Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 5:10 KJV

Regarding Southern States during Reconstruction, Mississippi and South Carolina stand out as having the worst inimical abuse at the behest of the Radical regime, yet they are not alone in this suffering. One other state in the Deep South experienced such levels of oppression and chaos as did those two, despite its financial infrastructure still largely intact. Vast ghastly swamps, deadly wildlife, piercing heat and oppressive humidity, annual outbreaks of yellow fever and malaria, and an ethno-cultural divide between its Anglophone North and Francophone South would instill this particular area with an identity not seen in any other. Its greatest city, containing a populace of ornery, free-spirited French aristocrats, Negroes, a few surviving Houma Indians in the rural areas, Spanish Isleños from the Canary Islands, Creoles of color, freedmen, a sizeable plethora of European immigrants from a multitude of different backgrounds, and a robust network of Sugar Planters in the surrounding parishes, would produce one of the fiercest and finest units the Confederacy ever fielded: the Louisiana Tigers. With the Mississippi River comprising the Confederacy’s financial backbone, New Orleans was its heart; therefore, the fetid region presented to the North the crown jewel on the prize of Southern subjugation. With an early beginning to its Reconstruction and rebellious nature of its inhabitants, the Radicals allowed for the most abhorrent of situations to unfold among its inhabitants. This essay seeks to detail the economic, political, and social ramifications and events of Reconstruction which transpired in Louisiana.

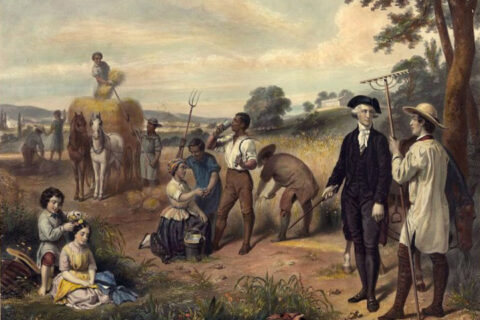

Economically speaking, the vicissitudes which caused the financial collapse of the Southern monetary section occurred differently in Louisiana. The Francophillic, multi-ethnic culture of New Orleans, its lack of destruction and early occupation during the War Between the States, and reliance on sugar, instead of cotton, as a cash crop flowed directly into the state’s position upon ceasing of hostilities. While the plantation system did not fare well upon military invasion, New Orleans’ infrastructure and population remained relatively intact, but the latter did experience a reasonable decline in White males as a result of warfare and recruitment. The Union Army occupied the great port city early in the War, and it only occupied it, favoring suppression and thievery over outright scorched-earth razing as it did in other Confederate sections.

Its Planter aristocrats and urban infrastructure still intact, southeast Louisiana, the heart of the state’s economy and home to Dixie’s largest city, appeared to hold a significant advantage over adjacent states. Unfortunately for it, federal military occupation and mass population displacement prevented such an advantage from achieving fruition.

The aforementioned sugar plantation economy and financial power of New Orleans directly influenced the political machinations of Radicals. Being a port city and the largest city within the Confederacy, Union forces seized New Orleans in 1862, early in the War. Therefore, Louisiana’s Reconstruction began in 1862. It is of no accident the federal Republicans quickly closed in on seizing the city. Unfortunately for the Pelican State, its grapple with Reconstruction under the Federal boot heel would be the longest of the former Confederacy, as well as, one of the most reprehensible and violent.

As the Radical Carpetbagger regime controlled the state between 1867 and 1877, the economy sank deeper into hopeless destitution. During this time, the state legislature spent unscrupulously, granting numerous bonds to railroad and levee companies which did not hold up to their end of the bargain, gave themselves raises, and issued bonds on bribes from numerous manufacturers and services. Businesses simply did not thrive and often shut down, young men left the state in droves due in search of work, plantations produced little during seasons of good weather due to the insolence of Negro laborers who simply refused to work and often stole the crops for themselves, and the general population lost hope. Adding insult to injury, taxes were set at an impossibly high rate relative to the available work and monetary situation of the propertied Whites. Between 1871 and 1874, 491 seizures of property took place in New Orleans alone. By the 1870’s, Governor Kellogg realized the state could not even pay so much as the interest on its debt. He encouraged the General Assembly to cut spending and manage taxes more efficiently but to no avail. The economic situation in Louisiana was so utterly downtrodden and hopeless that even the great port city of New Orleans no longer received immigrants. Throughout the entirety of this series of affairs, politicians not once brought about any signs of recovery, seeking only to leech from the White people of the state and sewing such frustration among the populace so as to catalyze an unremitting series of racial conflict and strife.

General Benjamin Franklin Butler catalyzed Louisiana’s Reconstruction. He led the Union contingent which captured New Orleans in 1862 and administered it and the surrounding parishes from May to December of the same year. Adhering to a malicious anti-Southern administration, Butler utilized the federally enacted Confiscation Acts to their fullest extent and beyond. Seizing as much property from loyal Confederates and slaveholders, many of whom were men off valiantly fighting for their home, as well as swathes of available cotton without compensation, Butler’s forces ransacked Nola, stealing anything of value not bolted down. Negroes flocked to the cities and towns en masse, to such an extent the Federal forces could not maintain the cities’ infrastructures. Butler would often utilize this vagrant population of Negroes as a recruitment pool, sending them into rural areas to free slaves and conduct patrols. This latter act would be to the chagrin of some of Butler’s officers, who justifiably believed this would simply cause further unrest and distrust among the Caucasian populace.

Nevertheless, these laws would not define his most grievous of crimes. His General Order No. 28, the very wartime law which solidified him as a local villain in the annals of Louisiana history, addressed and combatted the most ardent opponents of Union occupation. Women notoriously held Federal soldiers in utter contempt, doing everything in their power to abstain from any such notions of Southern Hospitality when publicly and privately dealing with the invaders. Butler’s order gave soldiers the permission to treat an offender as “a woman of the town plying her avocation.” Simply stated, this demoted these women to the status of prostitute, lacking any privileges of chivalry, and the soldiers could physically and verbally rebut these women as they pleased, often to the point of unjustified abuse. Locals despised this act of cruelty to such a degree that Butler’s name would continue to be cursed well into the 21st Century. Lincoln would later remove Butler in December of 1862 after a few controversial mishaps in regards to political affairs with Lincoln and the North.

Following Butler’s removal, few statesmen of discussion deserve mentioning, military or civilian. Nonetheless, one man did stand out above the rest between 1865 and 1867. This man was Governor James Madison Wells. A grifter through and through, Wells won the governorship in 1865 and set about bestowing upon as many former Confederates suffrage as possible within his power, but his tenure was not such a positive moment within Reconstruction. Radicals attempted to reconvene a rump constitutional convention while employing the same delegates as the convention of 1864. This resulted in the New Orleans Race Riot of 1864. This event and the Black Codes, milder in Louisiana than in other Deep South states, were utilized relentlessly by Northern Radicals. Additionally, Wells would endorsed the ratification of the 14th amendment. The native Louisianans balked at this proposal. Not a single well known or respected man of reputable stature opposed the amendment, including Confederate General James Longstreet. The Southerners knew of no one else to turn to, yet they knew little of what laid over the horizon.

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 catapulted the state into the harrowing depths of wholesale Radical control. General Sheridan, the appointed commander of the Fifth Military District, removed Wells due to the latter’s lack of action in preventing widespread unrest. A new constitutional convention was held in 1868 and a new governor elected with an overwhelmingly Republican general assembly. Governor Henry Clay Warmoth was arguably the most pivotal figure in all of Louisiana’s Reconstruction. Consolidating an asinine amount of power under his belt, including delegation of numerous parish positions and militia control, Warmoth initially appeared as friendly to Radical legislation. The exceptional incompetence and frivolous spending of the General Assembly drove Warmoth more into a position of moderation. This move would quickly alienate him from Negroes and Radicals, forming a violent rift within the Louisiana Republican Party. During the gubernatorial election of 1872, Warmoth endorsed the Democrat candidate John McEnery against Republican William Pitt Kellogg. The election would remain contested until 1874, and Warmoth vacated his office under threat of impeachment 35 days before the end of his term.

A dual government unfolded with neither candidate conceding defeat. The Warmoth appointed returning board declared McEnery the victor, but the Republicans contested this with calls of voter fraud. In 1874, President Grant declared Kellogg the victor. Kellogg’s tenure merely continued the sheer absurdity of the Radical Republicans of the Warmoth administration. Like his predecessor, Kellogg called for economic restraint, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. He accomplished little, and his administration’s most notable characteristic was presiding over the rebirth of wanton violence throughout the state, including the attempted insurrections known as the Battle of Jackson Square and the Battle of Liberty Place.

Louisiana’s political overthrow of Reconstruction during the election of 1876 amounted to revolutionary heights. Republicans chose the unremarkable Stephen Packard for their nominee. Contrastingly, the Democrats, renewed with a vigor not seen since 1860, chose the honorable Confederate General Francis Redding Tillou Nicholls. A Louisiana native, Nicholls served honorably as an officer under Stonewall Jackson, losing an arm and a leg during the War Between the States, and the Democrats could not have chosen a better man to Redeem Louisiana. Campaigning with everything in their arsenals, the parties generated such interest in the election that the election drew national interest, alongside the South Carolina election of the same year and the Mississippi election of the previous year, exemplifying the final gasp of Reconstruction. So interesting was the affair and so intolerable the poverty that old-line Whigs, disillusioned Bourbons, and vehement racialists voted alongside each other in support of Nicholls. The spirit of Louisiana was reborn, determined to seize its rightful control of the state.

Then election day came and went peacefully, despite all of the rigorous campaigning and tensions high. Regardless of the returning board’s counting, claims made by both parties, and accusations of fraud leveled at both sides, a winner was undecided. President Grant refused to rule on the matter. Packard’s Republicans barricaded themselves in the state house under the protection of the federal troops stationed in New Orleans. Meanwhile, Nicholls was paraded through New Orleans to uproarious applause from the masses of Democratic supporters. Parishes slowly began acknowledging his governorship, and Packard had little reach outside of the state house. Finally, Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes, in a bargain to settle the disputed presidential election of 1876, enacted the Compromise of 1877, declaring Nicholls the victor in Louisiana and Democrat Wade Hampton III the gubernatorial victor in South Carolina in addition to withdrawing the remaining troops from Dixie, all in exchange for those states’ electoral votes. Redemption finally came to Louisiana, bringing a time of soul crushing turmoil to a close and allowing the institution of respectable government for the first time since 1860.

Though not the most ardent of secessionist states to originally secede from the Union, the people of Louisiana produced arguably the most belligerently anti-Radical sentiments among Southerners, even in the Deep South. Occupied by 1862, New Orleans’ Whiggish, multiethnic population lived oppressed and in close proximity to invaders though lacking the traditional, scorched-earth negativities of invasion, and the remaining rural counties were mostly secessionist Anglo-Celtics. This difference in ethno-cultural foundation imposed little effect on the loathsome attitude the average Louisianan held for Radicals and kowtowing to Negros, a resolve which only strengthened with time. Invasion, General Butler’s plundering of properties, being stripped of the franchise only to have it returned and then stripped again, inversion of the social hierarchy, unremitting demonization at the hands of carpetbagging Radicals, unjustifiable hostility of Negroes due to Republicans seditious rhetoric, the Reconstruction Acts, and fervent, rabid insanity of Republican rule proved too much for the White population to peaceably abide.

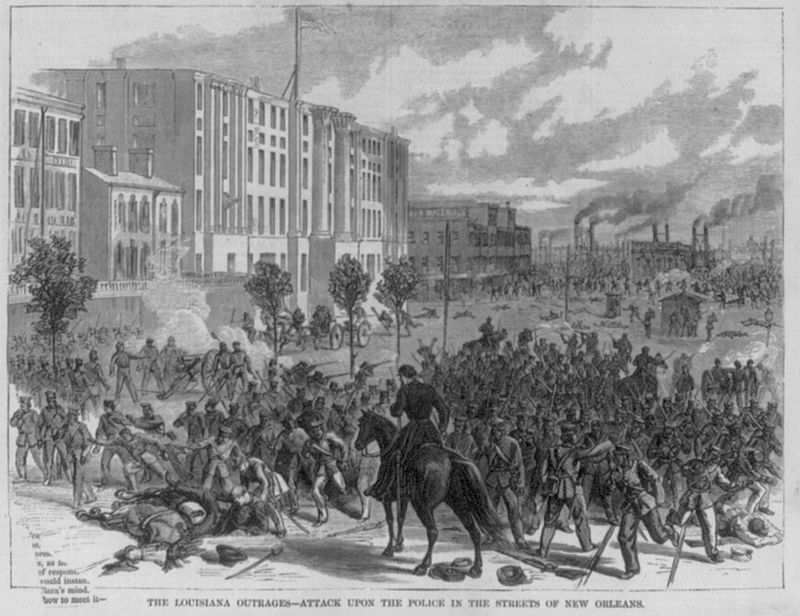

Louisianans steeled themselves in their recalcitrance following the passage of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. These tyrannical pieces of legislation would hurtle the state into a period of bloodletting so distant from the contemporary individual that any attempt to imagine the situation could only be described as an arduous affair. Beginning with the New Orleans Riot of 1866, violence in the state would increase with effervescent brutality and take on an unwavering ferocity and coordination as time continued.

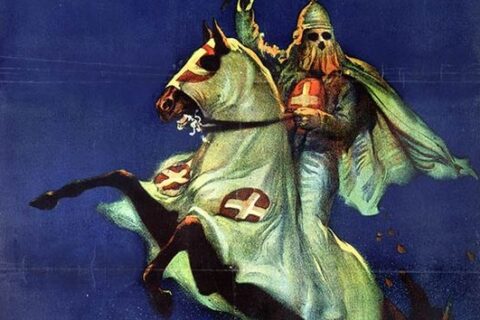

A plethora of militia and resistance groups organized, with two differing waves distinguishing them. The first wave lasted from 1865 to 1871. This initial resistance to Reconstruction carried with it the most separate organizations. The groups to form in Louisiana were numerous and included the Seymour Tigers, Swamp Fox Rangers, Seymour Infantas, and The Innocents. The Ku Klux Klan did exist in a handful of rural parishes, but that particular organization held little sway in the state. The largest and most influential organization within Louisiana to form was the Knights of the White Camelia. Founded by Alcibiades DeBlance, the Knights of the White Camelia found popularity primarily among propertied and respectable Whites and preferred political and social influence as opposed to outright violent intimidation, often detesting the actions of the more unhinged and widespread Ku Klux Klan. All of these noted groups operated primarily during 1868 and managed to swing Louisiana in favor of the Democrat candidate Horatio Seymour during that year’s presidential election, one of the only former Confederate States to do so, and they also stood against the Union Leagues and multitude of Republican clubs throughout the state. This spike in organizing also left a trail of blood in its wake. Alongside the savage Opelousas Massacre, various massacres and race riots took place in the parishes of Bossier, St. Landry, St. Bernard, and Orleans. Following 1868, this form of activity would begin slowly declining and disappear altogether by 1871 due to the passage of the Enforcement Acts, bringing an end to this first violent wave.

As the penury and inverted social hierarchy continued to worsen during the 1870’s, the desire for violent resistance found rebirth among Louisianans, emulating the baleful violence of 1868. After 1867, life for Louisiana Whites became lesser than even the lowly slave. Companies of Negro militias freely roved the towns and countryside, being regularly supplied with the most state-of-the-art rifles. Black laborers became impossible to compel to work the fields and leisurely stole from plantations, resulting in poor crop yields. Courts rarely convicted Negroes of crimes, and White women in rural parishes, particularly parishes in which most former Planters lived, seldom left the plantation houses for fear of attack. Deep South Negroes came from slaves sold off from the Upper South due to the slaves’ more ornery behavior and disposition to break rules, resulting in a greater propensity for the Freedmen to exude more unruly behavior and strengthening White misery and fears. Unreasonable taxes, indigence, and no representation whatever only compounded the problem. These social conditions came to a head in 1873.

The contested gubernatorial election of 1872 and the ever present increase in racial tensions finally drove Whites to their breaking point, and the Colfax Massacre of 1873 occurred. Fearful that Democrats would attempt to seize the Grant Parish Courthouse amidst the widespread chaos, Negroes took up arms and barricaded themselves alongside Republican officials in the building. Armed Whites would pour in over the next several days, and the massacre itself would occur. Sparking nationwide outrage, condemnation would not bring an end to the violence. By 1874, the White League would form, organizing throughout the Red River Valley and New Orleans; furthermore, various rifle clubs began organizing so as to patrol rural areas and put an end to the Negroes’ thievery. Not all aspects of this rejuvenated organizing carried with it a positive tone. Birthed in bleak hopelessness, the groups unleashed sanguinary campaigns throughout the state, and the Battle of Liberty Place, a justifiably attempted overthrow of the Kellogg government at the hands of the White League, stood at the apex of this uncontrolled brutality. Yet not giving in, Louisianans continued their fight against Reconstruction, and it fortunately ended in their favor. Only South Carolina and Mississippi would match Louisiana during Reconstruction for the amount of ruthless barbarity.

With the Compromise of 1877, Reconstruction finally drew to a close in Dixieland, allowing for its full Redemption and an age of political sovereignty not even seen in the Antebellum Period. Considering the economic, political, and social hurtles, the Redemption of Louisiana undoubtedly qualified as a total revolution, bringing to end a macabre state of existence for the native population. Afterwards, Louisiana continued as an economic powerhouse and cultural hub within Dixie, and New Orleans stood as the region’s largest city until after World War II. A stalwart segregationist state and producing noteworthy political influences in the regional and federal levels, this multi-ethnic, multilingual backwater with some liberal and populist predispositions produced some of the most superlative, effervescent, and eccentric statemen, which included Governors Huey Long and Jimmie Davis, District Attorney and Judge Leander Perez, State Legislator William Rainach, and Senator Allan Ellender. The Jim Crow Era being its golden age and experiencing steep decline since that period’s end, Louisiana managed to preserve its unique ethno-cultural and linguistic foundation even into the contemporary social sphere. Unfortunately, media, education, and politics see fit to erase the state’s history and rewrite the origins of its unique countenance, New Orleans facing the behest of this modern day Reconstruction. With any luck, a revolution on par with the Compromise of 1877, the best option being secession, would restore Louisiana to its glory as a member of the Deep South, but the odds of this are abysmal at best. Thankfully, Louisiana’s history still exists and is easily accessible to those determined to find and preserve it.

Afterword: After a year and a half of reading and writing, my series on the Dunning School of Historiography on Reconstruction now comes to a close. Beginning in February of 2020, I have covered Reconstruction in every former Confederate State, utilizing the Dunning School’s suppressed library of books and information, so as to preserve the true history of the South during Reconstruction and bring it to our generation of Southern Nationalists. If you should like to read the other essays covering the period, they are all included under the “Reconstruction” tag. With this concluding afterword and entry on Louisiana, I bid the Reconstruction Series an adieu.

“The White people of the South are the greatest minority in this nation. They deserve consideration and understanding instead of the persecution of twisted propaganda.” –Strom Thurmond

Thank you for taking the time to produce these excellent summaries. Going in the homeschooling file.

👌🏻

Thank you for sharing. Louisiana is still suffering from the thieving, shiftless negroes and whites who do nothing but take from her bounty and vote for sorry sons of bitches like John Bell Edwards.

Greatly enjoyed your articles Sir.Thank you.How can I access ones I missed?

https://identitydixie.com/tag/reconstruction/