These calamitous days have me pondering the parallels between us soft and selfish moderns and the tenacious Southerners who lived through the War of Northern Aggression. What were their hardships really like? Would we be able to withstand even one day of what Confederates (both military and noncombatants) were subjected? Are our battles the same? And what lessons can we learn from their struggles?

So, my history-buff sons and I read “Southern Grit: Sensing the Siege at Petersburg” by Michael Martin, who specializes in what is known as “sensory history.” This is an emerging field which delves into “what was in the mind” of its subjects and “what they sensed.” At just 60 pages, it’s a pithy, power-punch of a book published by the good folks at Shotwell.

Martin, a teacher by trade, had always been enamored with the War, but had received the typical miseducation, leading him to believe that “the South was something of a cultural wasteland.” But his curiosity got piqued when he began delving into his own ancestral heritage and reading the most primary sources of all: the letters and notes of Southerners actually living at the time, most notably, Martin’s 4th grandfather, Younger Longest.

“Discovering Younger’s letters, from a time when many men were illiterate, confirmed my life’s work as a historian and a writer,” he says. “I truly believe that somehow he planted the seeds that would make me interested in history.”

“Eventually, I realized that the South was a lot more distinctive and intellectual than I had been led to believe,” explains Martin, whose years of research and the truths it unearthed made him “wonder if maybe the Southern side of things had been left out for a reason. Maybe the government does not want us to know what Confederates were fighting for.”

“My ancestors showed me … that the American people had a lot of grit compared to the average person today,” he continues. “The bravery and fortitude with which they faced a larger and better equipped opponent deserves closer attention.” Indeed, moderns should take note.

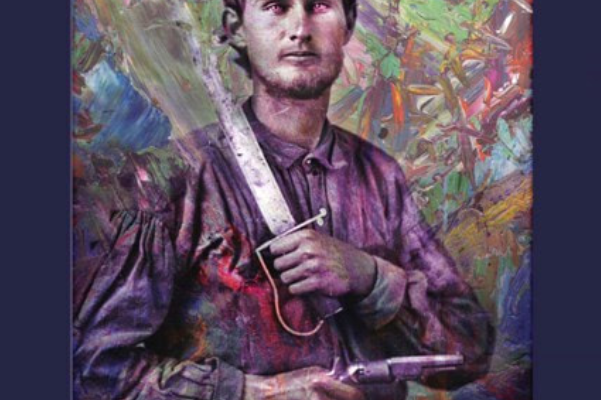

In our culture-Marxist society, Southerners both then and now are ceaselessly ridiculed, marginalized, and dehumanized, but through Martin’s research, we can see that Younger was a simple, but smart hard-working man who simply loved his home. He was an overseer before the War and then served in the 26th Virginia Regiment – a volunteer outfit, meaning that that the soldiers “were at first armed with their own weapons, mainly flintlock muskets.”

We learn more about Younger through people related to the 26th, such as VMI-educated teacher James Calvin Councill, who is written about in the letters of his student Fred Fleet, another 26th comrade. In one, Fleet cites Councill’s leadership in rallying Virginia patriots after Union troops from the 6th Massachusetts tried to travel to DC via Baltimore, where they were “met by a mob of 10,000 people. Shots were fired. 12 citizens were killed and many wounded and 4 soldiers killed.”

Could you imagine a critical mass of people today rallying in defense of their homes and neighbors in such an intrepid and unapologetic manner? I can’t. Even without the community-killing subterfuge of unchecked immigration and multiculturalism, I still think most moderns would either cower or cave. “C’mon on in, boys!” they’d say, while waving Old Glory. “We’ll help you squash those racist neo-Nazis ourselves,” the Karens would screech.

Younger served in what was known as the “Jackson Grays,” Company I of the 26th, named after James W. Jackson. So, who was this Jackson guy and why does he matter to Younger’s story? Or to our story?

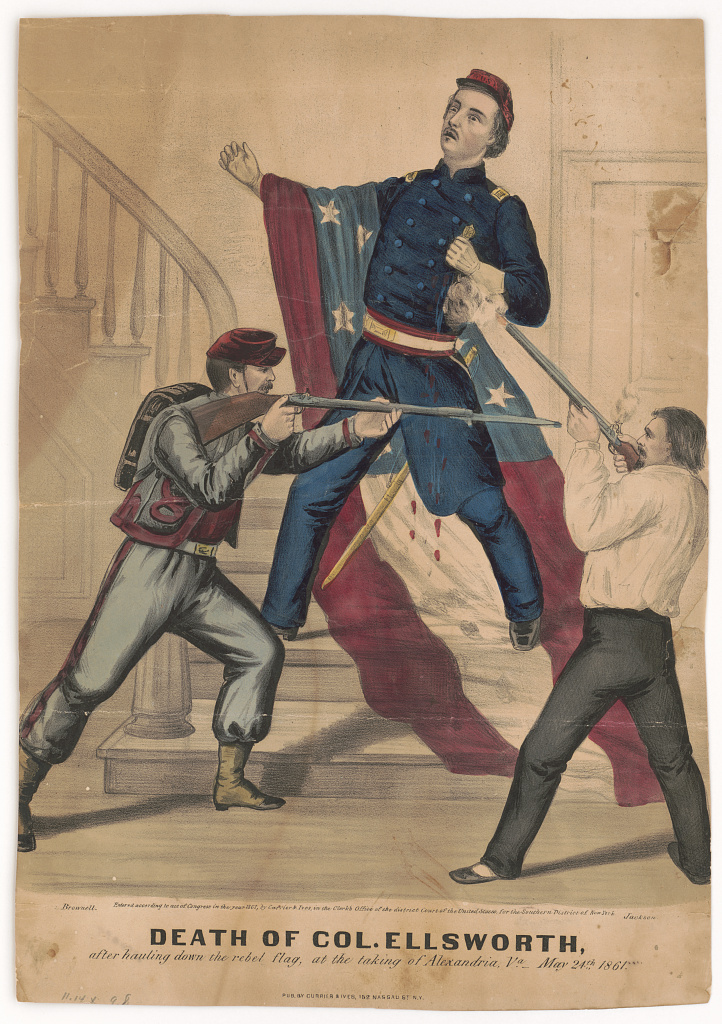

Well, in May 1861, Virginia had just seceded and Federal troops were moving to occupy the city of Alexandria. There, in the now-uber-liberal, Dixie-cleansed suburban Washington city, once flew a First National Confederate flag from atop a 40-foot pole of Jackson’s home and business, the Marshall House. Back then, this symbol of the “tutelary protection of cherished rights” mattered to a great many people, while today it’s an easy virtue-signal to castigate. And rights? Well, those are just the diversionary tactics of white supremacists, don’t ya know?

In typical puritanical-progressive form, U.S. Col. Elmer Ellsworth stole Jackson’s flag as a prize for he and his men taking the city while its citizens slept. As the thieves and intruders celebrated within Jackson’s home, the ardent secessionist met them, shooting Ellsworth “once in the chest with a double-barrel shotgun.” A Union soldier then returned fire, hitting Jackson in the head and then stabbing him with a bayonet.

“At that time, most Southerners would have preferred to die on their feet, atop their violated soil, rather than submit to Yankee terror and invasion,” Martin comments. But would modern Southerners be so bold? I think not. Most don’t fly or bother even defending the flag, much less safeguard their private property with such fearlessness and conviction. So will they submit to forced vaccinations, quarantine-mandated removal from their homes, and other government-overreach schemes? We shall see.

Turns out, Councill, who had established Company I, chose the Jackson Grays name in honor of “The First Martyr for the Cause of Southern Independence.” By putting himself “in Younger Longest’s shoes,” Martin senses that his ancestor and his compatriots considered the flag a “symbol of separation from the United States,” Jackson a heroic resistor to subjugation, and the Dixie cause an honorable one.

But the most compelling part of the book is Martin’s retelling of the nine-and-a-half-month Siege of Petersburg. It’s not just a sensory history of the lengthy military attacks, the brutal trench warfare, and the famous Battle of the Crater, but it’s also a glimpse into the horrors faced by Petersburg’s “women, children, and old men” at the hands of the general government.

“A once bustling hub for the railroad industry, Petersburg was the last stronghold between the Union army and the Confederate capital of Richmond and the place that protected the railroads that supplied the Confederate army,” Martin writes. “To truly break the hearts and minds of Southerners, Federals like William T. Sherman were engaged in ‘total war’ by destroying Southern civilians’ means of living.”

This meant the cutting off of city food supplies, as well as the constant shelling of civilians, their homes, businesses, and churches, and the extermination of life and liberty in this once-thriving Virginia city. The Yankees’ attrition warfarism began in Petersburg on June 16, 1864 and would continue on for the duration of the siege, and is something we can hardly contemplate. Yet, the people of Petersburg sustained and circumvented Union onslaught as best as possible and even had “starvation parties” in order to keep “morale high” during the seemingly endless days of tyrannical torment.

“The grit and unyielding courage [civilians] sustained in the face of hardship is something ALL Americans can and should be proud of,” Martin says of the 18,266 residents including “3,164 free blacks and 5,680 slaves.” Could we moderns, who think abundance, prosperity, and safety are God-given rights, have the mettle to withstand one hour (much less one day or one month) of what the people of Petersburg endured for nearly 10 months? I doubt it.

And what about the soldiers’ sacrifice? In the first battle fought June 15-18, 1864, “the 26th lost companies A, B, and G … [and] Younger and the rest of the regiment remained in the trenches” until March of the next year. His brother was killed in the trenches in early July and his cousin met the same fate in December. Still, Younger fought on.

Younger survived the shocking Battle of the Crater on July 30, the 8,000 pounds of gunpowder mined below the Confederates and lit ablaze by Yankee tyrants, the smell of the corpses of Union soldiers who lay rotting within the blasted-out earth, the fear of being blown to bits from above and below, unimaginable exhaustion, the harsh Virginia heat and cold, the muddy trenches, and the lacking of basic necessities like shoes and soap. Still, he clung to hope.

“Southerners were willing to face a larger, better-equipped force … their resolve and grit are truly remarkable even today,” remarks Martin, who speaks of the “enemy image,” how powerful is this fluid American dogma, and how “terrorism” is always being redefined to meet the needs of the oligarchs.

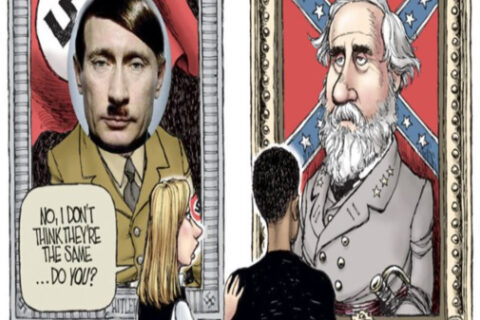

Yesterday, it was the 9/11 hijackers, but today it’s “right wingers,” “neo-Nazis,” “neo-Confederates,” and now anti-vaxxers and reopen activists. If Lincoln said Confederates were “rebels,” why not you and me?

By looking at both history and current events through his “ancestor’s lens,” Martin hopes to “give humanity to these ‘rebels’ that many people only associate with ‘white supremacy.’” Anyone who opposes government meddling in our lives at any level should be sympathetic to this goal.

“The truth is that people … are finally beginning to realize that the government we were left with after the ‘Civil War’ might not be so great after all,” Martin assesses of the regime. If you stand for self-determination, you are the enemy.

“As a nation, we may never again see our own people take arms over governmental principles … [but] it was something Confederates were willing to do,” Martin writes. Would we be willing to stand firm? Do we have a line in the sand as did our forefathers?

“I believe that our ‘Civil War’ ancestors had thoughts and experiences that are still reverberating all around us,” he continues. Younger “may have been guiding me this whole time to find the story he left behind.”

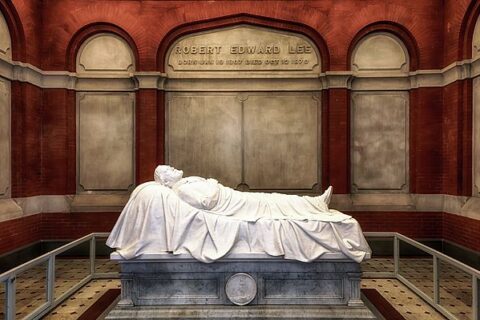

My highest-ranking Confederate ancestor was General A.P. Hill, who was killed in Petersburg on April 2, 1865, the same day “Lee’s army left the Petersburg trenches and headed west.” Just six days later, Younger and the tattered remnants of the 26th reached Appomattox, “just one day before Lee’s surrender.”

Imagine having made it for so long and through so many bloody battles as did Hill, like First and Second Manassas, Cedar Mountain, Sharpsburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and Cold Harbor, only to perish during the final days of the War waged in protection of your home and family. I have read that Hill had once said he didn’t wish to survive the fall of Richmond. So perhaps it was destiny.

But what is our destiny? Just as the Siege of Petersburg was a “battle for the very minds” of Southern soldiers and civilians, we have the same battles today: cultural degradation, the erasure of history, the subsidized miseducation of citizens, the maligning of dissidents, the neoliberal rebranding of symbols, coerced secularization, and the perpetuation of unquestioning allegiance to the central authority. It’s still industrial capitalism vs. human-scale markets, urban vs. rural, authentic collectives vs. centralized technocracy, and agrarianism vs. government-controlled land use and food production. In other words, outsiders forcing their worldview on us through blood, fire, and reconstruction.

Will we fight like our kin? Do people even understand what we’re fighting for and who are the belligerents? Will we lose? Have we already lost?

Dishonest Abe once said that “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” But America’s “house” is anything but sturdy and strong; that is more evident now than ever.

A thousand years ago, St. Symeon the New Theologian wrote, “The roof of any house stands upon the foundations and the rest of the structure. The foundations themselves are laid in order to carry the roof. This is both useful and necessary, for the roof cannot stand without the foundations and the foundations are absolutely useless without the roof.” What are our foundations? Do we even have a roof anymore? Have we ever?

“In the same way the grace of God is preserved by the practice of the commandments, and the observance of these commandments is laid down like foundations through the gift of God,” St. Symeon continued. “The grace of the Spirit cannot remain with us without the practice of the commandments, but the practice of the commandments is of no help or advantage to us without the grace of God.”

Only such firm undergirding can build a durable house. But as Younger wrote, “if it not be God’s will we must be resigned to whatever He think best and let us all try and prepare ourselves to meet Him in peace and where there will be no more war and parting will be no more.” So let’s muster up some Southern grit and pray for God’s grace. We still have families and a faith worth fighting for.

“Southern Grit: Sensing the Siege at Petersburg,” by Michael Martin, Shotwell Publishing, 2018.

Article originally published on May 11, 2020, at DissidentMama.net.

Truth warrior, Jesus follower, wife, and boymom. Apologetics practitioner for Orthodox Christianity, the Southern tradition, homeschooling, and freedom. Recovering feminist-socialist-atheist, graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and retired mainstream journalist turned domesticated belle and rabble-rousing rhetorician. You can read her blog at Dissident Mama.