I recently had a discussion on the merits (or rather demerits) of Industrialism and it sadly seems that the majority of Southerners have abandoned the historic Jeffersonian Agrarianism of their forefathers for Hamiltonian Industrialism. There are many reasons for this, much of it can be connected to the Progressive Movement of the early 1900s and the New Deal, especially. It can also largely be traced to the related idea of the “New South.” Many will opine about how Industrialism has made life easier, including the increase in longevity, healthcare, and ease of chores. Now, I don’t think all progress is bad, but I will say that much of our so-called “progress” has actually done far more harm than good.

To begin, let us define the two main, competing ideologies of the Old Republic. In sum, the Jeffersonian model was the belief in stronger state and local governments, with a significantly weaker national government, free trade, Agrarianism, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. The other major ideology of our founding was Hamiltonianism. Many of Hamilton’s positions were the opposite of Jefferson. Hamiltonianism advocated for a stronger central government, internal improvements, a central bank, protectionism, and an economy based primarily on banking and mercantilism, rather than agrarianism.

While I think the Jeffersonian model is preferable, there have been sensible critiques of his ideology. These criticisms include Jefferson’s tendency towards rationalism, as well as, his friendliness toward radical French Enlightenment thought. Despite these flaws, by and large his ideology remains an overall positive for the American people.

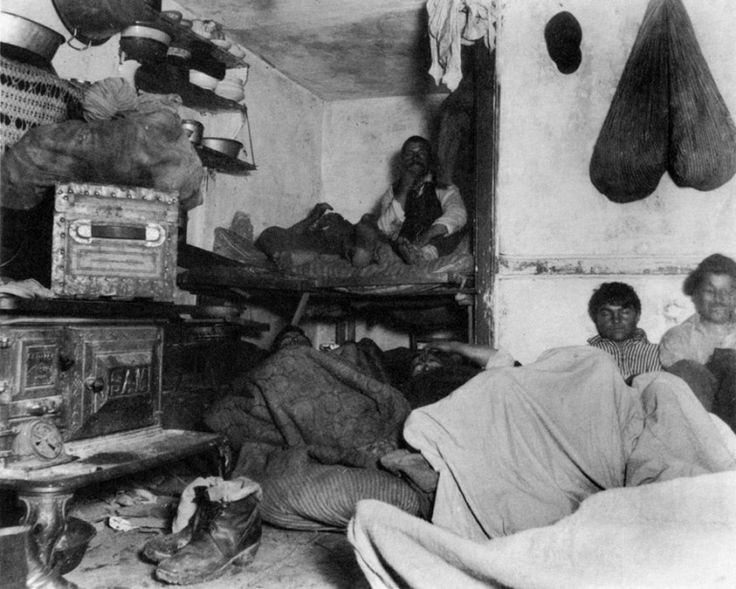

Now, how this relates to Agrarianism versus Industrialism is significant. One of the chief reasons why Jefferson was a proponent of Agrarianism is he rightly saw it as the only form of society that was really compatible with a democratic republic. Only in an agrarian society, with a large class of freeholders, can the people be truly free and independent. The same cannot be said of factory workers living in tenant housing in an urban slum. Industrialism is also problematic to republican government because it tends to create a corporate class that is often able to grow as powerful as the government. This naturally leads to crony capitalism and all sorts of corruption. Finally, Industrialism is unfriendly to limited government in that it, almost by necessity, leads to increased regulations and stale bureaucracies.

So, what happened to the old Jeffersonian America? As U.S. history testifies, it was a slow process that was ultimately destroyed with the emergence of the American Empire after the fall of the Confederacy. Lincoln, as an heir to the Hamiltonian school, represented the triumph of Industrialism (the North) over Agrarianism (the South). The Lincoln Administration provided the death blow to states’ rights and paved the way for corporatism and the transformation of the Old Republic into the American Empire.

The death and decay of old America continued throughout the rest of the 1800s and into the 20th century. This was especially evident in the creation of the Federal Reserve (1914), the Federal Income Tax (1913), and the numerous wars of the Empire, including the Spanish-American War (1898) and World War I (1914). While the majority of Americans were still farmers at this time, and the country still remained predominantly rural, the Northern industrial cities continued to grow in size and power. Fortunately, the South and much of the West remained strongly agrarian until after WWII. But, FDR’s influence would ultimately drive the nail in the coffin of American Agrarianism.

Surprisingly, FDR was quite popular among your 1930s American “normies,” especially the yeoman farmer. The American farmer of that time was hit hard by the Depression and many people had become desperate and disillusioned with the old system. Ultimately, some might argue that Roosevelt was good for the South. Afterall, he bought jobs and helped the South catch up with the rest of the U.S. (to a degree). This was done through various programs such as the TVA. While some jobs may have been created, what really happened was a transformation of a way of life. The changes continued throughout the second half of the 20th century and was exemplified by the idea of the “New South.” This trend has continued into the present day, with a majority of Southerners now living in or near metropolitan cities.

I imagine some are already thinking, “but what about progress?” While it is true that Industrialism has brought us some good, much of this “progress” has been detrimental to our people and our neighbors. The modern industrial economy is a mixed bag, at best. One of society’s greatest advancements has been modern medicine. Because of it, the infant mortality rate is much lower than it was a century ago. The internet, arguably one of the greatest inventions of the modern age, is a little bit different. It’s made life easier to stay in touch with friends and relatives. On the other hand, the internet has also been a scourge to society, for it has made the spread of vices, such as pornography and other forms of immorality, much easier. The internet has also made us less social in our real lives in many ways, for people have become so ensnared with their technological devices that they ignore real life interactions. Furthermore, the internet and smartphones, especially, have severely lowered our attention spans and turned us into dopamine addicts.

I’m not advocating that we, as a people, revert to the Stone Age, but we should be more discerning of what technology is actually an overall good for our people. Some time-saving devices have made life easier, but oftentimes there comes some hindrances to our quality of life. Mechanized agriculture is the perfect example. While it does make things more efficient, it was key in moving people off the farms and into the cities. This happened because less labor was needed to work the farms. It also put a lot of the smaller farms out of business because they couldn’t afford to keep up with the larger mechanized farms.

Much of what I’ve mentioned is why the Amish reject a great deal of modern technology. Contrary to popular belief, they don’t simply shun technology because they hate innovation. Instead, and according to their worldview, they choose to adapt or reject a new technology based on whether it will be an overall harm or positive to their community. For example, many of them consider telephones as an overall negative because it may cause people to simply chat on the phone rather than stopping by for tea or chat face-to-face.

It can also be said that some technology takes the humanity out of work. This is one of the reasons I enjoy old fashioned, hand tool woodworking. There’s just something soothing about using hand planes and chisels that’s lost with the loud power tools. When I use hand tools, I’m more involved with the creation of the piece, whereas when I use power tools I feel that the machine is doing most of the work. This is why many folks like driving manual transmissions.

Don’t get me wrong, I do like table saws because they can save a lot of time if I’m in a rush, and saw mills are great, too. And, returning to an agrarian society doesn’t mean we have to wholesale rid ourselves of power tools and other advancements. Even the Antebellum South had some factories; the caveat was that, in an agrarian society, the cities were based around an agrarian economy. In turn, the city factories would largely produce goods for the rural economy. This would include things like plows, cotton gins, milking equipment, etc.

However, we should examine the claim of prolonged longevity as a virtue of Industrialism. It is true that we now have a lower infant mortality rate and more cures for diseases. I do, however, question if today’s average adult is really healthier and living longer than their forbearers. Just look at the kinds of food people were eating in 1820 versus 2020. The quality of food was almost always better. On top of that, people were much more in shape, and lived a more active lifestyle. If one takes away the number of people who died in infancy/early childhood, as well as, those who died from wars and famine, I don’t think the average lifespan ends up being significantly different. Even David seems to state in Psalms 90:10 that man’s average life expectancy is 70 or 80.

Eric Sloane in The Seasons of America Past states:

“The elderly man of today has less chance of living than did his counterpart of the past! In 1832 a special census was taken of all people in the United States over one hundred years old. The possibility of inaccuracies was taken into consideration and hearsay, such as reports of Negro slaves, was ruled out. It was found that at least one person in ever forty five hundred Americans was one hundred years old or more. Today the figure is only one in thirty four thousand.”

So, according to Sloane there were actually more centenarians in 1832 than his own year of 1958!

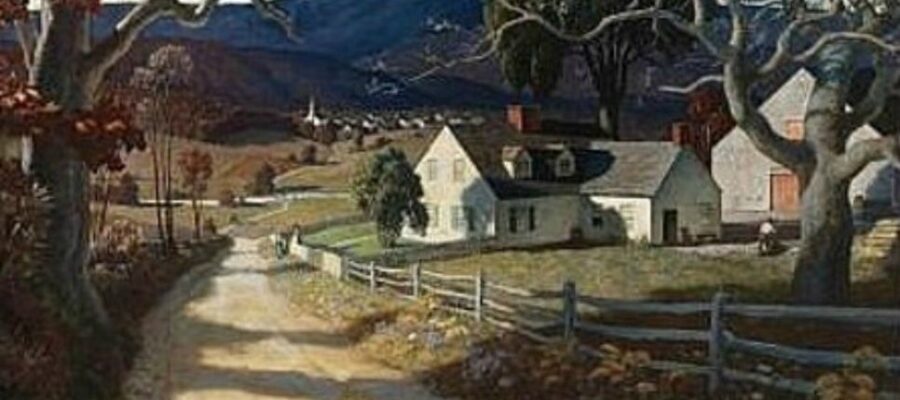

In many ways, people were more healthy spiritually, as well as, community wise. For instance, day care was unnecessary because the family all lived on the same property and the mother didn’t need to commute to a corporate job. The husband worked the land, so he also worked from home. Consequently, he was able to have an active part in the family’s life and fully take on his God given role as patriarch of the family. People oftentimes had more downtime on the farm – especially, during the fall and winter. As a result, people were able to be more involved in community affairs. Families also had more time for family worship and devotion.

Industrialism has been destructive to the Christian family and the community in many ways. One of the results of Industrialism is that children are no longer considered a blessing, but are instead considered a curse. In the old agrarian societies, children were considered a blessing because they provided extra hands to work the land. In contrast to today, children are often seen as a burden people can’t afford in an industrial society.

Industrialism also splits up and fragments families, leading to increased atomization and a loss of familial ties. When one is forced to uproot and constantly move, it becomes harder to remain close to extended family and communal ties. It doesn’t help when one, or both, of the parents have to commute to work, thereby further reducing time with one’s own immediate family. As a result, people have become de facto gypsies who find no use in forging communal ties if they are likely to move again. This leads to a growth in nihilism and social isolation.

Agrarian societies tend to conserve traditional folkways, language, and local culture better than cities. This is very evident today, especially with our large multicultural metropolitan cities. This is easily explainable since small towns tend to be composed of groups of closely related tribes, whereas many of today’s cities are composed of people from all over. As a result, many cities are very cosmopolitan and lack any real defining culture. This is one of the many reasons why cities are hotbeds for radicalism. When people are disconnected from the land and reduced to being a wage slave in some factory, they become susceptible to dangerous ideologies such as communism. This is largely one of the issues the Jeffersonians wanted to avoid. By the 1700s, England was already starting to experience the perils of Industrialism with the loss of farm work and the creation of a large urban peasant class. Jefferson wanted to avoid this and instead create an “Empire of Liberty.”

Another advantage of the old agrarian model is that it’s naturally built on a conservationist model. Due in part to the Left’s radical environmentalism, there has, unfortunately, been a backlash to anything at all having to do with conservationism among the mainstream Right. This is evident among the neoconservatives, a people who pride themselves on urban sprawl, endless development, and the destruction of natural resources. This is an infantile view. As conservatives, we should want to conserve God’s creation. In fact, we are called to be stewards of the Earth, not exploiters. Agrarianism goes hand in hand with conservationism. In order to have a successful farm, one must make sure he doesn’t overharvest the land. In addition, agrarian societies aren’t typically polluters, and much of the material created can be reused (wood, metal parts, manure, food waste, etc). The same can’t be said about our modern industrial society with the endless amount of plastic junk we produce and consume.

While it is unlikely we will return to a 1790s version of pre-industrial America (at least in our lifetime), all hope is not lost. The reform of Clown World will not happen overnight. What we can do is take steps toward improving our communities on a microlevel. Some ways to take back our agrarian past could include simple things, like getting to know your neighbors, planting a garden, having backyard chickens, and weaning ourselves off our technology addiction by becoming technological minimalists.

It’s true that we have more comfortable lives than our ancestors did a century ago, but are we really better off? Yes, we may have Netflix, Cheese-It’s, Xbox, and Mountain Dew, but we have lost the deeper meaning of life. We must help our society realize the importance of being rooted to the soil, and heed the wisdom of our Jeffersonian forebearers, and then maybe we can return to a more healthy and sane society.

-By Dixie Anon

O I’m a good old rebel, now that’s just what I am. For this “fair land of freedom” I do not care at all. I’m glad I fit against it, I only wish we’d won, And I don’t want no pardon for anything I done.

Great post! We are not better off. Care of the soul, and pointing out our ultimate end,heaven, is a joke to the modern. But wasn’t it a joke to Jefferson too? Did Jefferson care for souls of the men of the nation he was influencing? Family and society cohesion may have been easier to accomplish in an agrarian society but without the true religion, how long before things break down?

I am faithfully reading Dom Prosper Gueranger’s Liturgical year. He does not spare heresies one dart or arrow of condemnation. Any deviation from the Faith is vigorously attacked. What is particularly appropriate about Geuranger is he is writing in the modern time, the 1870, and was a friend of Pius IX. So he confront and attacks, with all the pope’s of the 19th century, Liberalism.

The founders including Jefferson were steeped in liberalism and had no interest in any notion of a “true religion”. Like Locke, don’t you think they assumed any vague notion that “Jesus is Lord” was enough for a nation? Did they even bother to include His name in their founding documents? No!

Wasn’t the medieval system of guilds also suspicious of innovation? From a traditional catholic perspective, we alsways look to the 1000 years of a United Christian Europe for a model. Didn’t jefferson and Washington spur Christendom and leapfrog past it to pagan Rome?

I love my country, I love my adopted Land, the South. But we are dealing with serious philosophically flawed systems here. Flaws that can only be cured by the true religion, the Roman Catholic Faith. (Not to be confused with whatever freemasonic/J*wish nonsense that was created in the 1960s and that has overtaken formerly Catholic parishes and chancellorirs…)

Your overall point is spot on. As I’m sure you know, Jefferson also wrote that if and when Americans began to pile themselves on top of one another in big cities, they/we would become as corrupt and spiritually bankrupt as our European cousins and counterparts. That isn’t a direct quote of course, but the spirit of what he said is nevertheless there. Noah Webster (the fellow who wrote the dictionary) was a Yankee – a Connecticut man – who also advised his fellow citizens that ‘our safety is in the country people, who are out of the reach of demagogues.’ Again, not a direct quote, but I’m too lazy at the moment to look it up. Of course modernity and industrialization brought us *all*, to the man, within immediate reach of demagogues.

BTW, if and when you write another article along the same lines, don’t forget to add impersonal state care of the elderly (nursing homes) to your list. There was a time in America – a better time – when families took care of their own elderly. It’s no coincidence either that during those times young married couples had lots of children. The reports of elderly dying in nursing homes of loneliness during this COVID nonsense are of course heart wrenching, but, I mean, what better do we expect?

Good article, sir. Thanks for taking the time to write and to post it.

Your point about the importance of freeholders rings true.

Moving into the future, we Southrons need to integrate high tech with an Agrarian lifestyle. I believe this is entirely possible. The industrial revolution was a centralizing force. We are currently undergoing a new industrial revolution: we are seeing industrial processes simplified and miniaturized.

What this means is that we can have Agrarian communities that are full of new “cottage industry” — small shops providing engineering, computer programming, metal working, wood working, electronics fabrication, etc etc. In this way we can reap many of the benefits of industry while avoiding many of the drawbacks. The foundation, however, must remain our church, our small farms, and our civil society.

The thing that makes me the maddest about industrial society is the loss of the unique character of our cities and towns. Each metropolitan area has the same chain stores and it’s becoming harder and harder for a small business to compete. Even more so now that online shopping has become prevalent. The center of town has been replaced by the strip mall and Amazon. Even the buildings look the same: all monstrous boxy-looking things with lots of glass and metal. Contrast that with the beautiful architecture of our old Southern towns. That’s a whole other topic right there.

After reading this piece, the song “Little Man” by Alan Jackson popped in my head. I think it summarizes the general decline of our Southern communities. I know this applies to my own hometown.

Excellent.

I think though that at best we will be headed to an economic system that uses less fossil fuels as the national economy contracts and fossil fuels become less affordable.

We should be gathering up knowledge of traditional ways of doing things, enhanced by improvements discovered by tinkering and greater knowledge.

You can be agrarian and still use fossil fuels, which will still remain around. True, eventually natural gas will be more useful and prevalent, while maybe nuclear and to a lesser degree the other alts will be around as they carve their space out; but diesel still hasn’t been replaced, and gasoline and still some of the plastics will remain efficient. An independent Dixieland would do well to hold onto the Gulf oil platforms for dear life.

Of course, a lifestyle that tries its best to not pollute nature is ideal otherwise, but some technology and ergo some mineral exploitation will be needed. Not only for defense purposes, Dixieland needn’t be North Korea either. Citizens could have independent and/or decentralized community servers, for example. Brae Jager makes a good point too.

I’d also argue agrarianism works on the societal level for sure, but economically it still hard to eventually give all yeomen land and not run out of it. Jefferson bought half a country of land, of course he was going to succeed at first. That was the problem America faced as the frontier closed, eventually urbanization and agribusiness and the Yankee system won. That was the other flaw of Jefferson, his rationalism and democracy allowed the Yankees and Dixielanders to split up then have one consume the other. Of course, you could argue the Hamiltonians made it all rigged in the first place, but we can regress a lot to be honest…

I don’t think overpopulation is a big deal, however, and perhaps some compromise solution can be reached that would look more like the New South, in which you had perhaps a balanced system of small cities and lots of towns and still some farmers (both yeomen and aristocrats). It would have to be enforced from above to a degree though, due to decentralizing not only power but also communities and economies. Like in medieval times, you might have to forbid living in cities unless born there, while encouraging people to be tied to the land in a real sense – not in today’s fake sense in which you are a credit-slave of the bank, rent-welfare-slave of the government, etc. Either give homesteaders the land (with caveats of course) or have some system of patronage that allows the settler to stay on land while giving parcel to patron (of course, with caveats so abuse happens the least). Stores and businesses will have to be by locals and for locals again, whether banks, movie theaters, stores, etc. Probably the major retailers and banks will merge with government anyway before this happens, but it could be made so they only funnel wholesale to the local economies. Churches and unions will be important again as decentralized local organizing bodies too. It will be hard to impose though, but will happen eventually anyway, as more and more tire of cities.

Re: fossil fuels, if you haven’t read up on peak oil, check it out. As oil is limited, at some point peak oil production will be reached, if we haven’t passed it already, and oil will start to become more expensive relative to what economies, as they contract, can afford. It would be better to start transitioning to local economies, especially farming, that is not so dependent upon fossil fuel. For the same reason, large cities that do not have a good agrarian base will become unsustainable and start to depopulate, at the very least.

” Like in medieval times, you might have to forbid living in cities unless born there, while encouraging people to be tied to the land in a real sense…”

With decentralizing, small towns with a concrete community and people will start vetting who is living there. They can admit those they think will be good prospects but ideally they would be transitioning to a political system where newcomers do not immediately have the right to participate in government until after they have proven themselves, if at all.

i’ve been hearing about peak oil since forever, and since then even more oil came in thanks to shale. yes, the reserves will peak some time, but i don’t tend to trust alarmists that tell you “the end is near” about this and other things (gold, petrodollar, credit bubble). of course there will be a big burst – but, only the Father knows the day and the time…

besides, the ones who truly worry are those countries without oil. which is why i rather not be like the Eurocentrics that dream of all whites returning to Europe to defend it. maybe (if New World white numbers die down that much!), but at least for some time that would also mean pretty much becoming subsidiaries of Russia for oil, abandoning Keystone XL, Australia, South African minerals, etc to the Chinese/Bindi/brown/(((them))) coalition. and you know these hypothetical Chinese-Semitic overlords would take a steaming one on the whitelib environmentalists, and use the oil profits to keep the colored waves coming on Europe anyway.

but yes, irregardless i think eventually agrarianism is coming, perhaps not due to fossil fuels running out but i think more because of the increasingly dystopian cities. think late Roman times. of course, heavy vetting will be implemented – although i also think nobility/warlords may also return as a result. but then again, that is why a dissolution of the Union gains in probability. and even then, there might not be enough fertile land in some areas, so landwars may return.

some degree of agrarianism will come back, i meant. because probably there will still be a lot of very fancy tech, if more individualized and personalized. thinking of self-sufficient regions sticking together, using oil profit money to give farmers good tractors and wifi with personal servers and better land; but otherwise leaving them independent and not subsuming them nor centralizing nor consumerizing; at most allowing local community organization (what Catholics call subsidiarity).