Not long ago I brought a pair of friends to the Joshua Chamberlain house, in Brunswick Maine. By way of background and introduction, Joshua Chamberlain was a famous Union officer during the Civil War. But as with many characters from the War, he should not be regarded as a mere war token. He was a scholar, first, and a statesman, second. His career as a soldier was quite incidental. Brunswick is a town in Maine, north of the cesspit that is Portland and south of Augusta where our otherwise fair state’s finest sheisters malinger, sustained by taxes and necromancy. Brunswick is a historic town, which is not to say all Maine towns are not by proxy, but Brunswick boasts a high yield of historic districts and monuments. The Old Church, the College, as well as, a plethora of maintained or otherwise restored homes such as the aforementioned destination of ours, the Skolfield-Whittier House and up.

That all being said, I brought my friends there as a means of exposing them to snapshots of New England culture as we have had it before the decidedly deleterious changes of globalisation had settled themselves upon every regional culture you can contrive or imagine. We achieved this end. Time spent in the Chamberlain house reveals much about how life was for us, or at least our privileged few. One can, if they are a carpenter’s apprentice like myself, marvel at the elegance of the routing done to the trim, the curvature of rounded walls, the coffin corners, etc-etc… One can smirk at the occasional amateur mistakes in the joinery, or note with subtle pride where curators had moved walls, rearranged pipes or transferred lally-columns.

Bereft of that added experience, one can see the bygone elegance and dignity of our ancestors. The stately portraits of a man’s beloved mother. The stodgy, haughty pride of a Puritan minister’s grandson, now a Congregationalist preacher. There is the freeze-frame of the man himself in the form of busts commissioned after his death. Of course, and this prompts me to submit this article to you, there are the war bounties collected from the battlefield. Southern Antiquities. A square War Flag surrendered at Appomattox still remains. The signatures of those signing away the Cause of the South to the North. There are letters from Confederate soldiers who kept correspondence with Chamberlain, and even visited him after the War’s end. I did not expect from our private tour to derive any great and personal appreciation for the South beyond the feeling of solidarity I feel, shallow as it may be, knowing that one and all the American peoples were betrayed and used by the Federal Government, this includes the Union Army which was the federal apparatus of vengeance.

Speaking of the man. Among other points gleaned from a quick trip, it dawned on me that in many ways Joshua Chamberlain served as an archetype of the North as it could have been, juxtaposed to the South which seems to have her own archetypes, which by extension I am less capable of fully understanding. If you have the chance, there is a book I would recommend, being Albion’s Seed by David Hackett Fischer. It is a wonderful book, with what I think is solid anthropology and sociology, describing the folkways of the four earliest strains of American, then broadly English, life. Chief among them were New England, but here truly Massachusetts and her ill-begotten Province of Maine, and Virginia.

Massachusetts, settled by Puritans, is described as a land with peculiarities. Industrious, studious, seeking the glorification of the community through personal excellence. New Englanders were not a warrior people, and her aristocracy were more oft than not either the educated or the religious. Social consciousness and conformity of culture were of utmost priorities. These traits, the Puritans believed, would best usher in God’s Kingdom on Earth. No one man could accomplish this divine mandate, and so the value of individuality, while not absent, was largely and obviously subsumed by social duty. Chintzy slogans like “it takes a village to raise a child,” reflect some truth here. Our climate was harsh, and so, I am told by foreigners, is our demeanour. Our embrace of these virtues, even when the particular appeal of Puritanism faded, resulted in the mutation of our stock into the more commonly understood phenomenon of the WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant). His greatest weapon was the Protestant Work Ethic, and he prized duty and education above most things. He was a passionate man, but the passions were to be tempered at all cost, with emotional compromise being the worst of weaknesses. These traits allowed the WASP to become a clever breed, when the fire of Christianity lessened, it was absorbed into the fires of learning, of knowledge and pursuit of perfection. You can see these attitudes in many of the Founding Fathers, their belief in man’s perfectibility, their enlightened attitudes and openness to the sciences and new ideas, as well as, their insistence that the passions be tempered, moderation embraced and strict etiquette enforced and demanded. And while they were not obviously all Yankees, you can see clearly how the attitudes of the Founders, who for some typified the proto-Yankee, laid the foundation for the ascendant Northern aristocracy. For all the good that does us now in a world where globalism enforces a lowest common denominator and being a tryhard is a liability.

The Southerner, in Albion’s Seed typified by the Virginian (which I reckon must be no more fair than typifying all New England by Massachusetts) is, by contrast, the son of English Cavaliers. Theirs was, in starker contrast, a warrior aristocracy. The distinguished feature of Robert Edward Lee is used as a model of the gentleman soldier, whose virtues Virginian boys were taught to seek – even before there was a Robert Edward Lee. These virtues were will, independence, strength and skill. The individual was glorified through support of the community. In some ways, the archetypes are described as inverse of one another. From an early age, the Virginian was said to have been praised for singularity of mind, willfulness and willingness to embrace a cause of conscience. It takes no great stretch of the imagination to conceive how this would make the Southerner uniquely qualified to excel in the theatre of war. And, I am told, to this day the Southern states contribute a disproportionate volume of her sons to war efforts in many places. Wars instigated by powers whose motives should be, I think, checked. Quite rigorously. The Southern aristocrat was said to be sympathetic in some ways to the royalty of the Old World. Highborn Southern families gave their children distinguished names hearkening back to the Teutonic heroes of our shared patrimony. Their families had remarkable coats of arms which would have been the envy of barons and baronesses. Aristocracy as a word when spoken, was perhaps not done tongue and cheek, as it is in the North. Indeed, it has been noted, that despite the propaganda, men like George Washington who can be said to have come from the budding aristocracy of the South, were pained by the prospect of disunity with the Old Country and flew the old English and British flags as long as their consciences would allow. Or, perhaps more cynically, convenience. Still. Whatever the case, the virtues listed are listed. I can neither confirm nor deny them and their accuracy or echoes of reality, but I respect them. Certainly, the Virginians I have met have all been feisty, especially the women – and that is not without charm, in an otherwise polity ridden world.

So there from Albion’s Seed is condensed a sketch of the conflicting archetypes. One can see without any difficulty how those two might be moved to conflict, even if that conflict was not natural – which whether true or not we can never know because of how the chips fell. It is true that Puritans and Cavaliers had their differences, sometimes loudly. But in all fairness, the whole of the Thirteen Colonies had differences. We began in this country as a collective of ethnostates, viably speaking, with cultural biases and affinities. It should surprise no one to learn there were cultural differences that some perhaps less than beneficent caste of overlords could exploit for their own perceived gain.

And with that we come back to the man by way of digression. Joshua Chamberlain hearkens back to that stubborn Yankee archetype. Here was a man with no business on the battlefield. He was a man from wealth, well-travelled as wealthy Yankees were wont to be. He was culturally sensitive and tracked with figures now famous in their own right, such as Longfellow who had a room near Chamberlain’s study and is preserved to this day for posterity. He studied modern languages. When the War came, Chamberlain was moved by civic duty – an easily manipulable trait – to enlist. He was denied. He had no experience, he had no business in war. He was told to go off and be a scholar. Now Chamberlain eloped from Bowdoin College, called the Harvard of the North, where he was being schooled. Upon transferring to another school he managed to persuade an enlister to see to it he was drafted. Owing his intelligence and good looks (for all the good they would do a soldier) he was made an officer.

In some ways, his absolute lack of military credibility proved to be an ironic asset. The tactics he developed were so hideously unorthodox that many regimented, educated and militarily keen Southerners were incapable of understanding them. Of course, war being ugly, had prices. Despite his bookish beginnings, we are told that Chamberlain was a man of no mean courage. He faced death often. And suffered for it, having nearly been killed on a number of occasions. He was hit with a shell with left him mauled, shot in the foot. Of course, this is common knowledge. It is his peculiarities as a man I might illustrate here, which resonate with those of us steeped in New England.

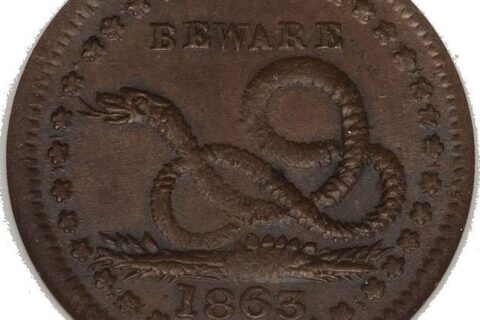

Chamberlain was a keen collector of things, as many Yankees are. A Confederate soldier cornered him once, and by sheer stupid luck, managed to misfire his revolver – which Chamberlain swiped and kept, because I could see from my trip, Confederate revolvers were VERY handsome. Beautiful swarthy woodwork on the grips, brass trigger guard, some engraving on the cylinder. Artful. Something I think of the old Teutonic tradition of carrying weapons with soul. Of course, it seems to me that where the North had an industrial juggernaut, Southern gear would have had more personality, more weight, as it were. So it goes. Chamberlain collected swords from prisoners, various things which he preserved for the point of transmitting the experience. It strikes me as a very Yankee thing to do, in the midst of bloodshed and violence, to somehow summon the mind to say, “Well hey, you never know when this will come in handy.” I know this is the case, because in my own family were soldiers who brought home swords which over time lost their origins – swords which I saw were curiously similar in shape to those hanging on Chamberlain’s wall, right down to the oakleaf embossment in the leather grip of the hilt, and again on the brass pommel. Perhaps some fine day or other, when Yankee thrift allows me to part with the sum required, I might take them in to be identified. I digress, he kept the trophies as a reminder of the experience.

Experience was an important thing, evidently. And while one can say what they will of the War, it was important for Chamberlain to do what he felt the right thing was. He did not want to leave the theatre with unfinished business, or a tarnish on his moral career. When the surrender of the South was nigh, Chamberlain received it. He was chosen because he had diplomatic skills. He was also chosen because he was said to have held the South in high regard. It was relayed to us that when he led his men to the site of surrender, that he bid his soldiers stand and give homage to Fellow Americans. This might be seen as an important lesson for us today. And yes, while it might be regarded as easy for him to say, being on the “right” side of victory, the equal-opposite argument can be made that “no,” it is not easy. Many conquering leaders would have been less graceful. Would a Sherman have instructed his soldiers to see the Southerners as equals? When shady deals were made on a train in France, were the vanquished Germans treated with that kind of dignity?

Chamberlain was a shrewd Yankee. No doubt he knew that affording his brethren (for the great tragedy was many fighting, or those refusing to fight knew the South was just that – brethren) some grace was not only just, but pragmatic. For, if scorned, why should the South ever show loyalty again? These are no doubt practical questions a sound mind like his would have entertained. And I am not ashamed to say, I find the character of Chamberlain more sympathetic than a Sherman or a Grant. Chamberlain saw gore, and left some of himself – literally – behind at Round Top. He was catheterised during that battle, and would forever suffer with it for the bullet which struck his side, and should have killed him.

And there again, that Southerners came to Chamberlain after the War for visits, speaks volumes. None forced them to do this, nobody demanded their gentlemanly respect between men of conscience who by cruel fate were found on opposing sides. But there was a component of chivalry, which despite all the differences to be found among the sons of Puritans and Cavaliers, was stronger than what had divided them. What having divided them being a Federal Government bereft of chivalry, of course we now all know, I think North and South alike. For me, this little snippet was an enlightening experience, to think of how strong the morals of some of these men were. I had known that Robert Edward Lee was a man of great chivalry, but what I did not know was that we had our own archetypes as well. Which should not surprise me, given that I know well that the Federal Government does not represent me, nor my interests, nor my home, or her interests. It follows that New England’s truer sons, left to their own devices, will not reflect the image that the Federal Government which operates in our name portrays. Still, it is good to have your faith confirmed.

As a side note, in closing. Our docent was a Southerner, a delightful old man from – you guessed it – Virginia. He apologised for his lack of Yankee twang, confessing at one point it seemed strange that the Chamberlain museum should be curated by a Dixian. I found it fitting. Here was a Southerner who had come North, and developed a firm respect for a Yankee much in the way many Yankees will (with varying degrees of openness) admit to respecting General Lee. As you might imagine, my exposure to Southern culture is limited in scope. So, I have no grasp on what internal mechanisms our docent overcame to achieve his position. As a boy, I was taught a narrative regarding the Civil War. That was about it. If the establishment victim needed a convenient illustration as to White villainy, there was a gradient scale. Peak clandestine villainy was German. Erudite establishment villainy was British. Common vulgar villainy was Southern. Heroes were generic, unaccented Americans – bland. I recall no great coloured villains. I no longer have cable, so I don’t know how much this has changed, if at all. What remains is that despite the veneer of America, we are all still walking on eggshells in some ways. In the same way I am cautious not to step on the Virginian’s toes when I encounter her, or him, so was the Virginian careful not to step on mine. Mutual respect being what it is, I suppose.

Seax is a father, craftsman and Nationalist, as well as a dyed in the wool Yankee. He specialises in esoterica ranging from Teutonic religion to New England history, with a keen interest in understanding, mobilising and rectifying America’s regional identities. He can be found trying to rally the clans in Maine – wish him luck.

Hello Seax,

This is a nice piece – very well written. I especially love “Albions Seed” and I am glad to see how you wove it into the article. Having been educated in New England, I interacted with many a legacy Yankee – not the Northeast ethnics, who are a different breed altogether – and I find the description of Chamberlain to be a solid Yankee archetype, albeit from a bygone era. The Copperhead Corner is a great complement to Identity Dixie.

Cheers!

Padraig Martin

Thank you. That means quite a lot, seeing as I’ve read a handful of your (and other) articles on this site. It was the essay comparing Yankee and Southron attitudes toward government which prompted me to follow someone’s suggestion I submit stuff here. I’m glad I did.

The Revolver you mention was without a doubt made in hartford connecticut By Colt. The engraving was a sort of anti-counterfeiting mechanism – Only colt could roll engrave their cylinders like that.

But i think your point remains the same.

Indeed? That’s good to know. It makes sense. And I suppose it’s possible our guy could have gotten his piece from the factory and had it retooled. Either way. Thanks for that sleuthing, that’s good to know!

Seax,

You write: “It should surprise no one to learn there were cultural differences that some perhaps less than beneficent caste of overlords could exploit for their own perceived gain.”

Truth sir, saddest truth.

It’s a pity that the ‘educated’ Mr. Chamberlain didn’t discern this truth, (as did many educated Southerners such as R.L. Dabney and D.H. Hill), and lend his martial talents to the Southern cause.

Education has been a weapon used for some time against us. It’s all too easy to see consensus as a false positive market for truth. They count on this.

May I ask: the Northerners who lent aid to the Southerners, were they called “Doughboys” there? Here, that’s what they were called by the establishment. Likely among other less charitable names.

Bless’d, too, is he who can divine

Where real right doth lie, 30

And dares to take the side that seems

Wrong to man’s blindfold eye.

For right is right, since God is God;

And right the day must win;

To doubt would be disloyalty, 35

To falter would be sin.

-Frederick William Faber ‘The Right Must Win’

The Yankees saw Truth (and everything else) as marketable and negotiable. “Where a man’s treasure is, there will his heart be also.” If you reply that the South lost the war, I’d direct you to Dabney’s ‘The Duty of the Hour’ address in 1868 at Davidson College.

John Pemberton was a Northern man who lost as much for his choice to go with the South as any man. He was even maligned by many Southerners for the surrender of Vicksburg! … Still, he did the right thing.