Trigger Warning: this posits the better known American Civil War from the perspective of Maine’s anti-war movement as heralded by the Maine Democrats, Secesh “party” and infamous Copperhead movement. Sensitive language and unpopular interpretation of recorded history follow. Caveat emptor, you’ve been warned.

If you’re still with me, this essay follows in the wake of this.

As with anything, don’t take one man, woman or self-aware automoton’s word for it. Go read for yourself. Books, lots of books. In the article and in the train of thought preceding this one, I made some statement or other approximating the observation that objective truth is better seen in the rear-view mirror. I will write about the anti-war presence in Maine, focusing predominately on the Civil War, where I find the most illustrative learning lessons. At least for the America contemporaneous to the period I find myself writing this. Much of the impetus for later paragraphs will come from an issue of the Maine Historical Society Review, Civil War Edition. However, in full disclosure, you’re going to have to trust my memory on the rest, as my conclusions have been formed from reading a plethora of books, many of whose names escape me.

By the time of the “Civil War,” the projection of the New World as an extension of its admittedly disputed English masters had since been legislated away. The Founding stock of this country, English-Americans, had been reduced to a mere cog in the then-still Northwestern sea of “White Americans,” or whatever ease of convenience term we might label our transitory brethren. We can argue where the salad bowl tossed and melted somewhere else. Suffice to say, the ethnic backdrops which provided the archetypes blending into the broadly illusory American idea still had memories of the Old World. (It would take too many entries to disambiguate all sides and opinions, facts, and fictions. To do so would also exceed my acumen and powers of memory retention. The sad truth is that my articles are poorly researched, they exist as a reflection of what the author has crammed into his memory banks and has held onto.)

Where I shall begin is with a reference to a book I have read, being Albion’s Seed. The case is often made colloquially and in passing that the Civil War was a brothers war. And it was, of course. Cousins fought cousins, divided by the artificial divide of the Blue and Grey. It was a truly superficial and obvious political war. One should have to go no farther than reading the mutual Constitutions of each colonial power to uncover this barely hidden truth. It is clear from a cursory inspection of the Constitution of the Confederated States of America that they had no overpowering desires for grand revolution. They are a mirror of the Thirteen Colonies before them. Indeed, part and parcel is that the Thirteen Colonies extended into what became the Confederacy.

Virginia was a sister to the Bay Colony, at one point. And we know from written records that it was a sisterhood beset by troubles, as with any family. The Virginian Cavaliers were from one part of England apart from the Bostonian Puritans who came, more or less, from the townships constituting the region of East Anglia. Virginians waxed monarchic, while Bostonians waxed rebellious. To this day, we speak of a Southern aristocracy. New England’s aristocracy is different, inasmuch as Boston could reach the various corners of New England. Now, I shall add: New England was not a uniformly Puritan State and likely never was. Maine was peopled by Englishmen of a different stripe, and here we eventually made peace with the French (outside of sibling-rival jokes foreigners never understand), while in Boston the religious hegemony was strong. Now you must understand, that even in Boston’s Sacred Heart was the pinprick of wicked, dare I say “popish” Anglicanism. (The Puritans justified rebellion in part based on the erroneous assumption that Anglicanism was a vehicle of Popery.)

At any rate, I made that long, wandering point to make this one. We, being Virginians and Mainers, would have had relatives of the same name remaining in Jolly Old England. So it goes. So, when one says this was a Brother War, it was. Now, in that same breath, I can throw a wrench into things. By the time of the Civil War, this country had access to a number of flags apart from Old Glory.

One cannot help but notice that the flags that flew over the North evolved from the King’s Colours, which had not yet evolved to incorporate the St. Patrick’s Cross which fills the Scotch Saltire behind the Cross of Saint George which was, and is, the rightful emblem of the English people whether trenchant in England or in diaspora elsewhere. All New England Revolutionary flags have roots in the Saint George Cross – a perfect example is the “Bunker Hill Flag,” which in truth is nothing more than an English Blue Ensign defaced with the Pine tree/Oak emblem of New England. That same Blue Ensign’s grandchild lives on today as, among others, the Australian, New Zealander and former British Hong Kong flags. The South certainly seems to have found what the North had not yet; which is the St. Patrick’s Cross, the famed “Rebel Flag” (which apparently was never the Confederacy’s national flag) is a composite, one can clearly see, of the colours of Saints Patrick and Andrew. It is the inverse of the North’s, in that it does not incorporate the English Cross. It’s no wonder, we know that the South absorbed an enormous volume of Celtic blood, as many pioneers were of Celtic extraction. But then, the Irish were used as blunt proxy armies by both sides, in addition to occasionally being impressed by the British Army as late as the War of 1812. But, the generals of both sides of the futile Civil War often had the blood of old English aristocracies in their veins. Not always, but often. So there we have it.

It really is worth exploring further, but I promise I’ll stop soon. I want to remind you, that to view this whole sad ordeal in pure modernity is a dite of a fallacy. The Irish were slow to consider themselves American, and to this day to scratch an Irish-American is to see how quickly that hyphen drops and the Irishman remains. It was not a Civil War between two Americas, or even one. Like the first fratricide to establish American independence, it was a firm battle to reassert ethnic status quos. It was a war to lead us closer to the generic American. But with the first, those fighting would not have openly accepted that fate. Virtually all Founding Fathers died calling themselves Englishmen, the generous and egalitarian called themselves English American as we see at the Taunton Flag monument. Then, as always, monetary concerns trumped tribal.

Hopefully, I have painted something of a picture for you as to why I find the topic of the Civil War frustrating. With that being said, in the Northeast, specifically Maine, there was, as I began with – a history of revolt against war. History likes to deny this, but racial solidarity was always an impetus in opposition to war. Over the course of the following paragraphs I will make the case for this, or try.

In the Revolutionary War, popular (often subverted) historians give a number of basic accounts for reasons for Loyalism. Almost all of them omit ethnic loyalty. While powerful tribal loyalty would be harder to exercise across the sea, it was not impossible. But by 1776, not so long that families would have died out, there were still correspondences to the Motherland. There are records. The Colonists, if not British like the Empire, were still English. Many quite proud of this hegemony. As of 2008 when he died, my Grandfather called himself Englishman and American interchangeably. That’s not nothing. And I know, it’s not common. And this is fine. I’ve made peace with that. In a way.

More common, and thus oh so very logical, reasons are given. Money. The Empire provided financial security and a connection to the trade winds. This is debatable, given that the Colonists occupied a low rung of the British ascendancy. Vanity, we know, was a driver to rebel – the Colonial Government wanted equal parliamentary representation which was barred to it on a number of grounds. Of course, this is an oversimplification, but there you have it. Rights and liberties are often listed, the token blacks of the Empire who achieved conditional “equality” under British Common Law would have been far more indebted to the Crown which (politically, anyway) cared about their welfare more than a gaggle of Englishmen jealously guarding their rights and perceiving that they were being displaced by foreigners for the purpose of cheap labour. Huh. Big think.

There were, of course, close relations. Higher education was often still ordered in the Motherland. Our gentry and leaders were no strangers to Old England, even if they felt London was foreign. (It probably was.) The British routinely conducted visits to New England, and relations were not hostile – we’re told, until they were. And there is, of course, the question of family connections. I still have living relatives in Britain. And while I have never sought them out because there has been no connection in at least four generations, I know they’re there and I know roughly where. Relations weren’t always that loose. Pointless wars do well to sever ties, but ties were harder to sever then, than now.

So, there is a double-entendre to consider before proceeding. When it comes to the South and the North, the North remained Yankee land, an expression of post-British and often English dominated life. The South’s aristocracy was often culled from that same root. They both could trace roots to Old England. And, of course, Southerners left families behind to go become who they are, just as the Northerners who left become those Southerners. You feel me? While it’s not fair to say wholesale that the rest of the country was borne of Northern ambition, we lent a lot of genes. That hadn’t been forgotten. And neither did ties to the Motherland cease with the signing of the Declaration, nor even the Flag Resolution which struck our Cross down.

But alas alack, all that goes before and beyond is words, words, words. In so many words I can talk about the anti-war vein of Maine. In the book Albion’s Seed, a line of thought struck me. It was not warriors that England sent to settle the tip of the New World. The Bay Colony was uncovered by the designs of English merchants. It was peopled with Puritans because that was expedient for the Crown at the time. In England, the Puritans were a nuisance who were a perpetual thorn in the Anglican Establishment’s side in a way few other less antagonistic religious groups could be. The long and short, the Puritans were not a warrior people. They could be moved to fight, but it was not their first inclination. Something similar can and should be said of Maine. There is a reason our seal features a landsman and seaman.

Yes, when history speaks of us they shall sing the modest praises of the Maine 20th Volunteer Infantry. Some can even tell me what their flag looks like. Fewer still will know the bloody red Maltese Cross which was the badge of our army. But, most will proclaim the great fervour for freedom which Maine is supposed to have, and the unity of spirit to boot. Our great and impenetrable love of liberty and willingness to fight and die for the Union against the Confederacy. And then? Gobbledygook. One Maine inventor made a repeater rifle, it killed some people. Ear muffs, I think. Somebody sees Bigfoot every now and again at the 7-11, but later have to retract the story because it turns out it was Aunt Mabel from the County. But, like a lot of the gloss and veneer the U.S. likes to bathe itself in, the grain beneath the laminate is rather rough. As with many things, the real reason Maine went to war was…

Massachusetts.

There is a sense of state rivalry between Massachusetts and, I believe, everyone else. Maine’s beef with Massachusetts is the butt of a lot of jokes. Somebody else with more laughs in their tank can tell them to you. I don’t care for the grudge humour as much as I used to. What I will say, historically, is that the tension with Massachusetts stemmed from their ownership. And, if you understand tourist economics, how that imperious attitude never fully collapsed. Maine began as a province, same as Massachusetts. Not only do we not get credit for technically being here first, because nobody remembers, they tend to begin our history with our emancipation from Massachusetts well after the War of Independence. That’s a background grudge, but it isn’t a small one. You might not have to stretch your imagination far to see that Maine did not always want to be thrust out in front of the host as Massachusetts’ spear.

I have struggled somewhat whether to add this soliloquy to what shall pan out to be a rather bloated essay. But, there you have it, digress is what I do. I also like big thinks, and I cannot lie. Well, anyway. I cannot lie well. Whatever. In any given conflict wherein later we have the privilege of judging in reserve, we have to factor in why these wars happen. And why we shouldn’t too harshly judge those who fight in what those of us who oppose the generality of war consider to be largely fruitless endeavours. For a long while we have had the appearance of high trust societies. These high trust societies have been peopled with those who had no reason to suspect treachery. In many cases, politicians were homegrown boys whom you met at a tavern, not the visibly separate oligarchs they now are. “We” and “of the people” meant something different, and it did even until fairly recently. For a man to live a life which requires him to question every word that comes from above is unnatural, and it is why visionaries and dissenters are rare birds. Most acted in accordance with their conscience, despite the disastrous outcomes. I digress.

Maine had her share of visionaries. We’ve always been a clever state. Wicked friggin smaht, deah. In fact, I cannot complete a single commute to any job in any direction without seeing some obscure and poorly understood testament to Maine’s disinterest in the warfare of other states. If I drive through Buxton, I pass Tory Hill, which is my favourite example. That is where Maine regimental soldiers refused to fight in the War of 1812. Their refusal to fight is complicated, but suffice to say, in those days that neck of the woods was rustic and the mere act of living there would have cost significant mental resources. Add warfighting as a cherry to an otherwise unpalatable cake, and you have salty Mainers. There are other examples. Many townships were slow to send sons to both the Revolution and War of 1812. Again: life was hard here then, we had Indian attacks and inhospitable climates to rebuff. War was not a priority in all things. It was for some, and there had always been garrisoned pikemen and the like.

So, we come at last to the promised topic of the attitudes of Maine anti-war patriots during the Civil War. Some of these attitudes, their consequences, and lessons are, I think, very much still relevant. Even today. So please, bear with me. The information I shall hereafter present will be repurposed from “Maine and the Civil War,” from Maine History; Volume 48, January 2014. Specifically, it is inspired by the essay therein contained by the name of “‘We Respect the Flag but…’: Opposition to the Civil War in Down East Maine” by one Timothy F. Garrity.

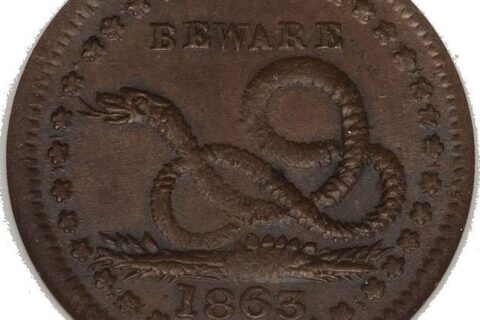

First, the title. It seems to me to be the very encapsulation of the “I’m not rayciss, but______” spirit of today. Secondly, Mainers expressed themselves in a number of ways – as we are wont to do. Some were staunch, brusque, and outspoken. Others quietly voted with their feet by refusing to enlist, dodging the draft – some had to resort to self-mutilation to do this. Some more extreme forms of resistance came about through wholesale rejection of the American flag, which some Copperheads destroyed, and some Copperhead strongholds withdrew from the liberty poles. This would have sent a powerful message. The American flag has always held sway over her people, as we read in Woden Teachout’s Capture the Flag. So it went. The reasons for this come in their plenitudes. War is financially irresponsible. Maine had a tremendous cadre of farmers whose livelihoods could be utterly smashed by prolonged absences. There were also moral dimensions. The war was by many considered foolhardy and nationally dysgenic. The dissenters were labelled Copperheads, a slang for anti-war protesters, and symbolised by a venomous serpent.

There is, I think, a historical irony to make mention of. One of the Banners of Freedom most treasured to Americans to this day is the Gadsden flag, which features a coiled rattlesnake. The snake in the grass which would strike if tread upon is the superficial meaning. I know that many argue for a considerably deeper meaning of the Gadsden Serpent hearkening back to the symbolism of the Ouroborous conceptually hidden in Stuart Dynastic art and architecture, personal heraldry and on. However, as this is debatable I make an honourable mention of it and invite others to stake their own claims as to the metaphysical properties one could assume for the Serpentine Banner. What remains is that the Maine peaceful protesters were seen much as the flag is now interpreted, as coiled snakes waiting to strike. We shall see the reverse is true. Maine protestors against “the war” were doxed before this was a word, abused, and economically destroyed. It all begins to feel very familiar. Almost as if seldom, if ever, do good men in their throngs learn from the naked lessons history can teach.

The Copperheads frequently made use of old Indian Head pennies as lapel pins, facing the Goddess Libertas out. They did this believing themselves to be true upholders of the Constitution, that to engage one’s own country in war was to defeat the principles of unity theoretically fought for to withdraw from Britain. The name itself, Copperhead, replaced the former inflammatory labels such as Tory. Who were they? History records the Copperheads as being predominately foreign, often immigrants, who were also Catholic. That is the popular image of the Copperhead, an enemy insurgent in almost every sense. Not Anglo-Saxon, nor even Americanised. Maine’s Copperheads provided a glaring rebuttal to this image. In Maine, the whole “no popery” thing was more than a slogan at this time. It was a lifestyle choice. Popery was not welcome outside of Portland. The majority of dissenters were rural men with no stake in such things. And they were no fools. By Union Brass, the Copperheads were regarded as a much direr threat to the war effort than any Confederate. This isn’t to insult the battle acumen of the Southerner, as it is generally understood that the Southerners whose aristocracies were often Cavaliers – were, in fact, warriors. Thus, the Army of the South was considered to be “better.” But it remains, the enemy within is always more dangerous than the enemy without. The enemy within knows your mind, he is you. The enemy without is not, and therefore cannot – unless he is a turncoat and traitor, a real fear the Union officers faced in assessing Copperhead strength.

We know that the Copperheads were active from the beginning. In some ways, it echoed some of the sentiments of the first Civil War, being the American Revolution itself. At this time, Maine was majority Republican. Understand this might not mean what a modern reader thinks it does. Republicans were more liberal, whereas Democrats were often more clannish in nature. (Think “Southern Democrats.”) Maine’s Democrat minority held strong reservations both about President Lincoln, and regarding the prospect of war. 4/10 votes were cast in favour of anti-war candidates with no further qualification.

There are compelling reasons for their reticence. Among the chiefs are: the United States would be unable to compete on a world scale should it dissolve into petty states as it had been before the Union. Furthermore, the underlying concern was that an internally divided country would be far less capable of self-governance and would forever be the concern of hostile alien nations who might capitalise on their weakness and division. One can see many of these concerns echoed in Lincolnite speeches. What with divided houses and all. Something about standing, I think. Lincoln’s agitating for federally imposed war was initially rebuffed. An emergent pattern with American war history, and neglects to make notice of, is that it is at times incredibly unpopular and requires significant media cooperation to impel. The attack on Fort Sumter is commonly regarded as a casus belli, but many Mainers were unconvinced that this was true. They remembered statements such as “it is not in my jurisdiction to abolish slavery where it exists,” (paraphrased) and were irate when this statement was countermanded by another from Lincoln to the tune of “slavery was somehow the cause of the war.”

There is a clear racial component, and it isn’t hard to understand why, then, it would have been a sticking point with our salty ancestors. Under the thin veneer of non-intervention, which has been a default position of the American dissident, was a seething cauldron of emotion. Let us not forget an accusation lobbed at New England in recounting history. The British Empire was, despite being at times Anglocentric, if your Anglophilia was geographically expedient, still multicultural, as well as, multiracial. When abo culture became fashionable among the genteel citizenry of Great Britain, and other imperial powers we should add, an element of racial animus did fester among some Colonists. For example, under certain technicalities, Britain began freeing negroes at a rate which White indentured servants couldn’t hope to match. Special attention was given to the negro which was not given the White Colonist. Indentured servitude is the condition under which a huge cadre of White Colonists from England arrived, in which they sold themselves into tenured service. A service which, if the truth is told, often had poorer benefits than actual slavery. Yes, I know, citation needed. Maybe another time. At any rate, the above applied to England’s poor. And the British Empire did at this time still favour her English. The Irish suffered horrible dispossessions and fortunes, many of which might have been avoided. These bad things happened to them while the media of the day touted the cause of “freedom,” and “liberty” under God and all that jazz – for the fashionable trophy cause of the day which has remained in perpetual circulation since.

So, let us consider those whose stock built up Maine’s foundry. From the beginning was a helping of French, who themselves were no strangers to being brutalised by their government with proxy causes. And who themselves were not ashamed to use these tactics against the English settlers resulting in lengthy fratricidal, and frankly, sublimely unproductive combat. There were, of course, us, the English settlers who would go on to form the (debatably successful/stable) solvent into which the Generic Americans would someday breed. There were some Irish from the beginning, albeit in smaller numbers.

Memories are not always a short thing. To this day, in my neck of the woods, there *can* be tensions between Unhyphenated-Americans (who are often largely Anglo) and the French. These downplay into comic rivals which vacillate between the generally bemusing and the tiresome and unproductive. The same is said of the Irish, who had strongholds such as Limerick fairly early. Though, in fairness, Maine’s Irish were most likely already Anglo-Irish and were diluted at a much more rapid pace than Boston’s late coming Irish. Maine’s early Irish were likely not thoroughly distinguishable from her English. If they were not absorbed into the early English breeding pool like the minority of Borderer Scots that accompanied some of the earliest waves. Whatever. It’s a moot point, at this stage in history. An idle curiosity, at that, for those who spiral in the purity hole that circles the drain to hours of wasted thought.

The long and short is this: Maine had little experience with the negro at this time. For that matter, it is unlikely much of New England had great recourse to care. The cause of the Revolution for American rebels was over the procurement of English rights felt entitled by the Crown to the Colonists. Rights that for hundreds of years we had fought bloody civil wars in the Motherland to acquire, only to see them given out like party favours to those who understood precious little of the massive symbolism of all that was fought for. Thus, many negros became loyalists and fled to Canada, those that the unforgiving snow didn’t outright kill were often granted imperial passage to other warmer climes. And then again, there were the other ethnicities that make the fabric of American life. We know the urban (read Massachusetts) Irish were much more in tune with their feelings than their English counterparts, and entirely more willing to express them with rather less talking and thinking. They expressed their intolerance in outright violence. Lynching of the negro population in Irish controlled areas was frequent.

But, the Englishman is not polite forever. In Maine, the newspapers controlled by the Maine Democrats initially began their exposes with questions about the validity of the Federal Government’s aims. They called to court the hypocrisy of the Fed for denying the South the right to self-determination. Such was a thing the Maine thinkers seemed to recall was very important to some of their fathers. States’ rights, was the rallying cry – in the beginning. Besides, the argument went, the Constitution technically safeguarded the institution of slavery as it related to limited government and the theoretical framework of state sovereignty. These arguments failed to impress the folk who were going to go with the flow impressed upon them by the Federal Government and the Republican media of the time. These arguments led to many commanders of Maine garrisons to deny the admission of negroes into armed service, claiming theirs was a White man’s war and no concern of theirs.

Ultimately, the Maine Secesh and Copperheads reasoned: the war would divide White Americans, benefit foreign influence and lead to unchecked damage that could last for many generations. And, to this day, there are those who bicker over this particular fratricide as though it were somehow any different than any other proxy war Whites have been forced to shed their blood over in defence of others. The Maine anti-abo papers did nothing wrong. In my rear-view mirror of perfect reflection, of course.

When their logical assertions failed, the Copperhead and Secesh papers resorted to polemics. There were many papers making use of inflammatory rhetoric, such as calling the abo cause “n*gger philanthropy,” and “n*gger agitation.” A rather interesting claim is made that Lincoln was a Confederate “cipher,” otherwise unable of independent action acting on behalf of unseen Confederate agents. More on that, I think, below. There are a few quotes which precede the Maine Democrats’ refusal to fly Old Glory. “[We have] with sorrowing hearts witness the black Flag of Abolitionism waving over a divided and disintegrated Union.” And “we respect the Flag but despise his [Lincoln’s] piratical n*gger worshipping crew,” leading to “[we have] warned their countrymen against the troubles we are now experiencing, and feel as though, having done their duty, are not responsible for the present war.“

It was observed upon Lincoln’s movement to gather troops following Sumter that his actions belonged formulated in a mind beneath a crown. This could not have occurred under the old [Revolutionary] Government. It was tyranny. How could the Union be preserved through spurning the affections of our Southern brethren? Brethren. Jefferson Davis did not wish to invade Northern territory, after all. Taxation increases mercilessly to raise an army, prices Maine cannot pay. The cost would plunge much of the country into destitution.

When these logical beseechments inevitably failed, invocation of brutal honesty followed. The popular press of the day liked to show the war in flowery, Victorian terms of heroism and triumph. The Maine Democrats presented a darker truth. Crushed skulls, impaled youths. Friendly fire. Permanent disfigurement. The starvation of wives and children at home – a terrifying price which shall soon be discussed. The cost of war was, and is too high.

If the Union entered the war and won, as many were certain it would, than a horrible unforeseen but easily foreseeable cost would be imposed. Following the published opinion that if the men of the North were to sacrifice their blood, than the South must concede to forsake its slaves. A war that nobody asked for, some added. To this, the Maine Democrats rebuffed; they called the institution of abolition “inhuman” and implied it would release sable hordes upon the South who would do little but unleash rage and hatred. Such a policy violates the conventions of moral warfare, they insisted, for in so doing they would release a million negros strong who, quoting “are capable of doing an immense work in the destruction of human life.” Some Maine Democrats went as far as to claim that “only an end to of the race in the country would put an end to their murderous work.” Strong words, for a peacenik. In Minecraft. And all that shit. When that didn’t work, they called their opponents “negro worshippers.”

The response to increasing tension is probably predictable. It was violence. And doxing, before it was cool and sexy. Following swift accusations of disloyalty and unamericanism, the free press of the dissenters was stormed by mobs. Some were burnt down. Others smashed and broken. Many of their (very expensive) presses were melted down for bullets. Even to this, there was resistance. One Marcellus Emery was said to have given a fiery speech as he waded through the violent mob, reckoned 2,000 strong. The data I have does not say what happened to him. Part of his speech goes, “…maintain their liberties and to protect a free Press, which is their best guardian.”

You might think the powers that be would be something to be ashamed of. It was not, the fervour of virtue signaling is always supreme. Rather, the perpetrators of the actual violence boasted. These were not isolated incidents. Good Republicans would always, and everywhere, rise up and smash any dissent. And with more violence, if permissible. It was not the acts of ruffians and brutes, but the best citizens. Calls rang out to publicise and humiliate the names of dissenters. Their addresses made known. Their families, harassed. Homes were vandalised, if they did not, at the very least, fly the now clearly Federal American flag. Some did not, and paid heavy prices.

The draft in this country is not new, and this was a weapon used by the Federal Government against her people tantamount to extortion. Maine’s government preferred honey to vinegar, and conscription came with a fat asterix. Those who volunteered before being force conscripted would receive a bounty. This was an enticement many couldn’t afford, and likely prompted the majority of assents to service rather than media hype and jingoism. If a man could, he could pay a fee of $300 USD to hire a substitute. Very Mephistophelean, if you ask me. However, this arrangement was made so that the theoretically vital could continue to serve the community as needed, and the Fed could eat his fill of blood. Of course, the sorts that substitution theoretically favoured (tradesmen, farmers, landsmen) could rarely afford them. It served only to perpetuate a tenuous divide between rich and poor, and lent much credence to the cause of the Maine Democrats who were growing, not shrinking.

There were harsh penalties for draft-dodging. Some of which hit men where it hurt – their wallets. Corporal punishment was not unheard of. This led many men to “skedaddle” or flee the country. Fun fact, in my part of Maine, the word skedaddle is still very much entrenched in the local lexicon. It now simply means “get out of dodge.” Many such men fled to Canada to join the seldom discussed diaspora of previously transplanted Colonial Loyalists and non-combatants from the War of 1812 – conscientious objectors and such, and, truth be told, those who came to regret having sided with the Revolutionaries. Of whose calibre there had been many, those treated roughly by the first Patriots harboured grievances which they sought to rectify. And so it goes. Not everyone went to Canada. Some men had too much to lose, and so resorted to ludicrous measures of self-mutilation. One man had a dentist smash his teeth, another played home-ec and sawed off a trigger finger. In all cases, they were coolly reminded by Big Fed how their newfound disabilities didn’t necessarily bar them from service. Loaders didn’t need trigger fingers and cavalrymen didn’t need teeth. And the beat goes on.

It is worth noting that even the diehard Republicans could not maintain their façade of plastic patriotism forever. As the nine month promise lingered into a year, and up, questions were asked. What is it all worth? What glories had the war managed, that were equal to the suffering? Men permanently disabled, lost in action. The suffering of wives, of whom some starved without their husbands? What of the children now fatherless? What victories equaled these pities? This strengthened the Maine Democrats’ cause, and in the voting booths, Republicans found themselves victorious by ever slimmer margins until they were nearly equal. Moreover, a curious reactionary bounceback between caution and arrogance led to a string of humiliating defeats for Maine generals in the war. Their resultant loss of life staggered even the staunchest supporter of fratricide.

To make matters worse, because skedaddling had become a fashionable pastime, the Federal Government built concentration camps to store the conscripted in until their terms of service. These camps elicited extreme fury among both supporters and dissidents of the war. The critique was predictable, and not unjustified. To fight a war to free the blacks, free White men were thrown in chains – literally. As government excess continued, the group of people always worth mentioning – neutral parties – began to show their stripes. Many doctors began aiding and abetting in the great skedaddle. So did some lawyers and other tradesmen. Threats of extreme backlash proceeded their every lent aid, but it did not sway the dissident movement.

At a point where Maine’s pro-establishment media began to lament, the war finally came to a close. Rather than quietly put it behind them, the pro-establishment types celebrated Union victory with mass violence. Dissenters were lynched for having doubted, and forced to rehang the flag. Indeed, some had surely commented, the Union had won – but it had also proven the point of the dissenters, which was that the war, indeed maybe any war, had never been about this, or that – but power. Pure, naked power. It had always been a struggle for the Federal Government to establish absolute monopoly over the people. In the poignant arguments between a hypothetical Locke and Hobbes, there was no doubt who Calvin predestined to rule.

It is curious that there was this sentiment that slavery did not benefit the South but for a few select oligarchic monopoly families. Research in the current Dissident Right has turned up validations of this claim, suggesting that many of the initial slaveholders of the South had, in fact, been Jewish. Indeed, one wonders if an enterprising Southern Nationalist might have insight as to whether there was a comparable anti-war sentiment of such Southerners as who did not benefit from the trade. We know from Albion’s Seed, that the South, as a rule, did not receive in equal portions beneficiary outlets from the slave trade and that in fact many Whites suffered for it because they could not keep up with the labour. Again, all too familiar a sound in a world whose government imports coloureds for pure capital gain and uses them as a bargaining chip to dysregulate our economic systems with unnatural labour inflation. At any rate, both North and South had power structures with deleterious influences and neither can truly lay claim to a more Perfect Union – for there was none.

In the event this is what gets me banjaxed off WordPress, tell my mother I said something inappropriately clever. And that Uncle A can have my stereo. Don’t touch my big beautiful weight plates when I’m gone.

Finally, a penny for your thoughts:

Seax is a father, craftsman and Nationalist, as well as a dyed in the wool Yankee. He specialises in esoterica ranging from Teutonic religion to New England history, with a keen interest in understanding, mobilising and rectifying America’s regional identities. He can be found trying to rally the clans in Maine – wish him luck.

Interesting essay, but, WAY. TOO. LONG! We don’t get extra credit for our “much speaking” here, if you know what I mean.

I’ve actually written over-long essays like this before; my rule of thumb when I do is to break them down into thirds – in this case, parts I, II & III. Very few of us – me included – have time to sit down and read 6,200+ word essays in one sitting; I actually quit on this one about 4,000 words in – I had to finish it when I got home from work. After which I took time to do a word count, which is of course where I came up with the 6,200+ figure.

I don’t know how y’all in Maine take to constuctive criticism as such (hopefully better than Bostonians and damn Yankees, et al), but that is all my comment is when you boil it all down – keep the word count down to 2,500 words max, and I for one (can’t speak for anyone else) will be a lot more likely to read your essays in full, and to get from them what you presumably intend to be gotten from them. In this case most of what I got was … “this dude yaps too much.”

All’s fair in love and war, I understand. Thanks for the advice!