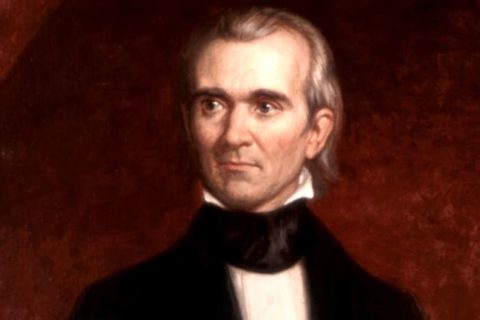

A conservative’s task in society is “to preserve a particular people, living in a particular place during a particular time.”

Jack Hunter, in a review of this writer’s new book, “Suicide of a Superpower: Will America Survive to 2025?” thus summarizes Russell Kirk‘s view of the duty of the conservative to his country.

Kirk, the traditionalist, though not so famous as some of his contemporaries at National Review, is now emerging as perhaps the greatest of that first generation of post-World War II conservatives — in the endurance of his thought.

Richard Nixon believed that. Forty years ago, he asked this writer to contact Dr. Kirk and invite him to the White House for an afternoon of talk. No other conservative would do, said the president.

Kirk’s rendering of the conservative responsibility invites a question. Has the right, despite its many victories, failed? For, in what we believe and how we behave, we are not the people we used to be.

Perhaps. But then, we didn’t start the fire.

Second-generation conservatives, Middle Americans who grew up in mid-century, were engulfed by a set of revolutions that turned their country upside down and from which there is no going home again.

First was a civil rights revolution, which began with the freedom riders and March on Washington of August 1963 and ended tragically and terribly with the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.

That revolution produced the civil rights and voting rights acts, but was attended by the long, hot summers of the ’60s — days-long riots in Harlem in 1964, Watts in 1965, Detroit and Newark in 1967, and a hundred other cities and Washington, D.C., in 1968 that tore the nation apart.

Crucially, the initial demands — an end to segregation and equality of opportunity — gave way to demands for an equality of condition and equality of results through affirmative action, race-based preferences in hiring and admissions, and a progressive income tax. Reparations for slavery are now on the table.

In response to this revolution, LBJ, after the rout of Barry Goldwater, exploited his huge congressional majorities to launch a governmental revolution, fastening on the nation a vast array of social programs that now threaten to bankrupt the republic, even as they have created a vast new class of permanent federal dependents.

The next revolution began at teach-ins to protest involvement in Vietnam, but climaxed with half a million marchers around the White House carrying Viet Cong flags, waving placards with America spelled “Amerika” and chanting, “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh — the NLF is going to win.”

Well, the NLF didn’t win. It was crushed in the Tet Offensive. But the North Vietnamese invasion of 1975 did. Result: a million boat people in the South China Sea, a holocaust in Cambodia and poisoned American politics for decades after that American defeat.

By the time Vietnam ended, many in the antiwar movement had become anti-American and come to regard her role in history not as great and glorious but as an endless catalogue of crimes, from slavery to imperialism to genocide against the Native Americans.

The fourth revolution was social — a rejection by millions of young of the moral code by which their parents sought to live.

This produced demands for legalized drugs, condoms for school kids, a right to terminate pregnancies with subsidized abortions and the right of homosexuals to marry.

The first political success of the integrated revolutions came with capture of the Democratic Party in 1972, though Sen. George McGovern was crushed by Nixon in a 49-state landslide.

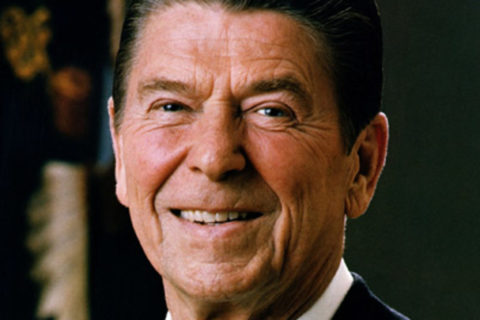

The conservative triumph of the half-century was surely the election of Ronald Reagan, who revived America’s spirit, restored her prosperity and presided over her peaceful Cold War victory. Yet even Reagan failed to curtail an ever-expanding federal government.

Did then the conservatives fail?

In defense of the right, it needs be said. They were no more capable of preventing these revolutionary changes in how people think and believe about God and man, right and wrong, good and evil, than were the French of the Vendee to turn back the revolution of 1789.

Converting a people to new ways of thinking about fundamental truths is beyond the realm of politics and requires a John Wesley or a St. Paul.

The social, political and moral revolutions of the 1960s have changed America irretrievably. And they have put down roots and converted a vast slice of the nation.

In order to love one’s country, said Edmund Burke, one’s country ought to be lovely. Is it still? Reid Buckley, brother of Bill, replies, “I am obliged to make a public declaration that I cannot love my country. … We are Vile.”

And so what is the conservative’s role in an America many believe has not only lost its way but seems to be losing its mind?

What is it now that conservatives must conserve?

-By Pat Buchanan