva amongst the natives of that Pacific Island for two years during the war of 1812, before he was finally rescued by an American frigate and later led an expedition to destroy the Barbary Pirates then playing havoc on the country and its commerce. This was of course way before Melville wrote “Typee.”

Commander Maury certainly “rubbed elbows” with many of the eminent men of his day, including General Lee, et al. Indeed, it was General Lee who finally talked Maury into re-patriating to Virginia, and secured to him his chair at Washington College in those post-WBTS years prior to both of their deaths. As I’m sure you well know, during his exile, Commander Maury was working feverishly with Maximilian to secure a new homeland to Southerners and Virginians in northern Mexico. I was just reading, in point of fact, the disagreement between Maury and Dr. Dabney on point only last night. Turns out Dr. Dabney had a better “prophetic” understanding than did Maury with respect to what was about to befall the Emperor Maximilian, and why, therefore, Maury’s efforts were all in vain. Not of course that the two men disagreed on the principle of the matter, but Dr. Dabney was simply better equipped to see that Maximilian’s days were numbered, and that, therefore, Maury’s efforts in this vein were bound to fail. …

Thanks for the comment, sir.

You’re a fund of fascinating information! I hadn’t been aware that Maury taught at Washington College after the war. I’m intrigued also to learn of John Minor’s exploits on the Pacific Islands. I’m guessing it’s possible they also had an influence on Poe’s ‘Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym’. It’d be nice if Identity Dixie would have a conference sometime where like-minded people could share ideas in person. (probably have to keep it on the down low so it wouldn’t become another Charlottesville). We’ve all read different things and can learn much from one another.